Macroeconomics Chapter 10: Economic Policies - Fiscal Policy

This chapter explores the concept of fiscal policy and its role in influencing the aggregate demand in the economy.

What fiscal policy is

Fiscal policy refers to decisions made by the government about its expenditure, taxation, and borrowing, and it represents one of the main tools through which the government seeks to influence the performance of the macroeconomy. Through fiscal policy, the government can affect the level of total spending in the economy, the distribution of income and wealth, and the allocation of resources between different uses. In the United States, fiscal policy decisions are primarily implemented through the federal budget process, with additional fiscal activity undertaken by state and local governments.

At its most basic level, fiscal policy concerns how much the government chooses to spend, how much it chooses to raise in tax revenue, and how any gap between the two is financed. Because government expenditure is itself a component of aggregate demand, changes in fiscal policy have direct implications for the overall level of economic activity. An increase in government spending or a reduction in taxation increases aggregate demand, while a decrease in government spending or an increase in taxation reduces aggregate demand. In this way, fiscal policy can be used to influence output, employment, and inflation.

Fiscal policy also plays a role in correcting forms of market failure. In situations where markets fail to allocate resources efficiently, the government may use taxation and expenditure to improve outcomes. For example, taxes can be used to discourage activities that generate negative external effects, while government spending can be used to provide goods and services that would otherwise be underprovided by the private sector. In addition, fiscal policy can be used to redistribute income, reducing inequalities that arise from market outcomes.

At the macroeconomic level, fiscal policy is closely linked to the government’s broader economic objectives. These typically include maintaining economic growth, achieving high levels of employment, promoting price stability, and ensuring a more equitable distribution of income. Decisions about fiscal policy therefore involve trade-offs, since measures designed to achieve one objective may conflict with others. For example, an expansionary fiscal policy aimed at reducing unemployment may place upward pressure on prices or increase government borrowing.

Fiscal policy differs from monetary policy in that it is implemented directly through government decisions on spending and taxation rather than through changes in interest rates or the money supply. Because fiscal policy involves political decision-making and legislative approval, it often operates with longer time lags than monetary policy. Once implemented, however, changes in fiscal policy can have a powerful effect on economic activity, particularly during periods of economic downturn or recession.

Overall, fiscal policy represents a central mechanism through which the government intervenes in the economy. By adjusting its spending and taxation, the government can influence aggregate demand, address market failures, and alter the distribution of income. The effectiveness of fiscal policy depends on the economic context in which it is used, the size and structure of the policy changes, and the way households and firms respond to those changes.

The government budget

Fiscal policy operates through the government budget, which records the relationship between government receipts and government expenditures over a given period of time. In the United States, this budget is set out annually through the federal budget process, with projections for revenues, spending, and borrowing that reflect the government’s fiscal priorities and policy objectives. The overall balance between receipts and outlays determines whether the government is running a budget surplus, a budget deficit, or a balanced budget.

Government receipts in the United States come mainly from taxation. The largest sources are individual income taxes, payroll taxes that fund Social Security and Medicare, and corporate income taxes. Additional revenue is raised through excise taxes, customs duties, and other fees and charges. The level of receipts depends not only on tax rates but also on the state of the economy, since tax revenues tend to rise during periods of economic growth and fall during recessions as incomes, profits, and spending decline.

Government expenditure covers a wide range of activities and can be divided into current expenditure and capital expenditure. Current expenditure refers to spending on goods and services that are used up within the current period. This includes spending on public services such as education, healthcare, defense, and public administration, as well as transfer payments. Transfer payments involve the redistribution of income rather than the direct purchase of goods and services, and in the United States they include programs such as Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, unemployment insurance, and income support programs.

Capital expenditure refers to government spending on long-lasting assets that contribute to future productive capacity. This includes spending on infrastructure such as highways, bridges, public transit systems, and government buildings, as well as investment in research and development. Such spending is intended to raise the economy’s long-run productive potential rather than to meet immediate consumption needs.

When government expenditure exceeds government receipts, the budget is in deficit. In this case, the government must borrow to finance the shortfall, typically by issuing Treasury securities. When receipts exceed expenditure, the budget is in surplus, allowing the government to reduce outstanding debt or accumulate financial assets. A balanced budget occurs when receipts and expenditure are equal, although this outcome is relatively rare in practice and is not always a policy objective in itself.

The size and direction of the government budget position have important macroeconomic implications. A higher level of government spending or lower taxation increases aggregate demand directly, while a reduction in spending or an increase in taxation reduces aggregate demand. As a result, changes in the budget position influence output, employment, and price levels. The government budget is therefore a key channel through which fiscal policy affects the overall performance of the economy.

In addition, the composition of government spending and taxation matters, not just the overall balance. Different forms of spending and taxation have different effects on incentives, income distribution, and economic efficiency. For this reason, fiscal policy analysis focuses not only on whether the budget is in deficit or surplus, but also on how government resources are raised and how they are used.

