Macroeconomics Chapter 18: Money and Interest Rate

This chapter explores the concepts of types of money in the economy and interest rate.

Introduction to money and its role in the economy

Money plays a central role in the functioning of a modern economy because it facilitates exchange, allows economic value to be measured, and enables transactions to take place over time. Without money, exchange would rely on barter, which requires a double coincidence of wants. This means that each party to a transaction must want exactly what the other is offering at the same time. In a complex economy with millions of goods, services, and participants, such a system would severely limit trade and specialization. Money overcomes this problem by acting as a commonly accepted medium that can be exchanged for goods and services.

Beyond facilitating exchange, money influences the overall performance of the economy through its relationship with inflation, output, and interest rates. Changes in the quantity of money and in the way money circulates through the economy affect aggregate demand, price levels, and financial conditions. As a result, understanding money is essential for understanding macroeconomic outcomes.

Despite its importance, money is not easy to define or measure precisely. In modern economies, money exists in many forms, ranging from cash to bank deposits and other highly liquid financial assets. Some of these forms are directly controlled by the central bank, while others are created through the activities of commercial banks. This makes the analysis of money supply and its effects more complex than simply counting banknotes and coins.

The functions of money

Money performs four key functions that allow it to support economic activity effectively. The first function is that money acts as a medium of exchange. This means that money is used to buy and sell goods and services and is accepted by both buyers and sellers in transactions. For money to perform this function, it must be widely accepted and trusted as a means of payment. If sellers believed that money could not be used in future transactions, they would refuse to accept it.

The second function of money is that it acts as a store of value. Money allows individuals and firms to transfer purchasing power from the present into the future. Income does not need to be spent immediately, and money can be held to make purchases at a later date. This function requires that money retains its value reasonably well over time. If money rapidly loses value due to high inflation, its usefulness as a store of value is reduced.

The third function of money is that it acts as a unit of account. Money provides a common measure by which the value of goods, services, and assets can be compared. Prices expressed in monetary terms allow consumers and firms to assess relative values and make informed decisions. Without a unit of account, economic calculation would be extremely difficult, as each good would need to be compared directly with every other good.

The fourth function of money is that it acts as a standard of deferred payment. Many economic transactions involve payments that are agreed upon now but made in the future. Examples include wages, rent, loans, and contracts for future delivery. Money provides a standard unit in which these future obligations can be specified. For this function to operate effectively, money must retain a predictable value over time.

The characteristics of money

To perform these functions effectively, money must possess certain characteristics. Money must be portable so that it can be easily carried and transferred. It must be divisible so that it can be broken into smaller units to facilitate transactions of different sizes. Money must be acceptable, meaning that it is widely recognized and trusted as a means of exchange.

Money must also be scarce, in the sense that it cannot be freely available in unlimited quantities, otherwise it would lose value. At the same time, it must be difficult to counterfeit so that confidence in its value is maintained. Durability is another important characteristic, as money needs to withstand repeated use without deteriorating. Finally, money must have stability in value so that it can function effectively as both a store of value and a standard of deferred payment.

While many commodities have served as money at various points in history, not all of them meet these characteristics equally well. Modern economies rely primarily on fiat money, whose value is based on trust and legal acceptance rather than intrinsic worth.

Money in the modern economy

In a modern economy, money consists of more than just notes and coins. While cash issued by the central bank is an important component, a large proportion of money exists in the form of bank deposits. These deposits can be used to make payments through checks, debit cards, and electronic transfers, and therefore function in the same way as cash for most transactions.

The central bank can measure and monitor the quantity of physical money relatively easily. However, measuring broader forms of money is more complex because it involves assets that vary in liquidity. Liquidity refers to how easily an asset can be converted into a means of payment without loss of value. Cash is perfectly liquid, while other financial assets, such as savings accounts or bonds, are less liquid because converting them into cash may take time or involve costs.

Because many assets closely resemble money in their function, it is difficult to draw a clear boundary between what counts as money and what does not. This complicates attempts by the central bank to control the money supply and assess its impact on the economy.

Narrow money and broad money

One way of addressing this issue is to define different measures of the money supply based on liquidity. Narrow money refers to the most liquid forms of money that are used primarily for transactions. This includes notes and coins in circulation and certain types of bank deposits that can be accessed immediately.

Broad money includes narrow money plus less liquid forms of money, such as savings deposits and other bank deposits that may not be used directly for transactions but can still be converted into spending power relatively easily. Broad money therefore captures the wider pool of financial resources that can influence spending and inflation.

