Macroeconomics Chapter 2: Aggregate Supply and Interaction of Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply

This chapter explores the concept of aggregate supply and the interaction of aggregate supply and aggregate demand.

Introduction to Aggregate Supply

Aggregate supply refers to the total quantity of goods and services that firms in an economy are willing and able to produce over a given period of time at different overall price levels. While aggregate demand focuses on total planned expenditure in the economy, aggregate supply focuses on total production. Together, aggregate demand and aggregate supply determine the level of output and the overall price level in the economy.

The quantity of output supplied in an economy depends fundamentally on the quantity of factors of production employed. These factors of production include labour, which is rewarded with wages, land, which is rewarded with rent, capital, which is rewarded with interest or dividends, and enterprise, which is rewarded with profit. The total availability of these factors, and the way in which they are combined in production, determines how much output firms can produce.

Aggregate supply is not simply the sum of individual supply curves from separate markets. In microeconomics, an increase in price may lead firms to switch resources from one market to another in pursuit of higher profits. At the macroeconomic level, this logic does not apply in the same way, because all markets are interrelated. What matters is the relationship between the overall price level in the economy and the total amount of output firms are willing to supply.

In analysing aggregate supply, it is essential to distinguish between the short run and the long run. The behaviour of firms, the flexibility of inputs, and the responsiveness of output to changes in the price level differ markedly between these two time horizons. As a result, economists analyse short-run aggregate supply and long-run aggregate supply separately.

Short-Run Aggregate Supply

Short-run aggregate supply describes the relationship between the overall price level and the quantity of output firms are willing to supply in the short run. In the short run, firms face constraints that limit their ability to adjust production fully in response to changes in demand or prices.

In the short run, some inputs to production are fixed. Firms may have limited ability to change the amount of capital they use, such as machinery, buildings, or transport equipment. Money wages are also likely to be fixed in the short run due to contracts or institutional arrangements. In addition, some raw materials may be in limited supply. These constraints mean that firms cannot instantly adjust all aspects of production.

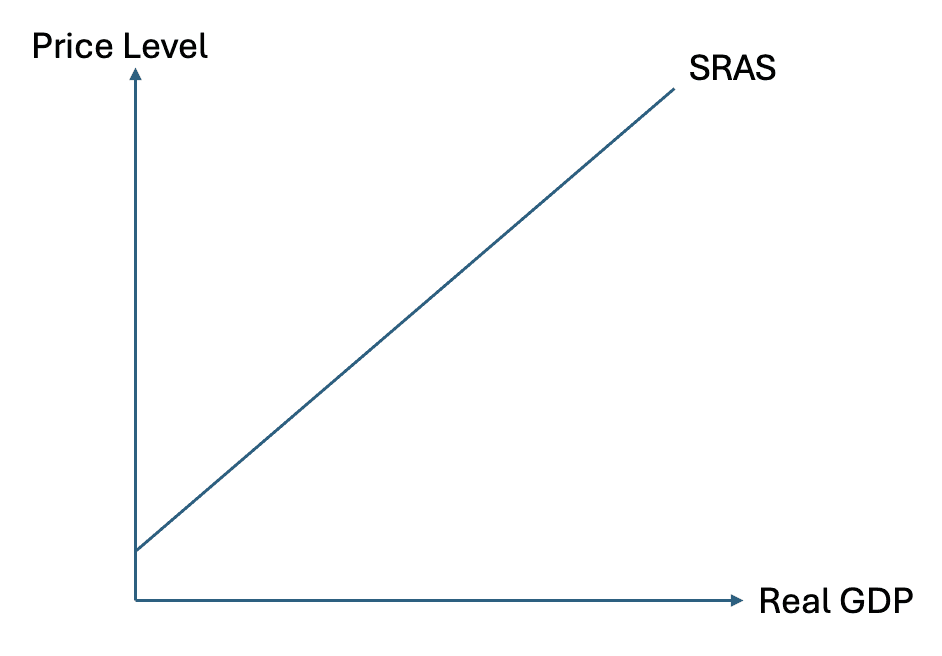

Because of these constraints, short-run aggregate supply is upward sloping. This means that, as the overall price level rises, firms are willing to supply a greater quantity of output. The reason lies in firms’ profit-maximising behaviour. Firms choose output levels that maximise profits, given their costs of production and the prices they receive for their output.

