Macroeconomics Chapter 15: Exchange Rates

This chapter explores the concepts of exchange rates and exchange rate systems.

Introduction to exchange rates

Exchange rates play a central role in the macroeconomy because they determine the rate at which one currency is exchanged for another. In the United States, the exchange rate of the dollar against other currencies affects the competitiveness of U.S. firms in international markets, the prices paid by American consumers for imported goods and services, and the returns earned by foreign investors who hold dollar-denominated assets. Exchange rates are also closely connected to the balance of payments and therefore to the broader performance and stability of the economy.

The way in which an exchange rate is determined has wide-ranging consequences for macroeconomic policy. Some systems allow the exchange rate to be determined entirely by market forces, while others involve direct government intervention to manage or fix the value of the currency. Understanding how exchange rates are determined, why they change, and how different exchange rate systems operate is therefore essential for understanding how open economies function.

The exchange rate

The exchange rate is defined as the price of one currency in terms of another. For the United States, this may be expressed as the number of U.S. dollars required to buy one unit of a foreign currency, or alternatively as the number of foreign currency units that can be bought with one dollar. The exchange rate matters because it influences both international trade and international financial flows.

Whenever Americans purchase goods, services, or assets from abroad, they must exchange dollars for foreign currency. This creates a demand for foreign currency and, at the same time, a supply of dollars in the foreign exchange market. Conversely, when foreign residents purchase U.S. goods, services, or assets, they must exchange their own currency for dollars, creating a demand for dollars. In this way, international transactions generate demand and supply for currencies.

Foreign exchange transactions are therefore an integral part of international trade and investment. Imports, exports, tourism, foreign direct investment, and portfolio investment all involve currency exchange. The balance of payments records these transactions and reflects the overall demand for and supply of a country’s currency.

The demand for a currency is a derived demand. Dollars are not demanded for their own sake, but because they are required to purchase U.S. goods, services, or assets. Similarly, the supply of dollars arises when U.S. residents wish to buy foreign goods, services, or assets and must exchange dollars for another currency.

The foreign exchange market

The foreign exchange market can be analyzed using the familiar framework of demand and supply. Consider the market for U.S. dollars. On a diagram, the vertical axis measures the exchange rate, expressed as dollars per unit of foreign currency, and the horizontal axis measures the quantity of dollars exchanged per period.

The demand curve for dollars slopes downward. When the dollar is relatively weak, meaning that fewer dollars are required to purchase a unit of foreign currency, U.S. goods and services are relatively cheap for foreign buyers. As a result, foreigners are more willing to purchase U.S. exports and assets, increasing the demand for dollars. When the dollar is relatively strong, U.S. goods and services become more expensive for foreign buyers, reducing the demand for dollars.

The supply curve of dollars slopes upward. When the dollar is relatively strong, foreign goods and services are relatively cheap for U.S. residents. This encourages imports and overseas investment, increasing the supply of dollars on the foreign exchange market. When the dollar is relatively weak, foreign goods and services become more expensive for Americans, reducing imports and lowering the supply of dollars.

The equilibrium exchange rate occurs where the demand for dollars equals the supply of dollars. At this exchange rate, the quantity of dollars demanded by foreigners exactly matches the quantity supplied by U.S. residents. This equilibrium has an important connection to the balance of payments. When the foreign exchange market is in equilibrium, the overall balance of payments is in balance, meaning that total inflows and outflows of dollars are equal.

Exchange rates and international competitiveness

The exchange rate plays a crucial role in determining the competitiveness of domestic firms. A depreciation of the dollar makes U.S. exports cheaper for foreign buyers and imports more expensive for American consumers. This tends to increase exports and reduce imports, improving the trade balance, other things being equal. An appreciation of the dollar has the opposite effect, making exports more expensive and imports cheaper, which can reduce the competitiveness of U.S. firms.