The government budget

Fiscal policy operates through the government budget, which records the relationship between government receipts and government expenditures over a given period of time. In the United States, this budget is set out annually through the federal budget process, with projections for revenues, spending, and borrowing that reflect the government’s fiscal priorities and policy objectives. The overall balance between receipts and outlays determines whether the government is running a budget surplus, a budget deficit, or a balanced budget.

Government receipts in the United States come mainly from taxation. The largest sources are individual income taxes, payroll taxes that fund Social Security and Medicare, and corporate income taxes. Additional revenue is raised through excise taxes, customs duties, and other fees and charges. The level of receipts depends not only on tax rates but also on the state of the economy, since tax revenues tend to rise during periods of economic growth and fall during recessions as incomes, profits, and spending decline.

Government expenditure covers a wide range of activities and can be divided into current expenditure and capital expenditure. Current expenditure refers to spending on goods and services that are used up within the current period. This includes spending on public services such as education, healthcare, defense, and public administration, as well as transfer payments. Transfer payments involve the redistribution of income rather than the direct purchase of goods and services, and in the United States they include programs such as Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, unemployment insurance, and income support programs.

Capital expenditure refers to government spending on long-lasting assets that contribute to future productive capacity. This includes spending on infrastructure such as highways, bridges, public transit systems, and government buildings, as well as investment in research and development. Such spending is intended to raise the economy’s long-run productive potential rather than to meet immediate consumption needs.

When government expenditure exceeds government receipts, the budget is in deficit. In this case, the government must borrow to finance the shortfall, typically by issuing Treasury securities. When receipts exceed expenditure, the budget is in surplus, allowing the government to reduce outstanding debt or accumulate financial assets. A balanced budget occurs when receipts and expenditure are equal, although this outcome is relatively rare in practice and is not always a policy objective in itself.

The size and direction of the government budget position have important macroeconomic implications. A higher level of government spending or lower taxation increases aggregate demand directly, while a reduction in spending or an increase in taxation reduces aggregate demand. As a result, changes in the budget position influence output, employment, and price levels. The government budget is therefore a key channel through which fiscal policy affects the overall performance of the economy.

In addition, the composition of government spending and taxation matters, not just the overall balance. Different forms of spending and taxation have different effects on incentives, income distribution, and economic efficiency. For this reason, fiscal policy analysis focuses not only on whether the budget is in deficit or surplus, but also on how government resources are raised and how they are used.

Cyclical and structural deficits

As the economy moves through the business cycle, the government budget position tends to change even if there are no deliberate changes to tax rates or spending programs. This is because government revenues and expenditures are closely linked to the level of economic activity. For this reason, economists distinguish between cyclical deficits and structural deficits when analysing fiscal policy.

A cyclical deficit is a budget deficit that arises because the economy is operating below its potential level of output. During a downturn or recession, national income falls and unemployment rises. As a result, tax revenues decline because households and firms earn less income and profits. At the same time, government spending on transfer payments such as unemployment benefits and income support increases. These changes widen the budget deficit automatically as part of the normal functioning of the fiscal system. When the economy recovers and returns toward trend growth, tax revenues rise and transfer payments fall, causing the cyclical deficit to shrink or disappear.

The key feature of a cyclical deficit is that it is temporary. It reflects short-run economic weakness rather than a fundamental imbalance between government spending commitments and revenue-raising capacity. For this reason, cyclical deficits are generally not viewed as a major long-term problem, provided that the economy is expected to recover. In fact, many economists see cyclical deficits as desirable because they help to stabilize aggregate demand by cushioning falls in income during downturns.

In contrast, a structural deficit exists when the government budget remains in deficit even when the economy is operating at or close to full employment. In this situation, government expenditure is persistently higher than government revenue at the economy’s potential level of output. A structural deficit indicates a long-term mismatch between spending plans and the tax base, rather than a temporary effect of the business cycle.

Structural deficits are more problematic than cyclical deficits because they imply ongoing borrowing regardless of economic conditions. If left unaddressed, a structural deficit will lead to a continual accumulation of government debt. Over time, rising debt levels increase interest payments, which themselves become a form of government expenditure. This can create a self-reinforcing process in which servicing existing debt makes it harder to reduce future deficits.

Distinguishing between cyclical and structural deficits is crucial for policy evaluation. A rising deficit during a recession may simply reflect cyclical weakness and may not require immediate corrective action. By contrast, a persistent deficit during periods of strong growth suggests a structural problem that may require changes to taxation, spending, or both. Policymakers therefore need to assess not just the size of the deficit, but also its underlying causes when designing fiscal strategy.

The national debt and government borrowing

When the government runs a budget deficit, it must borrow to finance the gap between its expenditure and its revenue. This borrowing adds to the national debt, which represents the total stock of outstanding government borrowing accumulated over time. In the United States, government borrowing is carried out primarily through the issuance of Treasury securities, such as Treasury bills, notes, and bonds, which are purchased by domestic and foreign investors.

The national debt is therefore a stock measure rather than a flow. It reflects the cumulative total of past budget deficits minus any surpluses that have been used to repay debt. Even if the government were to eliminate the budget deficit in a particular year, the national debt would remain unless a surplus were run and used to reduce it. For this reason, it is possible for the national debt to continue rising even when the annual deficit is falling.

