Macroeconomics Chapter 16: Globalization

This chapter explores the concept of globalization and its impact on trade.

Globalization

Globalization refers to the process through which the world’s economies have become increasingly integrated. This integration occurs as a result of technological change, policy decisions, and the expansion of markets across national boundaries. As economies become more closely connected, events in one part of the world have stronger and more immediate effects on economic activity elsewhere. Production, trade, finance, information, and labor markets are no longer confined within national borders to the extent they once were.

At its core, globalisation involves the growing interdependence of countries. Firms increasingly operate across multiple countries, consumers purchase goods and services produced far from where they live, and financial capital moves rapidly between economies. This process has accelerated in recent decades, but it is not entirely new. What distinguishes the modern phase of globalisation is the speed, scale, and depth of economic integration made possible by advances in technology and by deliberate reductions in barriers to trade and capital flows.

Globalisation has generated substantial debate. Supporters emphasize its role in raising productivity, expanding consumer choice, and supporting economic growth. Critics focus on its distributional consequences, its environmental impact, and the vulnerability that comes from deeper economic interdependence. Understanding globalization therefore requires careful analysis of both its causes and its consequences.

Causes of globalization

Transportation and communication costs

One of the most important drivers of globalisation has been the dramatic reduction in transportation and communication costs. Advances in transportation technology have made it cheaper, faster, and more reliable to move goods across long distances. Improvements in shipping, logistics, and air freight have enabled firms to organize production on a global scale rather than being constrained to a single location.

Lower transportation costs have allowed firms to fragment the production process. Different stages of production can be located in different countries depending on cost conditions, skills, and resource availability. Labor intensive stages may be located where labor is relatively abundant and wages are lower, while capital intensive or high skill stages may remain in countries with advanced infrastructure and skilled workforces. This fragmentation has expanded international trade not only in final goods but also in intermediate components.

At the same time, advances in communication technology have transformed how firms operate. The growth of the internet, digital platforms, and real time communication tools has made it possible for firms to coordinate complex activities across borders with minimal delay. Information can be transmitted almost instantly, allowing firms to manage supply chains, monitor production, and respond to market changes on a global scale. These developments have reduced the importance of physical distance and made international operations far more feasible.

The spread of digital communication has also facilitated the exchange of knowledge and ideas. Firms can adopt new technologies more quickly, consumers become aware of new products, and services such as finance, consulting, and software development can be provided across borders. This has deepened global integration beyond trade in physical goods alone.

Reduction of trade barriers

A second major cause of globalisation has been the systematic reduction of barriers to international trade. Since the end of the Second World War, there has been a sustained effort to lower tariffs and other restrictions on trade in goods and services. These efforts were initially coordinated through the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, which organized successive rounds of tariff reductions. This role was later taken over by the World Trade Organization, which continues to oversee rules governing international trade.

Lower tariffs reduce the cost of imported goods and make it easier for firms to access foreign markets. As trade barriers fall, countries tend to trade more, leading to greater economic integration. In addition to tariff reductions, the removal of quotas, simplification of customs procedures, and harmonization of standards have further reduced obstacles to trade.

Regional trade agreements have also played an important role. Free trade areas and customs unions have been established in various parts of the world, encouraging trade between member countries by eliminating internal trade barriers. These arrangements have increased trade flows and encouraged firms to operate across national boundaries within these regions.

The reduction of trade barriers has been reinforced by policy choices aimed at promoting export led growth. Many countries have adopted strategies that encourage firms to compete in global markets, recognizing that access to larger markets can support economies of scale and productivity growth.

Deregulation of financial markets

Globalisation has also been driven by the deregulation of financial markets and the liberalization of capital flows. Restrictions on the movement of financial capital between countries have been reduced or removed in many economies. This has made it easier for firms to invest abroad, for financial institutions to operate internationally, and for investors to allocate funds across borders.

Advances in financial technology have reinforced this process by enabling rapid and large scale financial transactions. Capital can move quickly in response to changes in interest rates, expected returns, or economic conditions. This has increased the integration of global financial markets and strengthened the links between national economies.

The freer movement of capital has supported globalisation by financing international trade, enabling foreign direct investment, and facilitating the expansion of multinational corporations. However, it has also increased the potential for financial instability, as shocks can spread rapidly from one country to another.

Migration

Migration has contributed to globalisation by increasing the movement of labor across borders. Changes in policy, economic conditions, and political events have influenced migration flows over time. The movement of workers affects labor supply in both origin and destination countries and can alter patterns of production and consumption.

Migration can support economic integration by allowing labor to move to where it is most productive. It can also contribute to the transfer of skills and knowledge across countries. At the same time, migration can generate economic and social challenges, particularly when labor markets or public services face adjustment pressures.

