Macroeconomics Chapter 17: Trade Policies

This chapter explores the concepts of trade policies, their benefits and problems, as well as trade agreements.

Introduction to trade policy in a globalized economy

International trade expanded rapidly in the decades following the Second World War, driven by deliberate efforts to reduce barriers between national economies and to promote closer economic integration. Trade agreements, customs unions, and broader forms of cooperation lowered tariffs and other restrictions, encouraging countries to specialize according to comparative advantage and to participate in global supply chains. This process increased interdependence between economies and contributed to rising global output and living standards.

At the same time, international trade has never been universally accepted without resistance. Governments have often been reluctant to allow completely free trade, particularly when domestic industries face competition from abroad or when economic downturns increase political pressure to protect jobs and incomes. In more recent years, this tension has become more visible, with a renewed emphasis on national trade policy, including the use of tariffs and other restrictive measures. Trade policy therefore sits at the intersection of economic theory, political decision making, and international negotiation.

Trade policies refer to the measures governments use to influence the volume, composition, and direction of international trade. These policies may be designed to restrict trade, encourage trade, or shape the terms on which trade takes place. Understanding trade policy requires an examination of both protectionism and free trade, as well as the institutional frameworks through which countries negotiate and coordinate their policies.

Protectionism

Protectionism refers to measures taken by a government to restrict international trade in order to protect domestic producers from foreign competition. These measures can take a variety of forms, but they all have the effect of reducing imports, raising the domestic price of foreign goods, or limiting access to the domestic market.

The motivation for protectionism often arises from concerns about domestic industries, employment, or strategic interests. When foreign producers are able to supply goods at lower prices, domestic firms may lose market share, leading to job losses and declining output in affected sectors. Governments may respond by intervening in trade to shield these industries from competition.

However, protectionism must be understood in the context of comparative advantage. Even though trade allows consumers to benefit from lower prices and greater choice, and allows resources to be allocated more efficiently across the economy, the gains from trade are not always evenly distributed. Some groups benefit, while others lose. Protectionist policies are often justified politically as a way to support those who are adversely affected by trade.

Tariffs

One of the most common instruments of protectionism is the tariff. A tariff is a tax imposed on imported goods. By raising the price of imported products, a tariff makes domestically produced substitutes relatively more attractive to consumers.

To understand the effects of a tariff, consider a market in which a good can be imported at the world price. At this price, domestic demand exceeds domestic supply, and the difference is met by imports. The world price is assumed to be given, reflecting conditions in global markets that the importing country cannot influence.