Government borrowing allows the government to finance spending without raising taxes immediately. This can be particularly important during periods of economic weakness, when raising taxes or cutting spending would reduce aggregate demand further and worsen the downturn. By borrowing instead, the government can support economic activity while spreading the cost of spending over time.

However, government borrowing also has long-term implications. As the national debt grows, so do the interest payments required to service it. Interest payments represent a claim on future government revenue and therefore limit the resources available for other forms of public spending. In the United States, interest on the national debt constitutes a significant component of federal government expenditure.

The sustainability of the national debt depends on several factors. One key factor is the rate of economic growth. If the economy grows faster than the rate at which debt is accumulating, the debt burden relative to national income may remain stable or even fall over time. Conversely, if debt grows faster than the economy, the debt-to-income ratio will rise, increasing concerns about fiscal sustainability.

The interest rate at which the government borrows is also crucial. Lower interest rates reduce the cost of servicing debt and make higher levels of borrowing more manageable. Higher interest rates increase debt servicing costs and can place pressure on future budgets. Investor confidence in the government’s ability to manage its finances influences the interest rate it must pay on borrowed funds.

Government borrowing therefore involves a trade-off. Borrowing can support economic stability and long-run investment, but excessive or poorly managed borrowing can create future fiscal pressures. For this reason, analysis of the national debt focuses not only on its absolute size, but also on its relationship to national income, growth prospects, and interest rates.

Discretionary fiscal policy and automatic stabilisers

Fiscal policy can influence the economy in two distinct ways. Some changes in government spending and taxation occur automatically as the economy moves through the business cycle, while others result from deliberate policy decisions taken by the government. To analyse fiscal policy accurately, economists therefore distinguish between automatic stabilisers and discretionary fiscal policy.

Automatic stabilisers are features of the fiscal system that cause government spending and taxation to change automatically in response to changes in economic activity, without the need for new legislation or policy decisions. In the United States, the most important automatic stabilisers operate through the tax system and through transfer payments.

When the economy enters a downturn, household incomes and business profits tend to fall. As a result, tax revenues decline automatically because income taxes, payroll taxes, and corporate taxes are linked to earnings and profits. At the same time, government spending on transfer payments such as unemployment insurance, income support, and certain welfare programs increases as more individuals become eligible for assistance. These automatic changes increase the budget deficit and inject spending power into the economy, helping to soften the fall in aggregate demand.

Conversely, during periods of economic expansion, rising incomes and profits increase tax revenues automatically, while spending on unemployment-related benefits falls. This reduces the budget deficit or may even create a surplus, withdrawing spending power from the economy and helping to moderate excessive growth and inflationary pressure. In this way, automatic stabilisers dampen fluctuations in economic activity and reduce the severity of the business cycle.

A key advantage of automatic stabilisers is that they operate quickly and predictably. Because they are built into the fiscal system, they respond immediately to changes in economic conditions, avoiding the delays associated with policy formulation and legislative approval. They also provide a degree of macroeconomic stability without requiring constant government intervention.

Discretionary fiscal policy, by contrast, refers to deliberate changes in government spending or taxation undertaken in response to economic conditions or policy objectives. Examples include stimulus packages that increase government spending during a recession, tax cuts designed to boost consumption and investment, or spending reductions aimed at reducing a persistent structural deficit.

Discretionary fiscal policy allows governments to target specific economic problems more precisely than automatic stabilisers. For example, spending can be directed toward particular sectors or regions, or tax changes can be designed to influence specific groups of households or firms. However, discretionary policy is subject to several limitations. Decisions often involve political debate and legislative processes, which can delay implementation. By the time measures take effect, economic conditions may have changed.

There is also a risk that discretionary fiscal policy may be poorly timed or poorly calibrated. Expansionary measures introduced too late in the cycle may contribute to inflation rather than supporting growth. Similarly, contractionary measures introduced during a downturn may worsen unemployment and reduce output.

Automatic stabilisers and discretionary fiscal policy therefore play complementary roles. Automatic stabilisers provide a baseline level of economic stability, while discretionary policy allows governments to respond more actively when economic shocks are large or persistent. Understanding the distinction between the two is essential for evaluating the effectiveness and risks of fiscal intervention.