Because of this, changes in the exchange rate can have significant effects on output, employment, and inflation. A weaker dollar may stimulate aggregate demand by boosting net exports, while a stronger dollar may dampen demand by encouraging imports. These effects link exchange rates closely to macroeconomic policy objectives such as economic growth, price stability, and external balance.

Fixed exchange rate systems

One way in which an exchange rate can be determined is through a fixed exchange rate system. Under a fixed exchange rate system, the government commits to maintaining the value of its currency at a specified rate against another currency or a basket of currencies. The exchange rate is therefore set by policy rather than by free market forces.

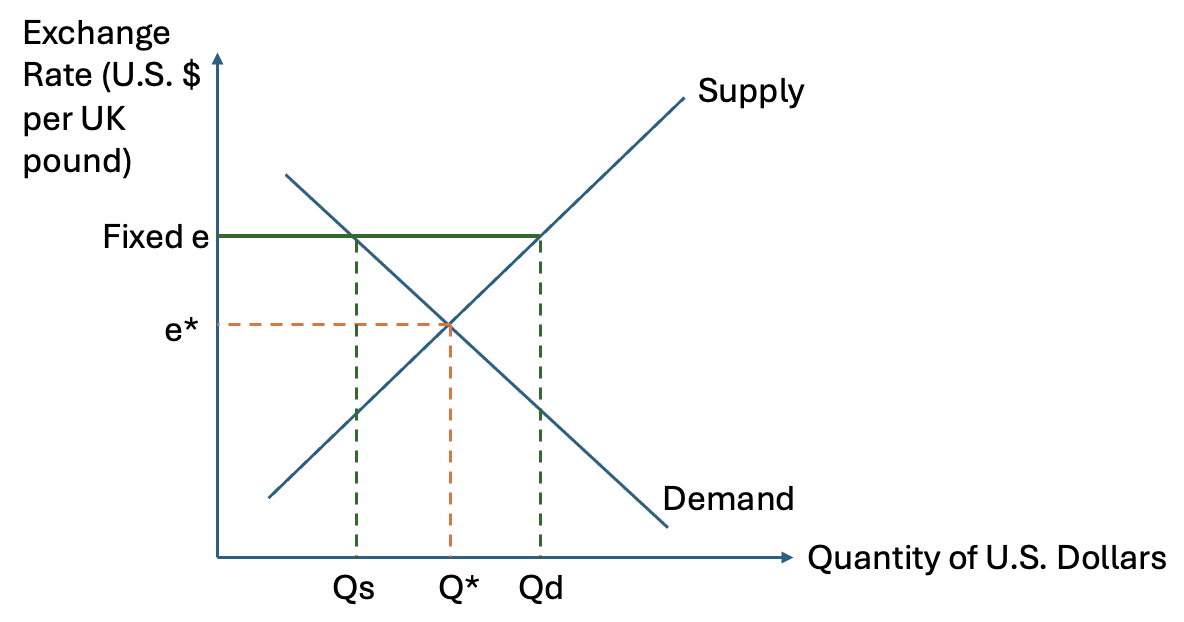

In a fixed exchange rate system, the authorities must intervene in the foreign exchange market to maintain the chosen rate. If the demand for dollars exceeds the supply at the fixed rate, upward pressure will arise that would normally cause the dollar to appreciate. To prevent this, the authorities must supply additional dollars, often by purchasing foreign currency assets. If the supply of dollars exceeds demand, downward pressure will arise that would normally cause the dollar to depreciate. In this case, the authorities must buy dollars using foreign exchange reserves.

Foreign exchange reserves are stocks of foreign currency and gold held by the central bank. These reserves allow the authorities to intervene in the foreign exchange market to offset imbalances between demand and supply at the fixed exchange rate. However, reserves are finite, and persistent imbalances can place severe strain on the system.

A fixed exchange rate system can operate successfully only if the chosen exchange rate is close to the long run equilibrium level. If the currency is persistently overvalued or undervalued, the authorities will be forced to intervene repeatedly, leading to the accumulation or depletion of reserves. In such cases, the system may become unsustainable.