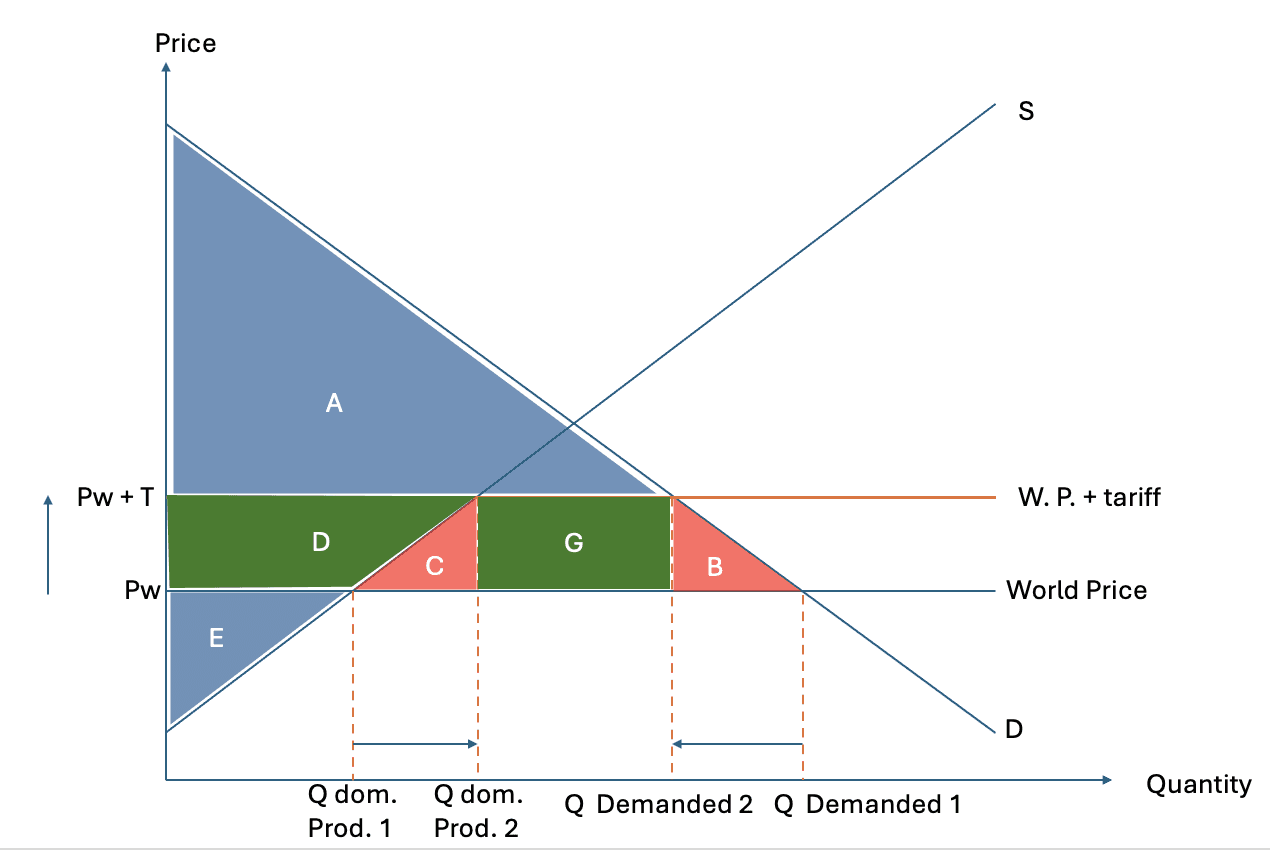

The diagram shows how a tariff redistributes and reduces welfare. Area D is the gain in producer surplus from the higher price, while area G is tariff revenue received by the government. Areas B and C represent deadweight welfare losses, with B showing the reduction in consumption and C showing inefficient expansion of higher-cost domestic production. Area A shows the new consumer surplus from the price increase, while area E shows the original producer surplus at the world price before the tariff. Overall, the loss to consumers exceeds the gains to producers and government, so total welfare falls.

On the diagram, price is measured on the vertical axis and quantity on the horizontal axis. The domestic demand curve slopes downward, reflecting the inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded. The domestic supply curve slopes upward, showing that higher prices encourage greater domestic production. The world supply curve is drawn as a horizontal line at the world price, indicating that the good can be supplied in unlimited quantities at that price.

In the absence of a tariff, consumers pay the world price, domestic producers supply a portion of total demand, and imports fill the gap between domestic demand and domestic supply. Consumer surplus is large because consumers benefit from the low world price. Producer surplus is smaller, reflecting the relatively low price received by domestic firms.

When a tariff is imposed, the domestic price rises by the amount of the tariff. This higher price reduces quantity demanded and increases quantity supplied by domestic producers. As a result, imports fall. The tariff therefore achieves two immediate objectives. It reduces reliance on imports and encourages domestic production.

The welfare effects of the tariff are more complex. Consumers are worse off because they pay a higher price and consume less of the good. Consumer surplus falls. Domestic producers benefit from the higher price and increased output, leading to an increase in producer surplus. The government also gains revenue from the tariff, equal to the tariff per unit multiplied by the quantity of imports that remain after the tariff is imposed.

However, there is also a loss to society as a whole. Part of the loss in consumer surplus is transferred to producers and the government, but some of it is lost entirely. This deadweight loss arises because the tariff causes resources to be allocated inefficiently. Domestic producers expand output even though they are less efficient than foreign producers, and consumers are discouraged from purchasing goods that they value more than the world price but less than the tariff inclusive price.

Overall, the tariff makes society worse off, even though certain groups gain. The existence of these concentrated gains and diffuse losses helps explain why tariffs persist despite their negative impact on overall welfare.

Quotas and non tariff barriers

An alternative to tariffs is the use of quotas. A quota is a quantitative restriction on the amount of a good that can be imported. Rather than raising the price through a tax, a quota limits supply directly.