Fiscal policy and the AD–AS model

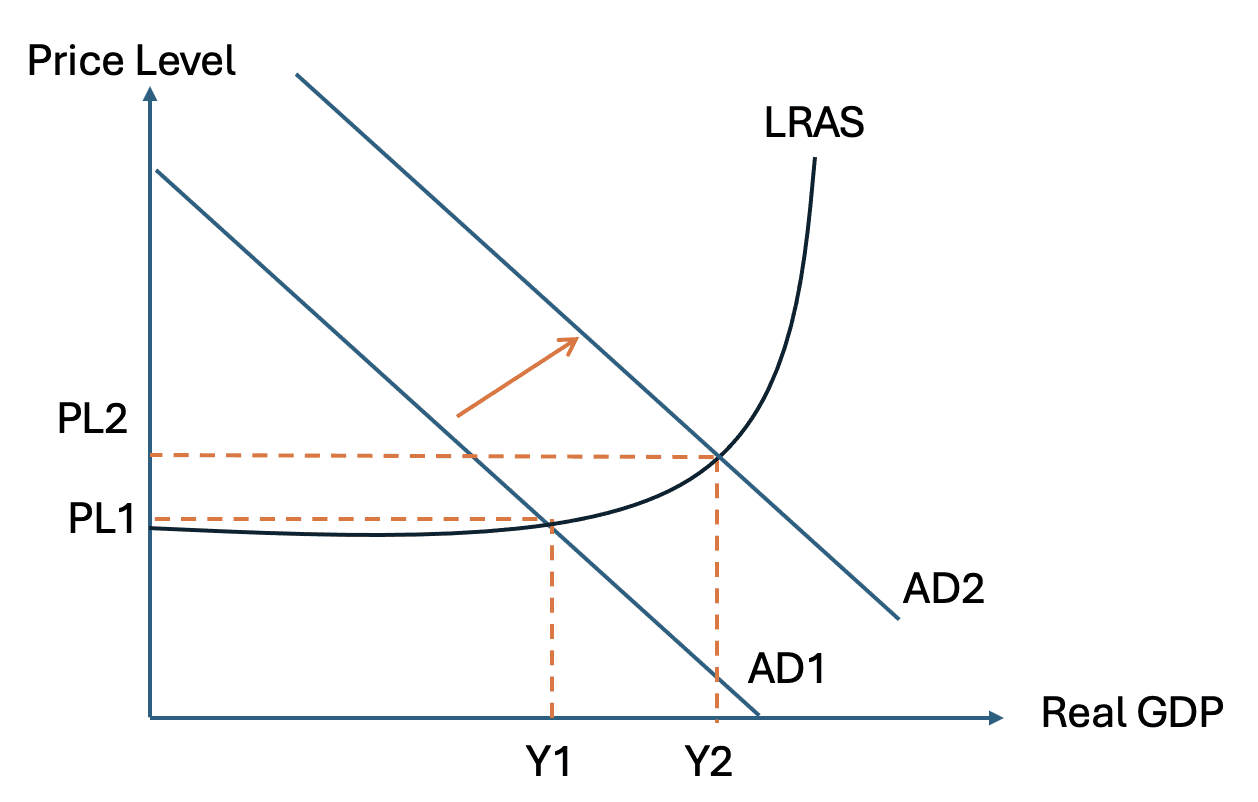

Fiscal policy can be analysed using the aggregate demand and aggregate supply model, which shows how changes in government spending and taxation affect the overall level of output and prices in the economy. Because government expenditure is a direct component of aggregate demand, fiscal policy operates primarily through shifts in the aggregate demand curve.

An expansionary fiscal policy involves an increase in government spending, a reduction in taxation, or a combination of both. An increase in government spending directly raises aggregate demand, shifting the aggregate demand curve to the right. A reduction in taxation increases households’ disposable income and firms’ post-tax profits, which encourages higher consumption and investment. This also shifts aggregate demand to the right. In both cases, the initial increase in spending is typically amplified by the multiplier process, as higher income leads to further rounds of consumption.