International competitiveness

International competitiveness refers to the ability of a country’s firms to sell goods and services in global markets. It plays a central role in determining a country’s trade performance and its position in the balance of payments. Competitiveness depends on the prices at which goods and services can be sold, as well as on their quality, reliability, and suitability for consumer preferences.

Prices are influenced by several factors, including productivity, wages, input costs, and the exchange rate. If productivity grows faster than wages, unit labor costs fall, improving competitiveness. Similarly, a depreciation of the currency lowers the foreign currency price of exports, making them more attractive to overseas buyers.

Relative inflation rates also matter. If domestic prices rise more rapidly than prices in trading partner countries, competitiveness will tend to decline unless this is offset by exchange rate movements or productivity gains. Over time, sustained differences in inflation can have significant effects on trade performance.

Competitiveness is not solely about goods. Services play an increasingly important role in international trade. Countries that develop a comparative advantage in areas such as finance, technology, or professional services may perform strongly in global markets even if manufacturing plays a smaller role in their economies.

Absolute and comparative advantage

The pattern of international trade is closely linked to the concepts of absolute advantage and comparative advantage. Absolute advantage refers to a country’s ability to produce a good using fewer resources than another country. If one country can produce more of a good with the same amount of inputs, it has an absolute advantage in that good.

However, absolute advantage alone does not determine whether trade will be beneficial. What matters for specialization and trade is comparative advantage. Comparative advantage exists when a country can produce a good at a lower opportunity cost than another country. Opportunity cost measures what must be given up to produce one additional unit of a good in terms of other goods that could have been produced instead.

A country may have an absolute advantage in producing multiple goods, yet still benefit from trade by specializing in the good for which its opportunity cost is lowest. By specializing according to comparative advantage and trading with other countries, total global output can increase, allowing all trading partners to consume more than they could in the absence of trade.

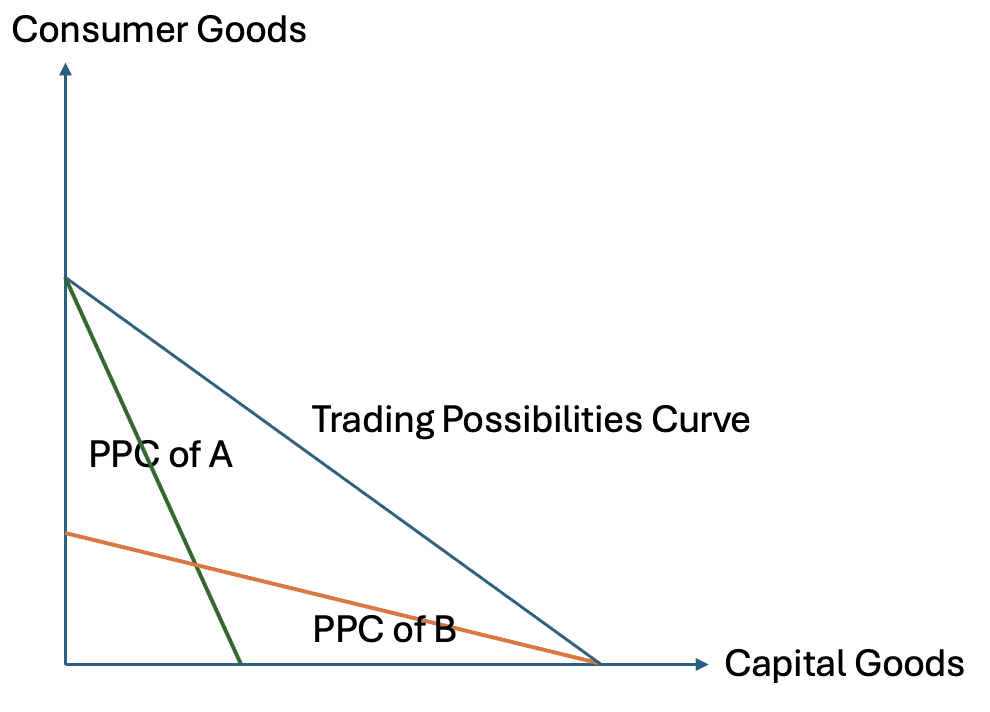

This logic can be illustrated using production possibility curves. Each country’s production possibility curve shows the combinations of goods that can be produced given current resources and technology. The slope of the curve reflects opportunity costs. Differences in these slopes indicate differences in comparative advantage. When countries specialize according to these differences and trade, their consumption possibilities expand beyond their individual production possibility curves.

The terms of trade

The gains from international trade depend not only on specialization but also on the terms at which trade takes place. The terms of trade are defined as the ratio of export prices to import prices. An improvement in the terms of trade means that export prices rise relative to import prices, allowing a country to obtain more imports for a given volume of exports. A deterioration means that export prices fall relative to import prices, requiring a larger volume of exports to purchase the same amount of imports.