If a country experiences a persistent deficit in its balance of payments under a fixed exchange rate system, it may eventually be forced to reduce the value of its currency. This is known as a devaluation, which refers to a deliberate downward adjustment of the exchange rate by the authorities. Conversely, a revaluation is a deliberate upward adjustment of the exchange rate.

The breakdown of fixed exchange rate systems

Historically, fixed exchange rate systems have often struggled to survive in the long run. One important example is the Bretton Woods system, established after the Second World War. Under this system, many countries agreed to fix their currencies to the U.S. dollar, while the dollar itself was linked to gold.

Over time, differences in inflation rates and economic conditions made it increasingly difficult to maintain fixed exchange rates. As the supply of dollars expanded, confidence in the system weakened, and countries found it harder to defend their exchange rate pegs. Eventually, the system collapsed, and most major economies moved toward floating exchange rates.

Floating exchange rate systems

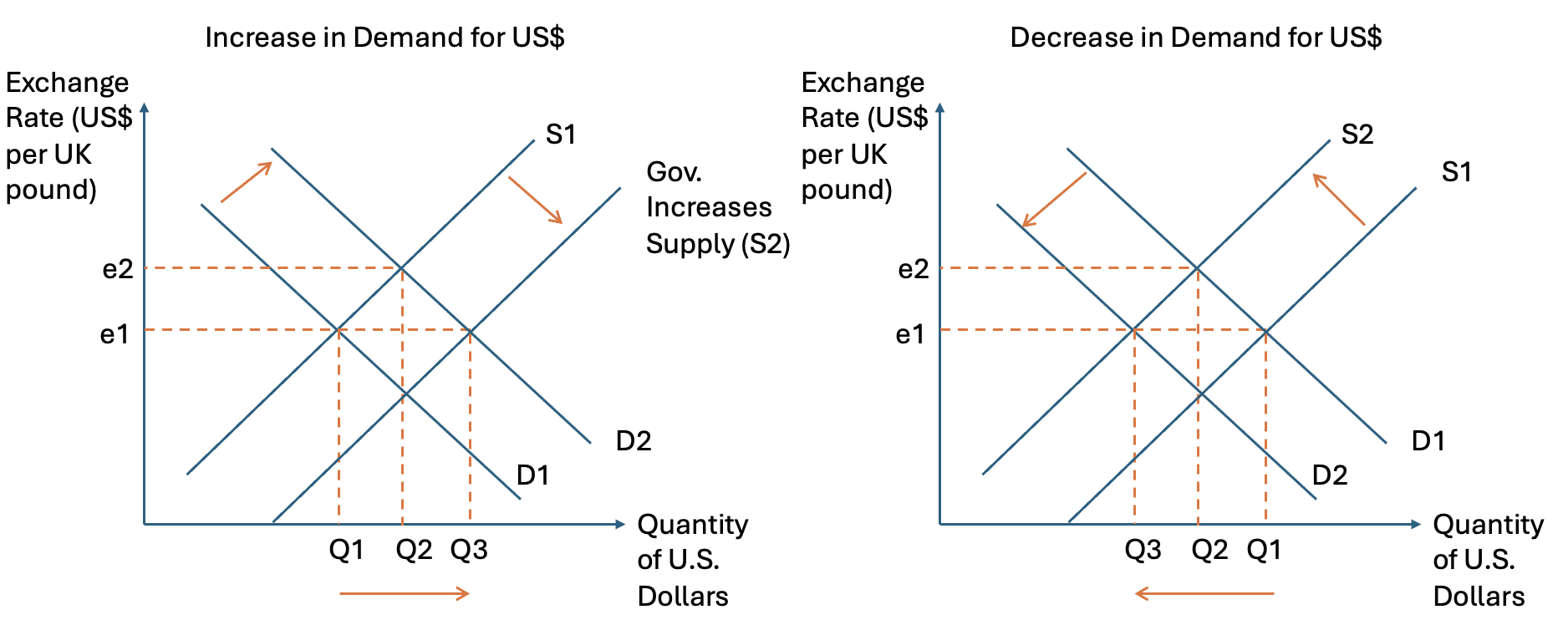

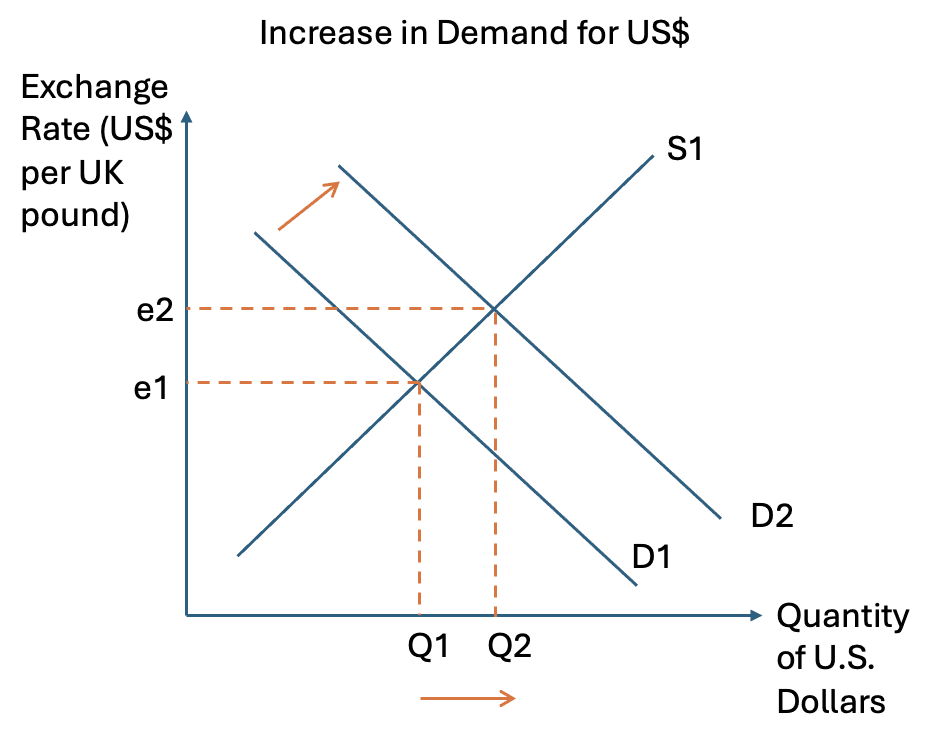

Under a floating exchange rate system, the value of the currency is determined by market forces of demand and supply, with little or no direct government intervention. The exchange rate is free to adjust in response to changes in economic conditions.

In a floating system, if the demand for dollars increases, the exchange rate will rise, causing the dollar to appreciate. If demand falls or supply rises, the exchange rate will fall, leading to a depreciation. These movements help to restore equilibrium in the foreign exchange market and in the balance of payments.

One important implication of a floating exchange rate system is that the overall balance of payments is automatically balanced over time. Changes in the exchange rate adjust relative prices and incentives, influencing exports, imports, and capital flows in a way that restores equilibrium.

However, floating exchange rates can be volatile. Short run movements in the exchange rate may be influenced by speculation, changes in investor sentiment, or shifts in expectations. As a result, the exchange rate may deviate from its long run equilibrium level for extended periods.

Causes of changes in exchange rates

Several factors can cause exchange rates to change under a floating exchange rate system. Differences in inflation rates between countries are particularly important. If inflation in the United States is higher than in its trading partners, U.S. goods become less competitive over time, reducing demand for dollars and placing downward pressure on the exchange rate.

The trade balance also matters. An increase in exports raises demand for dollars, while an increase in imports raises the supply of dollars. Changes in net exports therefore influence the exchange rate.