When the overall price level increases, firms receive higher prices for the goods and services they sell. In the short run, many of their costs, particularly wages and the cost of fixed capital, do not rise immediately. As a result, higher prices increase firms’ profitability. This provides an incentive for firms to increase output, even if doing so involves higher marginal costs due to diminishing returns to variable inputs such as labour.

The upward slope of the short-run aggregate supply curve therefore reflects the relationship between rising prices and firms’ willingness to expand production in the presence of fixed inputs and rising marginal costs.

Short-run aggregate supply depends on several key factors that influence firms’ costs of production. One important factor is the state of technology and the effectiveness with which factors of production are used. In the short run, technology tends to change only gradually, so it is usually treated as given. Similarly, the total supply of factors of production is largely fixed in the short run.

However, input prices can change more rapidly. Changes in wages, raw material prices, and energy costs directly affect firms’ costs of production and therefore influence how much output firms are willing to supply at any given price level.

The Cost of Inputs and Short-Run Aggregate Supply

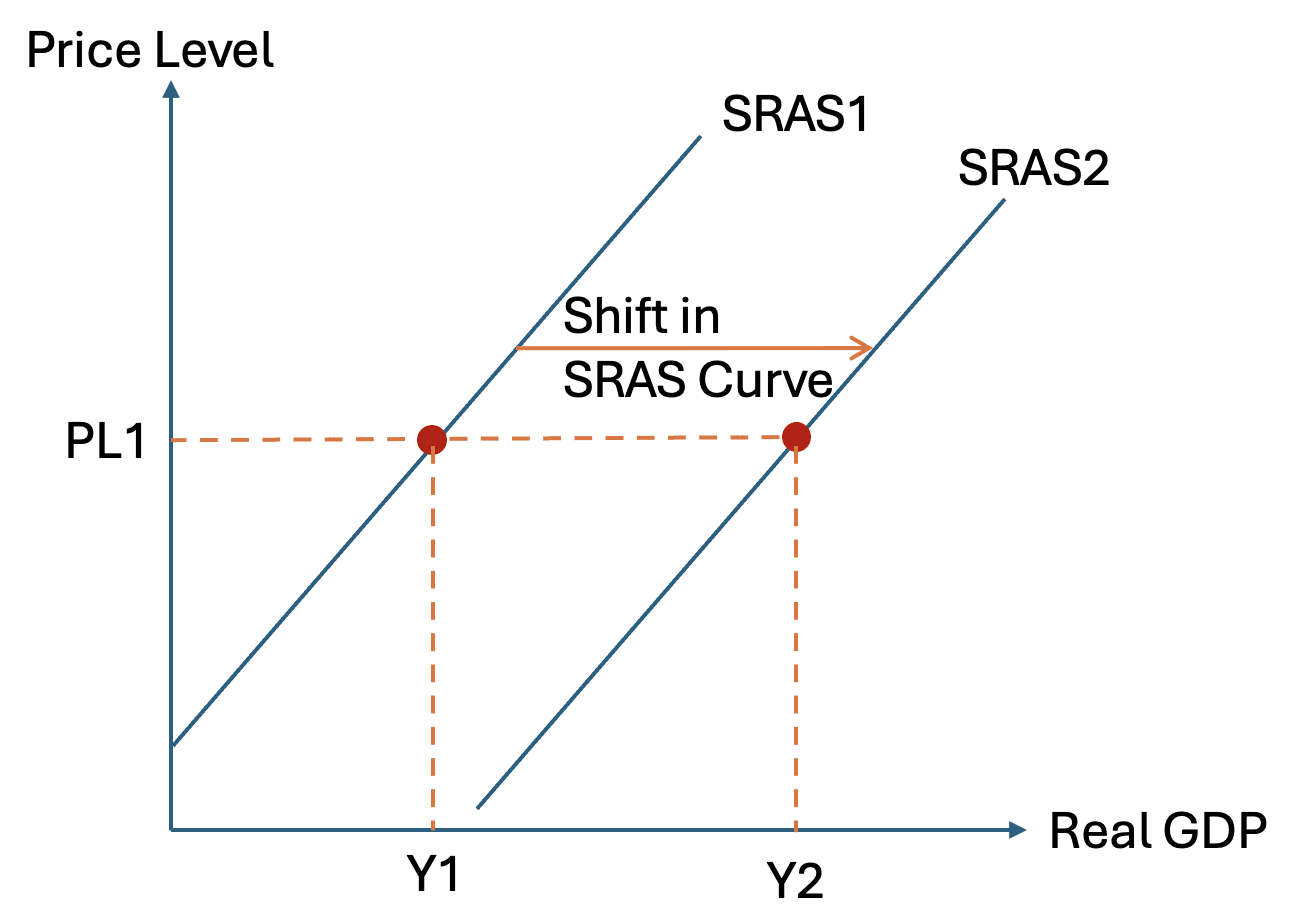

The position of the short-run aggregate supply curve is strongly influenced by the costs firms face in production. If production costs increase, firms will be willing to supply less output at any given overall price level. If production costs fall, firms will be willing to supply more output at any given price level.

One important source of cost changes is the price of raw materials. If a key raw material becomes more expensive due to limited supply, firms’ costs of production rise. To maintain profitability, firms may reduce output at existing prices. This causes the short-run aggregate supply curve to shift to the left.

Energy prices are particularly important in this context. Many industries rely heavily on energy for production, transport, and distribution. An increase in the price of oil, for example, raises costs across a wide range of sectors. This can have a significant impact on short-run aggregate supply by increasing firms’ costs and reducing output at any given price level.

Labour costs are another key determinant of short-run aggregate supply. An increase in wages raises firms’ costs of production. If wages rise faster than productivity, firms’ profit margins are squeezed, and they may reduce output. This again leads to a leftward shift of the short-run aggregate supply curve.