Changes in the terms of trade are driven by movements in global prices and by changes in demand and supply conditions for exports and imports. They are calculated using price indices and do not directly account for changes in the volume of trade. As a result, a deterioration in the terms of trade does not necessarily imply that an economy is worse off if export volumes are increasing sufficiently.

The impact of changes in the terms of trade can vary across countries depending on the composition of their exports and imports. Countries that rely heavily on primary commodity exports may experience volatile terms of trade due to fluctuations in world commodity prices. This volatility can create uncertainty and affect income stability.

The J-curve effect and the Marshall Lerner condition

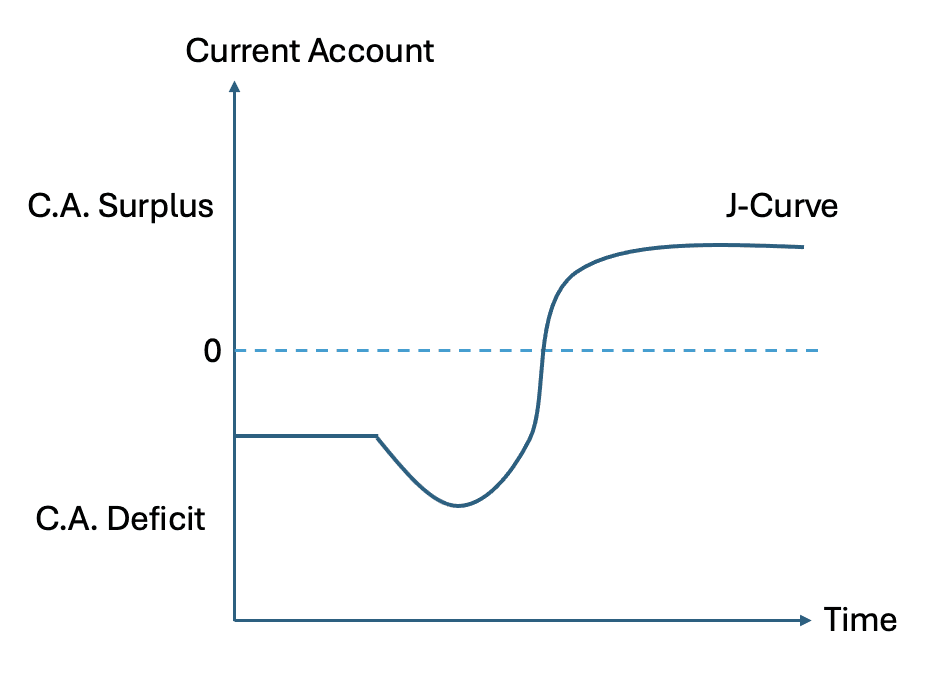

When a country seeks to improve its international competitiveness through a change in the exchange rate, it might be tempted to assume that a depreciation of the currency will automatically improve the current account. A lower value of the currency reduces the foreign currency price of exports and raises the domestic currency price of imports. In principle, this should increase the quantity demanded of exports and reduce the quantity demanded of imports, thereby improving the trade balance. However, this improvement does not necessarily occur immediately.

In the short run, the quantities of exports and imports often respond only weakly to changes in prices. Export contracts may already be in place, production capacity may be fixed, and consumers and firms may take time to adjust their purchasing behavior. As a result, following a depreciation, the value of imports measured in domestic currency may rise before quantities fall, while export revenues may not increase immediately. This can cause the current account position to worsen in the short run even though competitiveness has improved.

This time path of adjustment is known as the J curve effect. The current account initially moves further into deficit after a depreciation, before gradually improving as quantities respond to the new relative prices. Time is measured on the horizontal axis, and the current account balance on the vertical axis. The curve traces a path that resembles the letter J, first dipping downwards before rising above its initial level as the effects of increased export volumes and reduced import volumes take hold.

Whether a depreciation ultimately leads to an improvement in the current account depends on the responsiveness of export and import demand to price changes. This is captured by the Marshall Lerner condition. The Marshall Lerner condition states that a depreciation will improve the current account only if the sum of the price elasticities of demand for exports and imports is greater than one in absolute value. If demand is sufficiently elastic, the quantity effects of the price change will outweigh the adverse price effect on imports, leading to an improvement in export revenue relative to import expenditure.

If demand for exports is price inelastic, a fall in export prices will lead to only a small increase in export volumes, and export revenue may even fall. Similarly, if demand for imports is inelastic, higher import prices will not significantly reduce import volumes, and import expenditure may rise. In this case, a depreciation may fail to improve the current account even in the long run. The Marshall Lerner condition therefore provides a key theoretical framework for evaluating the effectiveness of exchange rate changes as a tool for improving trade performance.