International capital flows play a major role as well. Foreign direct investment and portfolio investment affect the demand for and supply of currencies. If the United States becomes more attractive to foreign investors, demand for dollars will rise, leading to an appreciation.

Speculation can also influence exchange rates, particularly in the short run. If investors expect the dollar to appreciate in the future, they may buy dollars in anticipation of capital gains, pushing the exchange rate up in the present. If expectations reverse, capital may flow out rapidly, causing sharp movements in the exchange rate.

Interest rates and monetary policy are closely linked to exchange rate movements. Higher interest rates in the United States relative to other countries may attract capital inflows, increasing demand for dollars. However, expectations about future exchange rate movements also matter, as investors consider both interest returns and potential currency gains or losses.

Evaluation of exchange rate systems

Both fixed and floating exchange rate systems have strengths and weaknesses. A fixed exchange rate system can provide stability and reduce uncertainty for firms engaged in international trade. However, it requires large foreign exchange reserves and limits the independence of monetary policy, as interest rates may need to be adjusted to defend the exchange rate.

A floating exchange rate system allows greater flexibility and enables monetary policy to focus on domestic objectives such as price stability and employment. It also allows the exchange rate to adjust automatically to external shocks. However, floating rates can be volatile, increasing uncertainty for exporters and importers.

Consequences of exchange rate changes

Changes in the exchange rate can have far-reaching effects on the economy. An appreciation of the dollar tends to reduce inflation by lowering the price of imports, but it may also reduce export competitiveness and slow economic growth. A depreciation tends to boost exports and output, but it may increase inflation by raising import prices.

Because exchange rate movements affect many aspects of economic performance, they pose challenges for policymakers. Attempts to manage the exchange rate must be balanced against other macroeconomic objectives, and poorly designed policies can create instability rather than reduce it.

Evaluation of different exchange rate systems

When comparing fixed and floating exchange rate systems, the key issue is how each system copes with shocks and how it constrains or enables macroeconomic policy. Every open economy is exposed to external disturbances that originate outside its control, such as changes in global demand, shifts in commodity prices, financial crises, or changes in international interest rates. An exchange rate system must therefore be judged partly on how effectively it allows the economy to return to equilibrium after such shocks.

Under a floating exchange rate system, adjustment to external shocks occurs primarily through changes in the exchange rate itself. If the United States experiences a loss of competitiveness because inflation rises faster than in trading partner countries, the dollar will tend to depreciate. This depreciation lowers the foreign currency price of U.S. exports and raises the dollar price of imports, encouraging a shift toward domestically produced goods and helping to restore external balance. In this way, the exchange rate acts as a shock absorber, allowing relative prices to adjust without requiring large changes in output or employment.

By contrast, under a fixed exchange rate system, the exchange rate cannot adjust freely. If competitiveness deteriorates, the burden of adjustment must fall on the domestic economy instead. This may require tighter monetary policy, lower domestic demand, and slower growth in order to reduce imports and restore balance. As a result, adjustment under a fixed exchange rate system may involve higher unemployment and lower economic growth, at least in the short run.

Stability is another important criterion. Fixed exchange rate systems offer a high degree of certainty about future exchange rates. Firms engaged in international trade can plan investment and production decisions without worrying about currency fluctuations. This reduction in exchange rate risk may encourage trade and cross border investment. In contrast, floating exchange rates can be volatile, creating uncertainty for exporters and importers whose revenues and costs are denominated in different currencies.

However, stability under a fixed exchange rate system depends on the credibility of the commitment to maintain the exchange rate. If markets believe that the exchange rate is unsustainable, speculative pressures may build up, making the system increasingly fragile. Once confidence is lost, defending the exchange rate can become extremely costly and may ultimately fail.

Monetary policy independence is also a central consideration. Under a floating exchange rate system, the Federal Reserve can set interest rates to pursue domestic objectives such as controlling inflation or stabilizing output. Exchange rate movements are allowed to adjust in response to these policy decisions. Under a fixed exchange rate system, monetary policy must be directed toward maintaining the exchange rate target. Interest rates may need to be adjusted to attract or deter capital flows, even if this conflicts with domestic economic conditions.