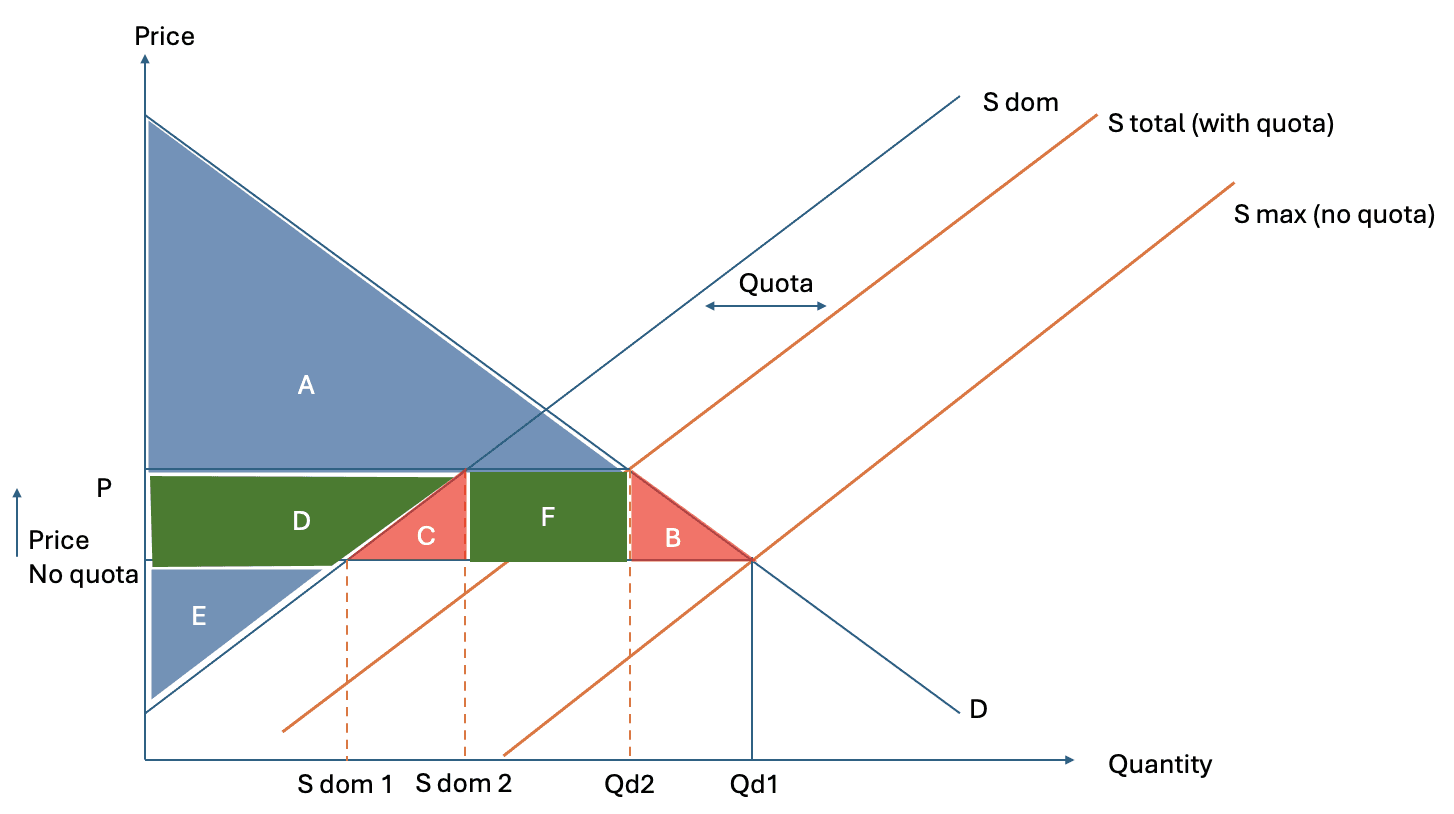

The diagram shows the welfare effects of an import quota. Area D is the gain in producer surplus as domestic firms receive a higher price and expand output. Area F represents quota rents, which arise from the restricted supply of imports and accrue to whoever holds the import licenses. Areas B and C are deadweight welfare losses, with B showing the consumption loss from higher prices and C showing inefficient expansion of domestic production. Area A shows the loss of consumer surplus due to the price increase, while area E shows producer surplus at the free trade price. Overall, total welfare falls because the losses to consumers exceed the gains to producers and quota holders.