Although narrow money is closely linked to transactions, broad money may be more relevant for understanding wealth, credit conditions, and longer-term economic trends. However, broader measures of money are also more difficult to control, as they depend heavily on the behavior of commercial banks and the preferences of households and firms.

Credit creation by commercial banks

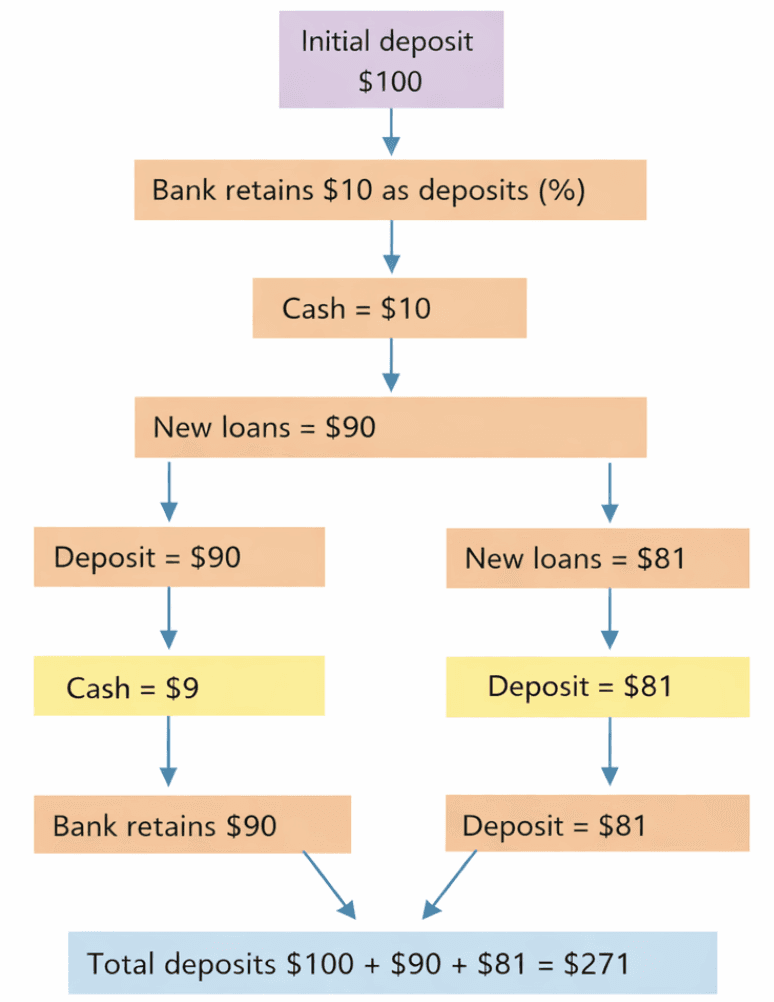

A key reason why the money supply is difficult to control is that commercial banks play an active role in creating money through their lending activities. Banks accept deposits from customers and provide loans to borrowers. When a bank makes a loan, it does not usually lend out existing cash. Instead, it creates a new deposit in the borrower’s account. This deposit can then be spent, adding to the money supply.

Banks do not lend out all the deposits they receive. They hold a proportion of their assets in liquid form to meet withdrawals and payments. The rest can be lent out. When loan recipients spend their funds, the money often ends up deposited in another bank, which can then lend out a portion of that deposit again. This process continues through the banking system, leading to a multiplied increase in bank deposits and loans.

This process is known as the credit creation multiplier. The size of the multiplier depends on the proportion of deposits that banks choose to hold as liquid reserves. The lower this proportion, the larger the potential expansion of credit. Conversely, if banks become more cautious and hold higher reserves, the expansion of credit will be smaller.

The credit creation process means that changes in bank behavior can have a significant impact on the money supply. It also means that the central bank cannot directly control the total quantity of money in the economy, even if it controls the supply of base money.

Money and inflation

The quantity of money and credit in circulation plays a crucial role in determining the overall price level in the economy. Classical economists argued that there is a close and predictable relationship between money supply and inflation. According to this view, persistent inflation cannot occur unless the quantity of money in the economy grows persistently faster than real output. Temporary price increases may arise from other factors, but sustained inflation requires continued monetary expansion.

The reasoning behind this view begins with the idea that money is used to facilitate transactions. If the supply of money increases while the volume of goods and services available for purchase remains unchanged, then more money is chasing the same quantity of output. Firms respond to higher demand by raising prices, and the overall price level increases. If money supply growth continues, inflation becomes persistent rather than temporary.