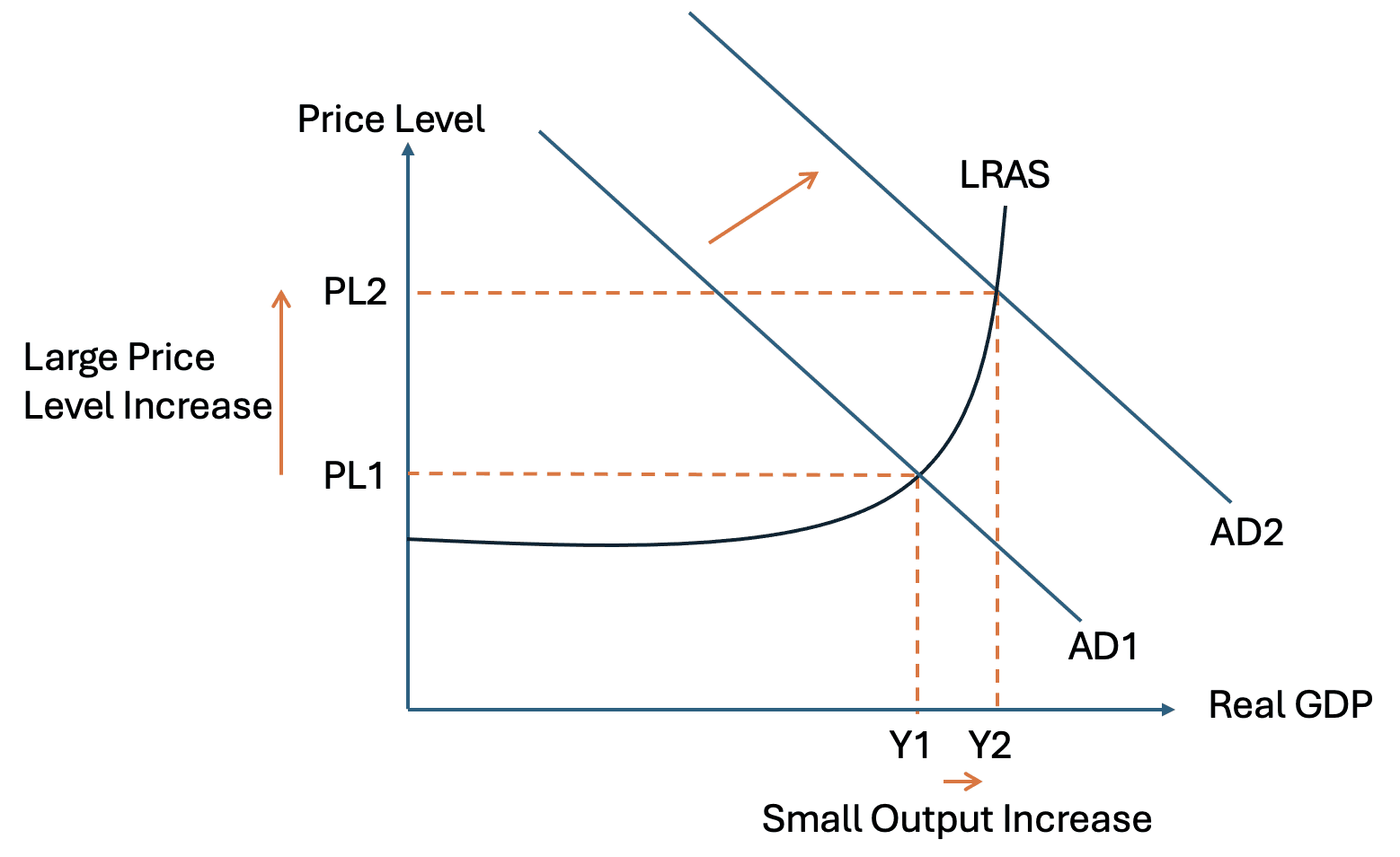

The effect of expansionary fiscal policy depends on the shape and position of the aggregate supply curves. In the short run, when spare capacity and unemployment exist, the short-run aggregate supply curve is upward sloping. A rightward shift of aggregate demand in this context leads to an increase in real output and employment, with some upward pressure on the price level. The increase in output reflects higher demand for goods and services, which encourages firms to raise production and hire more labour.

If the economy is operating close to full employment, the effects of expansionary fiscal policy differ. When output is near potential and the long-run aggregate supply curve is vertical, a rightward shift of aggregate demand mainly leads to an increase in the price level rather than an increase in real output. In this situation, fiscal expansion creates inflationary pressure rather than sustained growth in output.

Contractionary fiscal policy involves a reduction in government spending, an increase in taxation, or both. A decrease in government spending directly reduces aggregate demand, while higher taxes reduce disposable income and consumption. These changes shift the aggregate demand curve to the left. In the short run, this leads to a fall in real output and employment, along with downward pressure on the price level.

Contractionary fiscal policy may be used to reduce inflationary pressure when aggregate demand is growing too rapidly. By reducing spending in the economy, the government can help to bring demand back into line with productive capacity. However, if contractionary measures are applied during a period of weak demand, they may increase unemployment and slow economic growth.

The AD–AS framework highlights an important limitation of fiscal policy. Its effectiveness depends on the state of the economy. Expansionary fiscal policy is more likely to raise output and employment when spare capacity exists, while contractionary fiscal policy is more effective at controlling inflation when the economy is operating beyond potential output.

Using the AD–AS model also clarifies the potential trade-offs involved in fiscal policy. Policies designed to boost output and employment may generate inflation if applied at the wrong point in the business cycle. Similarly, policies aimed at price stability may reduce output and employment in the short run. For this reason, fiscal policy must be carefully calibrated to prevailing economic conditions.

Crowding out

Crowding out refers to the possibility that expansionary fiscal policy may reduce private sector spending, thereby offsetting some or all of its intended impact on aggregate demand. This effect arises because government spending financed by borrowing can influence interest rates and financial market conditions, affecting the behaviour of households and firms.

When the government runs a budget deficit, it must borrow to finance the gap between its spending and its revenue. In the United States, this borrowing typically takes the form of issuing Treasury securities. Increased government borrowing raises the demand for loanable funds in financial markets. If the supply of loanable funds does not increase by the same amount, this higher demand can put upward pressure on interest rates.

Higher interest rates make borrowing more expensive for the private sector. Firms facing higher borrowing costs may reduce investment spending, delaying or cancelling planned projects. Households may also reduce consumption of interest-sensitive goods, such as housing and durable goods, because higher interest rates increase the cost of mortgages and consumer credit. As a result, part of the increase in aggregate demand generated by higher government spending may be offset by lower private investment and consumption.

This process is known as financial crowding out. The extent to which it occurs depends on conditions in financial markets and the wider economy. If the economy is operating close to full employment and financial markets are tight, increased government borrowing is more likely to raise interest rates and crowd out private spending. In this case, the net effect of expansionary fiscal policy on aggregate demand may be limited.