The diagram used to analyze a quota is similar to that for a tariff. At the world price, domestic demand exceeds domestic supply, and imports fill the gap. When a quota is imposed, total supply becomes the sum of domestic supply and the fixed quantity of imports allowed under the quota. This creates a vertical or kinked supply curve at the quota limit.

The restriction on imports raises the domestic price, reducing quantity demanded and increasing domestic production. As with a tariff, consumers lose and domestic producers gain. The key difference lies in who receives the revenue created by the higher price. With a tariff, the government collects revenue. With a quota, the additional revenue takes the form of quota rents, which may accrue to foreign exporters or to domestic firms granted import licenses.

The welfare effects of a quota are therefore similar to those of a tariff, but potentially worse, since the government does not necessarily receive revenue. In addition, quotas can be less transparent and more prone to political manipulation, as decisions about who receives import licenses can be influenced by lobbying and favoritism.

Beyond tariffs and quotas, governments may use non tariff barriers to restrict trade. These include regulations, standards, and administrative procedures that make it more difficult or costly for foreign goods to enter the domestic market. Examples include product safety standards, labeling requirements, and customs procedures. While such measures may be justified on health, safety, or environmental grounds, they can also be used deliberately to protect domestic producers.

Advantages and disadvantages of protectionism

The debate over protectionism centers on whether its potential benefits outweigh its costs. Supporters of protectionism argue that it can protect domestic employment, support strategic industries, and allow time for industries to adjust to international competition. Critics emphasize the loss of consumer welfare, the inefficiency created by distorted prices, and the risk of retaliation by trading partners.

One common argument in favor of protectionism is the protection of infant industries. An infant industry is a new or emerging industry that may initially be unable to compete with established foreign producers but could become competitive over time. Temporary protection may allow the industry to grow, achieve economies of scale, and develop the skills and technology needed to compete internationally.

Another argument relates to declining industries. Protection may be used to slow the decline of industries facing long term structural change, reducing the social costs associated with unemployment and regional decline. However, this argument often blurs into a broader debate about whether resources should be allowed to move freely to more productive uses.

Against these arguments, critics point out that protection can become permanent, even when the original justification no longer applies. Firms protected from competition may have little incentive to improve efficiency or innovate. Over time, this can lead to higher costs, lower productivity, and reduced international competitiveness.

Protectionism also risks retaliation. When one country imposes trade barriers, others may respond in kind. This can reduce global trade, lower economic growth, and leave all countries worse off. The potential for such outcomes has been a major motivation behind efforts to create international rules and institutions to govern trade.

The impact of protectionism

Protectionist policies have wide ranging effects on different groups within an economy. Although these effects depend on the specific measure used, such as a tariff or a quota, the general consequences can be analyzed by examining how protection alters prices, quantities, and incentives in domestic markets. The most common form of protectionist policy is the tariff, and it provides a clear framework for understanding these impacts.

Consumers

Consumers are generally made worse off by protectionist measures. When a tariff or quota raises the domestic price of a good, consumers must pay more for each unit they purchase. As prices rise, quantity demanded falls, meaning that consumers either reduce consumption or substitute toward other goods that may be less preferred. This reduction in consumption represents a loss of consumer surplus.

Consumer surplus measures the difference between what consumers are willing to pay for a good and what they actually pay. Before protection is introduced, the low world price allows consumers to enjoy a large surplus. After the tariff is imposed and the price rises, this surplus is reduced. Part of the loss is a transfer to producers and, in the case of a tariff, to the government. However, part of the loss represents a deadweight welfare loss, reflecting consumption that no longer takes place even though consumers value the good more than its world cost of production.

The effect on consumers is particularly significant for goods that make up a large share of household spending. When protection is applied to essential goods or inputs into other products, the higher prices can reduce real incomes and living standards across the economy.

Producers

Domestic producers benefit directly from protectionist measures. Higher prices allow firms to increase output and sell at a price above the world level. As a result, producer surplus rises. This increase in surplus reflects both higher prices on existing output and additional output produced at the higher price.

However, the gain to producers does not necessarily imply an improvement in productive efficiency. Protection allows firms that are less efficient than foreign competitors to survive and expand. In the absence of competition, these firms may have weaker incentives to innovate, reduce costs, or improve quality. Over time, this can lead to X inefficiency, where firms operate above their minimum average cost.

In the long run, protection may delay structural change. Resources remain tied up in industries where the country does not have a comparative advantage, rather than moving toward sectors with higher productivity and growth potential. As a result, the initial gains to producers may come at the expense of long term economic performance.