This approach does not deny that changes in demand or supply conditions can affect prices in the short run. Instead, it argues that without continued growth in money supply, these price changes cannot be sustained. Over time, inflation reflects monetary conditions rather than real economic activity.

The Fisher equation of exchange

The relationship between money and inflation is summarized by the Fisher equation of exchange.

This equation states that the money supply multiplied by the velocity of circulation equals the price level multiplied by real output. Velocity of circulation refers to the speed at which money changes hands in the economy. It measures how frequently a unit of money is used to purchase goods and services over a given period.

If velocity is stable, changes in the money supply translate directly into changes in nominal spending. If real output grows at a steady rate, then increases in nominal spending must show up as increases in the price level. Under these assumptions, inflation is driven by growth in the money supply in excess of real output growth.

The equation itself is an identity, meaning it is always true by definition. It only becomes a theory when assumptions are made about the behavior of velocity and output. Classical economists assumed that velocity was constant and that output tended to return quickly to its full employment level. Under these conditions, changes in money supply determine changes in the price level.

Limitations of the quantity theory

In practice, the assumptions underlying the quantity theory may not hold. Velocity of circulation can change over time due to developments in financial markets, payment technologies, and preferences for holding money. During periods of uncertainty, households and firms may hold onto money rather than spending it, causing velocity to fall.

Real output may also deviate from its full employment level for extended periods. If there is spare capacity in the economy, increases in money supply may lead to higher output rather than higher prices, at least in the short run. This weakens the direct link between money growth and inflation.

As a result, the relationship between money supply and inflation is less predictable in the short run. However, many economists continue to argue that over long periods, sustained inflation remains closely linked to sustained monetary expansion.

Real and nominal interest rates

When inflation is present, it is important to distinguish between nominal and real interest rates. The nominal interest rate is the rate quoted on financial assets and loans. It represents the percentage increase in money received by a lender over a given period. However, this does not account for changes in purchasing power due to inflation.

The real interest rate adjusts the nominal interest rate for inflation. It measures the increase in purchasing power received by the lender. A simple approximation for the real interest rate is the nominal interest rate minus the rate of inflation. If the nominal interest rate is lower than inflation, the real interest rate is negative, meaning that lenders lose purchasing power over time.

This distinction matters for saving and investment decisions. Firms base investment decisions on the real cost of borrowing, not the nominal rate. Similarly, households consider the real return on savings when deciding how much to save.

The determination of interest rates

Interest rates play a central role in linking money markets to the wider economy. One way of understanding interest rate determination is through the demand for and supply of money. The interest rate can be interpreted as the opportunity cost of holding money rather than interest bearing assets.

The demand for money arises because households and firms need money for transactions, precautionary purposes, and speculative reasons. Transaction demand depends largely on income, as higher income leads to a greater volume of transactions. Precautionary demand reflects the desire to hold money to meet unexpected expenses. Speculative demand reflects expectations about future interest rates and asset prices.

The supply of money is determined by the monetary authorities, but the broader money supply also depends on the behavior of commercial banks and borrowers. Given a fixed money supply, the interest rate adjusts to ensure that money demand equals money supply.

Liquidity preference

The theory of liquidity preference explains how interest rates are determined through the interaction of money supply and money demand. According to this theory, the demand for money is inversely related to the interest rate. When interest rates are high, the opportunity cost of holding money is high, so people prefer to hold interest bearing assets. When interest rates are low, holding money becomes more attractive.

For a given money supply, changes in money demand lead to changes in the interest rate. An increase in money supply, with money demand unchanged, leads to excess supply of money and puts downward pressure on the interest rate. Conversely, an increase in money demand raises the interest rate if the money supply is fixed.

This framework highlights a key constraint on monetary policy. The central bank cannot independently fix both the money supply and the interest rate. Choosing one requires allowing the other to adjust.