Crowding out is less likely to be significant when the economy is operating below potential output and interest rates are low. During periods of weak demand or recession, there may be substantial spare capacity in financial markets. In such circumstances, increased government borrowing may not lead to higher interest rates because there is ample willingness to lend. Private investment may already be subdued due to weak demand expectations, so government spending may not displace much private activity.

There is also a distinction between short-run and long-run crowding out. In the short run, expansionary fiscal policy may raise output and employment when spare capacity exists. Over the longer run, persistent government borrowing may contribute to higher interest rates as debt accumulates, increasing the likelihood of crowding out private investment. Reduced investment can slow the growth of the capital stock, potentially lowering long-run economic growth.

Crowding out does not imply that expansionary fiscal policy is ineffective in all circumstances. Rather, it highlights that the impact of fiscal policy depends on how it is financed and on prevailing economic conditions. Policymakers must therefore consider the potential interaction between government borrowing, interest rates, and private sector behaviour when designing fiscal interventions.

Direct and indirect taxes

Taxes are a central component of fiscal policy because they determine how government revenue is raised and how the burden of financing public expenditure is distributed across households and firms. In economic analysis, taxes are commonly classified as direct taxes or indirect taxes, depending on how they are levied and who bears their initial legal responsibility.

Direct taxes are taxes that are levied directly on income or wealth and are paid straight to the government by the individual or organization on whom they are imposed. In the United States, the most important direct tax is the individual income tax. This tax is charged on earnings from employment, self-employment income, and certain forms of investment income. Corporate income tax is another form of direct tax, levied on the profits of firms. Taxes on property and wealth, such as property taxes, also fall into this category.

A key feature of direct taxes is that the taxpayer and the bearer of the tax are usually the same person or entity. For example, when an individual pays income tax, the legal responsibility for the tax and the reduction in disposable income fall on that individual. Because of this, direct taxes are often used as tools for redistribution. Progressive income tax systems, in which higher-income earners pay a higher proportion of their income in tax, reduce post-tax income inequality and play an important role in redistributive fiscal policy.

Indirect taxes are taxes that are levied on spending rather than on income or wealth. These taxes are included in the prices of goods and services and are collected by firms on behalf of the government. In the United States, examples of indirect taxes include sales taxes, excise taxes on specific goods such as gasoline, tobacco, and alcohol, and customs duties on imports.

With indirect taxes, the legal responsibility for paying the tax initially falls on firms, but the economic burden is often passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices. As a result, the final incidence of an indirect tax depends on market conditions, particularly the relative elasticities of demand and supply. If demand is relatively inelastic, consumers bear a larger share of the tax burden through higher prices. If demand is more elastic, producers may bear more of the burden through lower profit margins.

Direct and indirect taxes differ in their effects on income distribution. Direct taxes, especially when progressive, tend to reduce inequality by placing a greater burden on higher-income households. Indirect taxes are often regressive in nature because lower-income households tend to spend a larger proportion of their income on consumption. As a result, indirect taxes may take a larger share of income from poorer households than from richer ones, even if the tax rate is the same for all consumers.

From a macroeconomic perspective, taxes also influence aggregate demand. Increases in direct taxes reduce disposable income and may reduce consumption. Increases in indirect taxes raise prices and reduce real purchasing power, which can also lower consumption. Conversely, tax cuts increase disposable income and can stimulate spending, depending on households’ marginal propensity to consume.

The balance between direct and indirect taxation reflects government priorities and trade-offs. Direct taxes can support redistribution but may affect work and investment incentives. Indirect taxes are relatively easy to collect and generate stable revenue but may worsen income inequality. Fiscal policy involves choosing a mix of taxes that raises sufficient revenue while supporting economic objectives such as efficiency, equity, and stability.