Governments

Governments may gain revenue from protectionist measures, particularly in the case of tariffs. Tariff revenue is equal to the tariff per unit multiplied by the quantity of imports that remain after the tariff is imposed. This revenue can be used to fund public spending or reduce other forms of taxation.

For some countries, especially those with limited administrative capacity to collect income or consumption taxes, tariffs may represent an important source of government revenue. However, as tariffs restrict imports, the tax base may shrink over time, limiting the revenue raised.

In the case of quotas, governments do not necessarily receive revenue. The higher price created by the quota generates quota rents, which may accrue to foreign exporters or to domestic firms granted import licenses. From the government’s perspective, this makes quotas a less efficient instrument than tariffs.

Governments also face broader economic and political consequences. Protectionist measures can provoke retaliation from trading partners, leading to reduced exports and higher prices for imported inputs. This can undermine domestic industries that rely on global supply chains and reduce overall economic welfare.

Living standards

From the perspective of society as a whole, protectionism reduces living standards. The higher prices paid by consumers, combined with the inefficient allocation of resources, generate a deadweight loss to the economy. This loss represents output that could have been produced and consumed but is not, due to distorted incentives.

Living standards are determined by the economy’s ability to produce goods and services efficiently and to allocate them according to preferences. By encouraging production in sectors where the country is relatively inefficient, protectionism lowers overall productivity and reduces the range of goods available to consumers.

Although protection may support employment in specific industries, this benefit must be weighed against the higher costs faced by consumers and firms in other sectors. In many cases, the net effect is a reduction in real income and economic welfare.

Equality

Protectionist policies also have distributional effects. By raising prices, they tend to transfer income from consumers to producers. Since consumers include virtually all households, while producers are concentrated in specific industries, protection may increase inequality.

Lower income households are often disproportionately affected by higher prices, particularly when protection applies to basic goods. At the same time, the benefits accrue to a relatively small group of firms and workers in protected industries. As a result, protectionism can worsen income distribution even if it is justified politically as a way to protect jobs.

Free trade

Free trade refers to the absence of government imposed restrictions on international trade. Under free trade, goods and services move across borders without tariffs, quotas, or non tariff barriers. The case for free trade is rooted in the theory of comparative advantage, which shows that countries can gain from specializing in the production of goods for which they have a lower opportunity cost and trading with others.

Under free trade, consumers benefit from lower prices, greater choice, and higher quality goods. Producers gain access to larger markets, allowing them to exploit economies of scale and specialize more fully. Resources are allocated toward their most productive uses, raising overall efficiency and output.

Despite these benefits, free trade remains controversial. The gains from trade are unevenly distributed, and adjustment costs can be significant. Workers and firms in industries that face increased competition may suffer losses, even as the economy as a whole gains. These adjustment costs are a central reason why governments intervene in trade.

Economic integration

Economic integration refers to agreements between countries to reduce or eliminate barriers to trade and to coordinate economic policies. Integration can take several forms, each representing a deeper level of cooperation between member countries.

A free trade area involves the removal of tariffs and quotas on trade between member countries, while each country retains its own trade policy toward non members. This arrangement encourages trade within the area but can create incentives for trade to be diverted through the member with the lowest external tariffs.

A customs union goes further by establishing a common external tariff against non members. This eliminates the problem of trade deflection but requires greater coordination between member countries. Customs unions are designed to promote trade between members while simplifying trade policy.

A common market extends integration by allowing the free movement of factors of production, including labor and capital, between member countries. This requires harmonization of regulations and policies to ensure fair competition and efficient allocation of resources.

An economic and monetary union represents the deepest form of integration. Member countries adopt a common currency or permanently fix exchange rates and coordinate monetary policy. This arrangement eliminates exchange rate uncertainty but requires a high degree of policy coordination and economic convergence.