The market for loanable funds

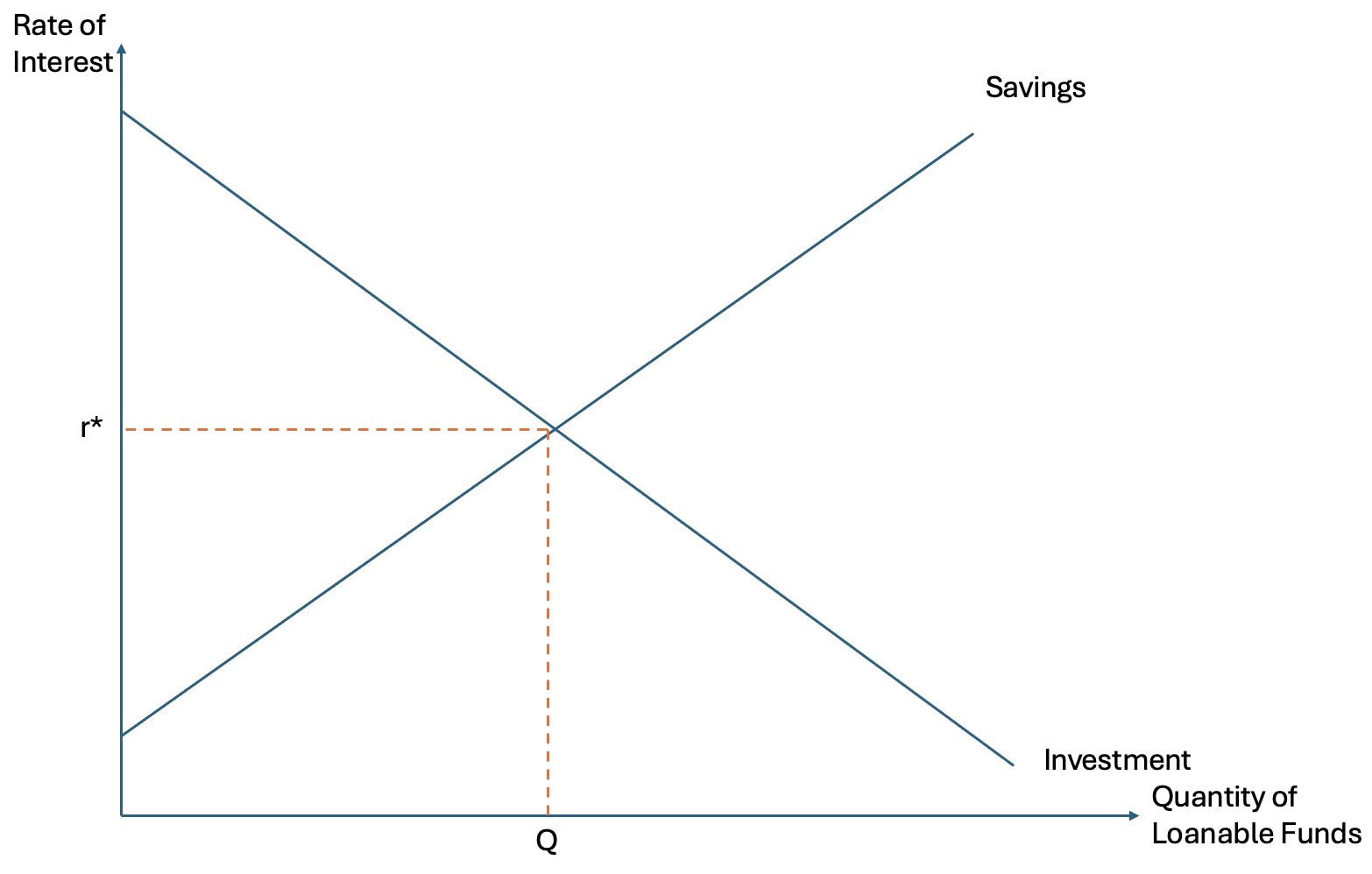

An alternative way of understanding interest rates is through the market for loanable funds. In this framework, the interest rate is determined by the interaction between saving and investment. Households supply loanable funds through saving, while firms demand loanable funds to finance investment.

The supply of loanable funds is positively related to the interest rate, as higher interest rates encourage saving. The demand for loanable funds is negatively related to the interest rate, as higher borrowing costs discourage investment. The equilibrium interest rate equates saving and investment.

This approach emphasizes real factors such as productivity, preferences, and expectations. It also highlights the role of interest rates in allocating resources between present and future consumption.

The interest rate and the central bank

In practice, the central bank plays a central role in influencing interest rates. By setting policy rates and using monetary tools, the central bank affects short term interest rates and influences broader financial conditions. Changes in policy rates affect borrowing costs, asset prices, and spending decisions throughout the economy.

While the central bank cannot fully control all interest rates, its actions shape expectations and guide market outcomes. Through its influence on money supply and financial conditions, the central bank uses interest rates as a key tool for stabilizing inflation and economic activity.