The Laffer curve

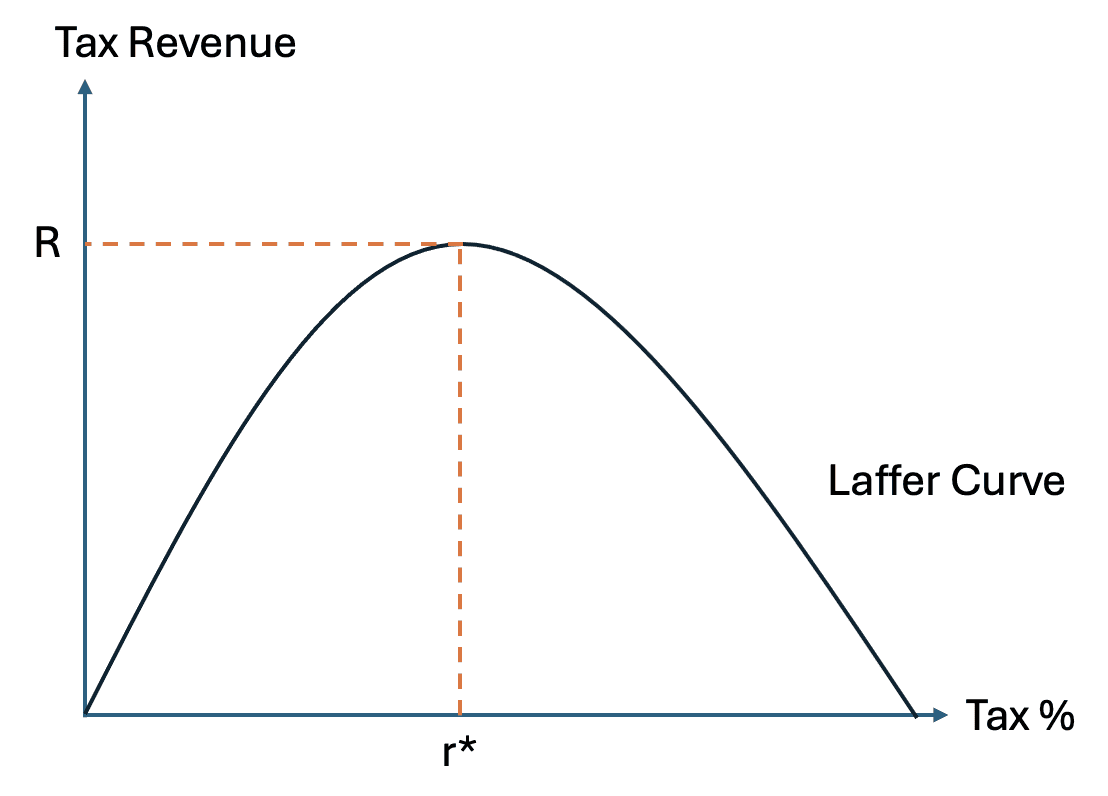

The Laffer curve illustrates the relationship between tax rates and the total tax revenue collected by the government. It is used to analyse how changes in tax rates may affect government revenue by influencing economic incentives and behaviour. The curve does not specify an exact tax rate that maximises revenue, but it highlights that tax revenue does not necessarily rise proportionally with increases in tax rates.

At a tax rate of zero, government tax revenue is also zero because no tax is collected. At the other extreme, at a tax rate of one hundred percent, tax revenue is also assumed to be zero because individuals and firms would have no incentive to work, save, invest, or report income if all earnings were taxed away. Under these conditions, economic activity would fall sharply, and the tax base would collapse.

Between these two extremes, tax revenue rises as tax rates increase, up to a certain point. At low tax rates, increases in the tax rate raise revenue because the disincentive effects on work and investment are relatively small. Most individuals continue to supply labour and firms continue to invest, so the tax base remains large. In this range, higher tax rates lead to higher tax revenue.

Beyond a certain tax rate, however, further increases may reduce total tax revenue. At high tax rates, individuals may choose to work fewer hours, retire earlier, or reduce effort because the reward from working is lower. Firms may reduce investment or shift activity to lower-tax jurisdictions. In addition, higher tax rates may encourage tax avoidance or evasion. These behavioural responses reduce the size of the tax base, potentially causing total tax revenue to fall even as the tax rate rises.

The Laffer curve is therefore based on the idea that taxes influence incentives and economic behaviour. The precise shape of the curve and the location of the revenue-maximising tax rate depend on factors such as labour supply responsiveness, the ease of tax avoidance, and the structure of the tax system. These factors differ across countries and over time, making it difficult to identify the exact position of an economy on the curve.

The Laffer curve is often used in debates about fiscal policy and taxation. Supporters of tax cuts may argue that existing tax rates are high enough that reducing them could increase economic activity and potentially raise tax revenue. Critics argue that in many cases tax rates are below the revenue-maximising level, so tax cuts would reduce government revenue and increase budget deficits.

From an economic perspective, the Laffer curve does not imply that lower taxes always raise revenue. Instead, it highlights the trade-off between tax rates, incentives, and revenue. Policymakers must consider not only how tax rates affect government finances, but also how they influence work, investment, and economic growth.

Influencing income distribution

Fiscal policy plays a central role in shaping the distribution of income within the economy. Through the combined effects of taxation and government spending, the government can alter the distribution of disposable income relative to the distribution that emerges from market forces alone. In the United States, fiscal policy is one of the main mechanisms used to reduce income inequality and alleviate poverty.

Taxation influences income distribution primarily through the structure of the tax system. Progressive income taxes reduce inequality by taking a larger proportion of income from higher earners than from lower earners. As a result, post-tax income differences are smaller than pre-tax income differences. In the United States, the federal income tax system is progressive, with higher marginal tax rates applied to higher income brackets. This progressivity means that fiscal policy directly redistributes income from higher-income households toward the funding of public services and transfer payments.

Indirect taxes, by contrast, tend to have a different effect on income distribution. Sales taxes and excise taxes apply at the same rate regardless of income, but lower-income households typically spend a larger proportion of their income on consumption. This means that indirect taxes often take a higher proportion of income from poorer households than from richer households, making them regressive in effect. The overall impact of fiscal policy on income distribution therefore depends on the balance between direct and indirect taxation.

Government spending is equally important in influencing income distribution. Transfer payments play a direct redistributive role by providing income to households with low or no earnings. In the United States, programs such as Social Security, unemployment insurance, and income support transfers increase the disposable income of retirees, unemployed workers, and low-income households. These payments reduce poverty and narrow income gaps.