Trade creation and trade diversion

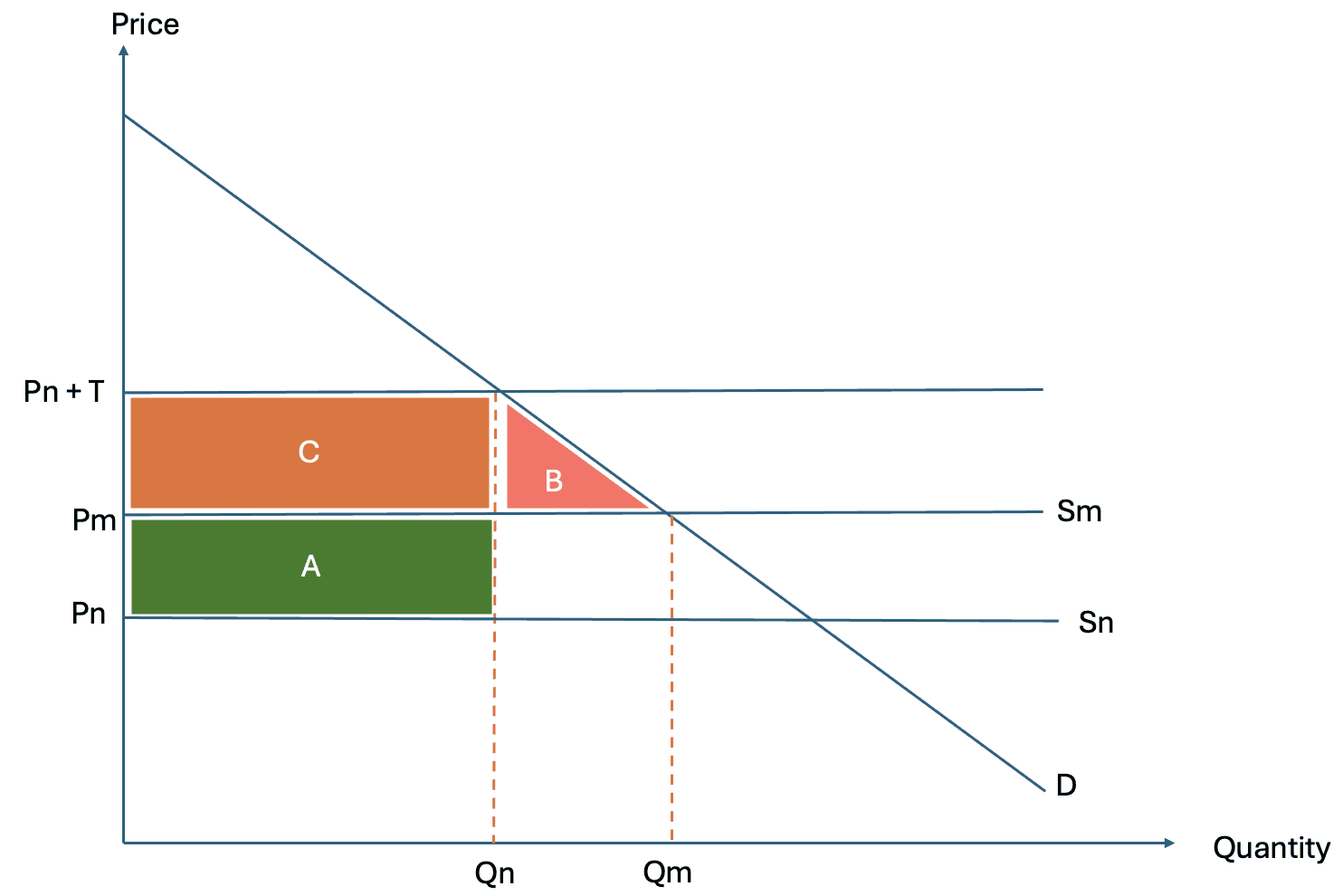

Economic integration can lead to trade creation and trade diversion. Trade creation occurs when high cost domestic production is replaced by lower cost imports from a partner country. This represents a gain in efficiency and welfare, as resources are reallocated toward more productive uses.