Comparative advantage and the pattern of international trade

Comparative advantage provides a powerful explanation for the observed pattern of international trade. Countries tend to specialize in producing goods and services for which they have a lower opportunity cost relative to other countries. Globalisation can be understood as a process that allows countries to exploit their comparative advantage more fully by expanding access to international markets.

As countries specialize, the structure of their economies changes. Resources are reallocated toward industries in which comparative advantage is strongest, while less competitive industries may contract. This process can increase overall productivity and raise global output, but it also requires adjustment. Workers may need to move between sectors, acquire new skills, or adapt to changes in employment opportunities.

The pattern of comparative advantage is not fixed. It can evolve over time as countries invest in education, infrastructure, and technology. Policies that support skill development and capital accumulation can shift comparative advantage toward higher value added activities. Globalisation can therefore both reflect existing comparative advantage and contribute to its transformation.

Some countries, particularly developing economies, may find themselves specializing in primary goods or low value added activities. While this specialization may reflect comparative advantage, it can also limit opportunities for income growth if demand for these products is volatile or grows slowly. Diversifying into manufacturing or services may be desirable, but achieving this transition can be difficult and may require supportive policies and investment.

Consequences of globalisation

Globalisation has wide ranging consequences for economies, governments, firms, workers, and consumers. These consequences are not uniform and differ across countries and groups within countries. At the center of the process is increased interdependence, which amplifies both opportunities and risks.

Standards of living

By enabling greater specialization and trade, globalisation has supported economic growth in many countries. Higher productivity and access to larger markets have contributed to rising standards of living, particularly in economies that have successfully integrated into global trade networks. Consumers benefit from a wider range of goods and services, often at lower prices, increasing real incomes and choice.

In developed economies, consumers have gained access to a broader array of imported products, while firms have benefited from cheaper intermediate inputs. In emerging economies, export led growth has supported rapid increases in income and employment in certain sectors. However, the benefits have not always been evenly distributed, and some groups have experienced limited gains or even losses.

Structural change

Globalisation accelerates structural change by altering the relative competitiveness of different sectors. Industries that face increased competition from lower cost producers may shrink, while others expand. This process can involve significant transitional costs. Workers displaced from declining industries may struggle to find employment in expanding sectors, particularly if their skills are not easily transferable.

Over time, economies may benefit from this reallocation as resources move toward more productive uses. However, the short run costs can be substantial, and adjustment may be slow. The distributional consequences of structural change are therefore an important concern in evaluating globalisation.

Foreign direct investment and multinational corporations

A central feature of globalisation has been the growth of foreign direct investment undertaken by multinational corporations. Foreign direct investment involves establishing or expanding productive capacity in another country, rather than simply trading goods or services. Multinational corporations operate across multiple countries and play a major role in organizing global production.

There are several motives for foreign direct investment. Firms may seek access to new markets by producing within them rather than exporting. They may seek access to natural resources or specific inputs. They may also seek efficiency gains by locating different stages of production in countries where costs are lowest.

Foreign direct investment can bring benefits to host countries, including employment, tax revenue, capital, and technology transfer. It can support economic growth and integration into global markets. However, there are also potential downsides. Profits may be repatriated rather than reinvested locally, and the benefits may be unevenly distributed. In some cases, host countries may offer tax concessions that reduce the net fiscal gain.

Interdependence and vulnerability

As economies become more closely integrated, they become more exposed to shocks originating elsewhere. A downturn in one major economy can reduce demand for exports in others. Financial integration can transmit crises rapidly across borders. While interdependence allows countries to share in periods of global growth, it also increases the risk that problems will spread during downturns.

Globalisation therefore raises questions about resilience and stability. The ability of economies to cope with shocks depends on their flexibility, policy frameworks, and institutional strength. Coordination between countries may be required to manage global challenges effectively.

The environment

Increased economic activity associated with globalisation has implications for the environment. Higher levels of production and trade can increase resource use and emissions, contributing to environmental degradation and climate change. The environmental impact of globalisation depends on production methods, energy use, and regulatory frameworks.

Economic growth can provide resources for environmental protection and technological innovation. However, without appropriate policies, increased trade and production may exacerbate environmental problems. Balancing economic integration with environmental sustainability is therefore a key challenge.

The impact of emerging economies

The rise of emerging economies has been one of the most significant developments associated with globalisation. Rapid economic growth in countries such as China has reshaped global trade patterns, production structures, and economic power. These economies have become major exporters and importers, influencing prices, supply chains, and investment flows.

The growth of emerging economies has created opportunities for developed economies through access to new markets and lower cost goods. At the same time, it has increased competition for domestic producers in developed economies. The shift in global economic weight has also raised geopolitical and policy challenges.

Emerging economies have benefited from integrating into global markets, but their experiences have varied. Some have achieved sustained growth and rising living standards, while others have struggled to translate integration into broad based development. The outcomes depend on domestic policies, institutions, and the ability to adapt to global economic conditions.