Public spending on services also affects income distribution indirectly. Spending on education improves access to skills and qualifications, raising earning potential over time. Public healthcare spending reduces the financial burden of medical costs, particularly for low-income households. By providing these services collectively rather than through the market, the government reduces the extent to which access depends on income.

The effectiveness of fiscal policy in influencing income distribution depends on how policies are designed and targeted. Well-targeted transfers and progressive taxes can significantly reduce inequality, while poorly targeted spending or reliance on regressive taxes may limit redistributive effects. Policymakers must also consider incentive effects, since very high taxes or poorly structured benefits may reduce incentives to work or invest.

Fiscal policy therefore shapes income distribution through both sides of the government budget. By altering how income is taxed and how public resources are spent, the government can influence not only current living standards but also long-run opportunities and economic mobility.

The effectiveness of fiscal policy

The effectiveness of fiscal policy depends on how strongly changes in government spending and taxation influence aggregate demand, output, employment, and prices. While fiscal policy has the potential to play a powerful stabilising role in the economy, its impact is subject to a number of limitations and uncertainties that affect how reliable it is as a macroeconomic tool.

One key factor influencing the effectiveness of fiscal policy is the size of the multiplier. The multiplier measures the extent to which an initial change in government spending or taxation leads to a larger final change in national income. If households have a high marginal propensity to consume, an increase in government spending or a tax cut will generate multiple rounds of additional spending, making fiscal policy more effective. If households save a large proportion of additional income, the multiplier will be smaller and the impact on output will be weaker.

Time lags represent a major limitation of discretionary fiscal policy. There is often a delay between the emergence of an economic problem and the recognition that policy action is needed. Once action is proposed, further delays arise from political debate, legislative approval, and the practical implementation of spending programs or tax changes. By the time fiscal measures take effect, economic conditions may have changed, reducing the effectiveness of the intervention or even making it counterproductive.

Forecasting difficulties also reduce the reliability of fiscal policy. Policymakers must base decisions on estimates of the size of output gaps, potential growth, and future economic conditions. These estimates are uncertain and subject to revision. If the size of an economic downturn or expansion is misjudged, fiscal policy may be too weak to have a meaningful effect or too strong, creating inflationary pressure.

Crowding out further complicates the effectiveness of fiscal policy. As discussed earlier, increased government borrowing may raise interest rates and reduce private investment and consumption. If crowding out is significant, the net impact of expansionary fiscal policy on aggregate demand may be limited. This effect is more likely when the economy is close to full employment and financial markets are tight.

The state of the economy plays a crucial role in determining fiscal policy effectiveness. Expansionary fiscal policy tends to be more effective during periods of recession or when there is substantial spare capacity. In these conditions, additional demand is more likely to translate into higher output and employment rather than higher prices. By contrast, when the economy is operating near potential output, fiscal expansion is more likely to generate inflation than real growth.

Public confidence and expectations also matter. If households expect future tax increases to pay for current deficits, they may increase saving rather than spending, reducing the impact of fiscal stimulus. Similarly, firms may delay investment if they are uncertain about future fiscal conditions. These behavioural responses can weaken the transmission of fiscal policy.

Despite these limitations, fiscal policy remains an important tool, particularly in situations where monetary policy is constrained or less effective. Automatic stabilisers provide a reliable baseline level of economic support, while discretionary fiscal measures can play a critical role in responding to large economic shocks. The effectiveness of fiscal policy therefore depends on timing, scale, economic context, and policy design rather than on fiscal intervention alone.

Fiscal policy and macroeconomic objectives

Fiscal policy is closely linked to the government’s broader macroeconomic objectives. By influencing aggregate demand, income distribution, and resource allocation, fiscal policy can contribute to economic growth, price stability, full employment, and a more equitable distribution of income.

In terms of economic growth, government spending on infrastructure, education, and research can raise the economy’s productive capacity over time. Well-targeted capital expenditure improves productivity and supports long-run growth. At the same time, excessive borrowing that crowds out private investment may reduce growth potential, highlighting the need for balance.

Fiscal policy also plays a role in promoting price stability. Contractionary fiscal measures can reduce inflationary pressure when aggregate demand is growing too rapidly. Conversely, expansionary fiscal policy can help prevent deflation during periods of weak demand. The impact on prices depends on the economy’s position relative to potential output.

Full employment is another central objective. Expansionary fiscal policy can raise aggregate demand and increase labour demand during downturns, reducing cyclical unemployment. Public spending programs and tax measures can support job creation directly and indirectly, particularly when private sector demand is weak.

Fiscal policy also affects the distribution of income. Progressive taxation and transfer payments reduce post-tax income inequality and alleviate poverty. Public spending on education, healthcare, and social support improves welfare and expands access to opportunities, contributing to greater economic inclusion.

Finally, fiscal policy must be consistent with long-run fiscal sustainability. Persistent structural deficits and rising debt may limit future policy options and increase interest burdens. Achieving macroeconomic objectives therefore requires balancing short-run stabilisation with long-run fiscal responsibility.