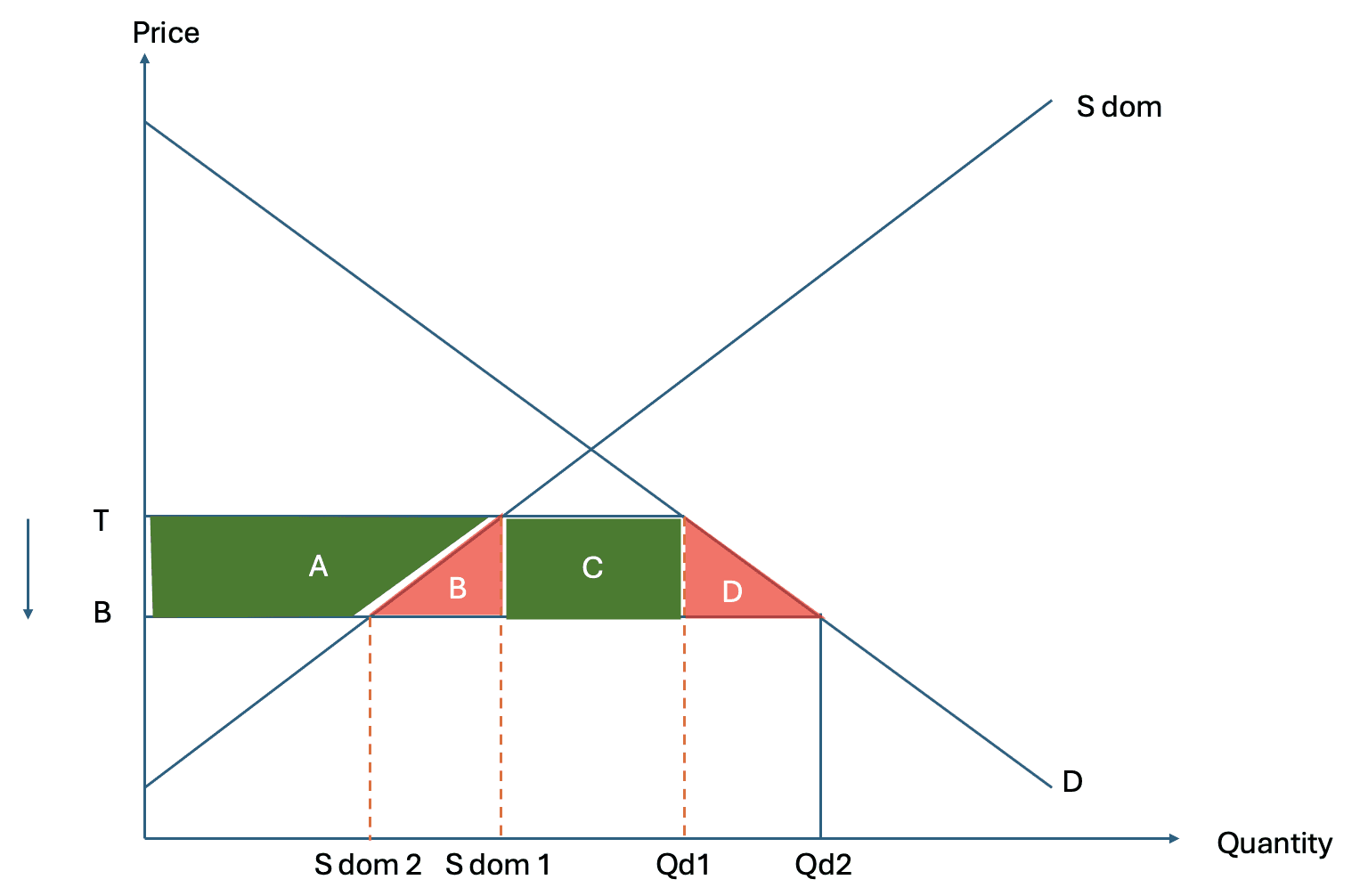

The diagram shows trade creation following entry into a trading bloc. Area A represents the gain in consumer surplus from the fall in price, while area C represents the gain from replacing higher-cost domestic production with lower-cost imports from a partner country. Areas B and D represent redistribution and adjustment effects as domestic production contracts and consumption expands. Overall, trade creation increases total welfare because production shifts toward more efficient producers within the trading bloc.

Trade diversion occurs when imports from a low cost non member country are replaced by higher cost imports from a member country, due to the common external tariff. In this case, trade patterns change, but overall efficiency may fall.

The diagram shows trade diversion following entry into a trading bloc. Area A represents the loss of tariff revenue previously collected on imports from the most efficient external producer. Area C shows the transfer of surplus to higher-cost partner country producers, while area B represents a deadweight welfare loss from switching away from the lowest-cost source of supply. Overall, trade diversion may reduce total welfare because imports are redirected from a more efficient external producer to a less efficient partner within the bloc.

The net effect of economic integration depends on the balance between trade creation and trade diversion. If trade creation dominates, integration raises welfare. If trade diversion dominates, integration may reduce welfare, even though trade within the bloc increases.