Stability and credibility

A fixed exchange rate system can impose discipline on policymakers by limiting their ability to pursue expansionary policies that generate inflation. Because inflation would undermine the fixed exchange rate, governments may be forced to adopt more cautious fiscal and monetary policies. This discipline can enhance credibility, particularly in economies with a history of high inflation.

However, this discipline comes at a cost. If economic conditions require policy flexibility, a fixed exchange rate system may prevent an appropriate response. In such cases, the attempt to maintain the exchange rate can worsen economic outcomes rather than improve them.

Floating exchange rate systems avoid this problem by allowing policy to respond to domestic needs. However, critics argue that this flexibility may encourage irresponsible policy, as governments may rely on exchange rate depreciation to offset the effects of inflationary policies. In this sense, a floating exchange rate system may weaken external discipline.

Appreciation and depreciation under floating exchange rates

Under a floating exchange rate system, movements in the exchange rate take the form of appreciation or depreciation. An appreciation refers to a rise in the value of the currency, meaning that fewer units of domestic currency are required to purchase a unit of foreign currency. A depreciation refers to a fall in the value of the currency.

An appreciation of the dollar makes imports cheaper and exports more expensive. This can help reduce inflation by lowering import prices, but it may also weaken the competitiveness of U.S. firms and reduce net exports. A depreciation has the opposite effects, boosting export competitiveness but raising import prices and contributing to inflationary pressure.

Because these effects operate through prices, changes in the exchange rate influence both aggregate demand and aggregate supply. This explains why exchange rate movements are an important transmission mechanism through which macroeconomic shocks affect the economy.

Speculation and short run volatility

In the short run, exchange rates may deviate significantly from their long run equilibrium values. One reason for this is speculation. Investors may move large volumes of capital across borders in response to changes in interest rates, expectations about future exchange rates, or shifts in confidence. These capital flows, often described as hot money, can cause rapid and substantial movements in exchange rates.

Such movements may become self reinforcing. If investors expect the dollar to depreciate, they may sell dollar denominated assets, increasing the supply of dollars and pushing the exchange rate down. The depreciation then appears to confirm expectations, encouraging further capital outflows. Similar processes can operate in the opposite direction during periods of appreciation.

While speculation can help move exchange rates toward their long run equilibrium, it can also increase volatility and create uncertainty. This volatility can discourage trade and investment, particularly for firms that lack access to sophisticated financial hedging instruments.

Exchange rate changes and macroeconomic outcomes

Changes in exchange rates have broad macroeconomic consequences. They affect inflation through import prices, influence output and employment through net exports, and alter income distribution by changing relative prices between tradable and non tradable goods. Exchange rate movements can also affect financial stability, particularly when firms or governments hold debt denominated in foreign currency.

Because of these wide ranging effects, exchange rate policy cannot be considered in isolation. It interacts closely with fiscal policy, monetary policy, and broader macroeconomic objectives. Attempts to stabilize the exchange rate may conflict with goals such as low inflation or full employment, while allowing the exchange rate to float may create challenges for price stability and external competitiveness.

Overall assessment

There are strengths and weaknesses in both fixed and floating exchange rate systems. Floating exchange rates provide flexibility and allow economies to adjust to external shocks through price changes rather than changes in output and employment. They also preserve monetary policy independence. However, they can be volatile and may discourage international trade.

Fixed exchange rate systems offer stability and predictability, which can support trade and investment. They may also impose discipline on policymakers. However, they limit policy flexibility and can become unsustainable if economic conditions diverge from those implied by the fixed exchange rate.

The choice of exchange rate system therefore involves trade offs. No system is universally superior. The appropriate regime depends on the structure of the economy, the credibility of institutions, and the nature of the shocks the economy is likely to face.