Evaluation of trade policies and negotiations

Trade policies reflect a balance between economic efficiency and political considerations. While free trade maximizes overall welfare, protectionist measures are often adopted to address distributional concerns, strategic interests, or adjustment costs. International trade negotiations aim to reduce barriers while providing mechanisms to manage these concerns.

The role of international institutions is to facilitate cooperation, reduce the risk of retaliation, and promote predictable trading rules. By establishing common frameworks and dispute resolution mechanisms, these institutions help countries capture the gains from trade while limiting the costs of conflict.

Trade negotiations and the role of international institutions

As countries pursue their own trade policies, conflicts of interest inevitably arise. While each country may benefit individually from protecting its domestic industries, widespread protectionism reduces global trade and leaves all countries worse off. This creates a collective action problem, in which cooperation is required to secure mutually beneficial outcomes. International trade negotiations and institutions have developed in response to this problem.

Trade negotiations aim to reduce barriers to trade through reciprocal agreements. By committing simultaneously to lower tariffs and other restrictions, countries can increase trade while limiting the political costs associated with unilateral liberalization. Negotiations also help establish common rules, increasing predictability and reducing uncertainty for firms engaged in international trade.

Following the Second World War, efforts to liberalize trade were coordinated through a series of multilateral agreements. These agreements sought to reduce tariffs gradually, address non tariff barriers, and create a stable framework for international trade relations. Over time, this process led to the creation of a permanent institution to oversee trade rules and negotiations.

The World Trade Organization

The World Trade Organization is the central institution governing international trade relations. Its primary role is to promote free trade by providing a framework for negotiating trade agreements, monitoring national trade policies, and resolving disputes between member countries.

One of the key functions of the organization is to oversee rounds of trade negotiations aimed at reducing tariffs and other barriers. These negotiations are based on the principle of reciprocity, meaning that countries agree to open their markets in exchange for similar concessions from others. This approach helps ensure that the benefits of liberalization are shared and that no single country bears the full adjustment cost alone.

Another important principle underpinning the system is non discrimination. Under this principle, countries are expected to treat all trading partners equally, applying the same tariffs and trade rules unless a formal trade agreement exists. This reduces the scope for arbitrary discrimination and helps create a level playing field for international trade.

The organization also plays a crucial role in dispute settlement. When countries believe that others have violated trade rules, they can bring a case through the dispute resolution process. This provides a structured mechanism for resolving conflicts without resorting to unilateral retaliation. Although enforcement ultimately depends on the willingness of member countries to comply, the existence of a formal process increases transparency and accountability.

Despite its importance, the organization faces significant challenges. Negotiations have become increasingly complex as the number of member countries has grown and as trade barriers have shifted away from tariffs toward regulations and standards. Disagreements between advanced and developing economies over priorities and responsibilities have made progress difficult. As a result, regional and bilateral trade agreements have become more prominent alongside multilateral negotiations.

Regional trade agreements

In addition to global negotiations, countries often pursue regional trade agreements. These agreements involve a smaller group of countries and may allow for deeper integration than is possible at the global level. By focusing on regional partners, countries may find it easier to reach agreement on common rules and standards.

However, regional agreements can create tensions with the multilateral trading system. While they promote free trade within the group, they may also divert trade away from more efficient producers outside the agreement. The overall welfare impact depends on whether trade creation exceeds trade diversion.

Regional agreements also raise questions about consistency with global trade rules. While they are permitted under certain conditions, there is a risk that overlapping agreements create a complex and fragmented trading system. This can increase administrative costs and complicate trade relationships.

Evaluation of trade policies

The evaluation of trade policies requires balancing economic efficiency against social, political, and strategic considerations. From a purely economic perspective, free trade maximizes overall welfare by allowing countries to specialize according to comparative advantage and by promoting efficient allocation of resources. Protectionist measures reduce welfare by raising prices, distorting incentives, and generating deadweight losses.

However, economic outcomes do not occur in a vacuum. Adjustment costs, distributional effects, and concerns about national resilience influence policy choices. While protectionism can provide temporary relief to specific industries or regions, it often does so at a high cost to consumers and the broader economy.

Trade negotiations and international institutions attempt to reconcile these competing objectives. By coordinating liberalization and establishing common rules, they seek to capture the gains from trade while managing its consequences. The effectiveness of these arrangements depends on trust, compliance, and the willingness of countries to prioritize long term collective benefits over short term national interests.