The Exchange Rate and Short-Run Aggregate Supply

For firms that rely on imported inputs, changes in the exchange rate can affect production costs. If the domestic currency appreciates, imported raw materials and components become cheaper in domestic currency terms. This reduces firms’ costs and may allow them to increase output at any given price level, shifting the short-run aggregate supply curve to the right.

If the domestic currency depreciates, imported inputs become more expensive. This raises firms’ costs of production and reduces the quantity of output supplied at any given price level. In this case, the short-run aggregate supply curve shifts to the left.

Because exchange rates can change relatively quickly, they can be an important source of short-run fluctuations in aggregate supply.

Government Intervention and Short-Run Aggregate Supply

Government policies can also affect firms’ costs in the short run. Regulations that require firms to spend more on health and safety measures, environmental protection, or compliance procedures can raise production costs. Higher costs reduce firms’ willingness to supply output at existing prices, shifting the short-run aggregate supply curve to the left.

Changes in taxation can have similar effects. An increase in corporation tax raises the cost of doing business and may reduce firms’ incentives to produce, while a reduction in corporation tax may increase profitability and encourage higher output.

Long-Run Aggregate Supply

While short-run aggregate supply focuses on firms’ responses to price changes when some inputs are fixed, long-run aggregate supply examines how much output an economy can produce when all factors of production are fully flexible. The long run is a period of time sufficient for firms to adjust all inputs, including capital, technology, and labour arrangements.

Long-run aggregate supply refers to the level of output that an economy can sustain when it is making full use of its available factors of production. In this context, full use does not mean that every worker is employed at every moment, but that the economy is operating at a level consistent with full employment of labour and full utilisation of capital, given existing institutions and technology.

A key concept underlying long-run aggregate supply is full employment. Full employment occurs when all factors of production are being used to their full productive capacity. At this level of output, firms are producing as much as they sustainably can, given the available supply of labour, land, capital, and enterprise. The level of output corresponding to full employment is often referred to as the natural level of output.

The Neoclassical View of Long-Run Aggregate Supply

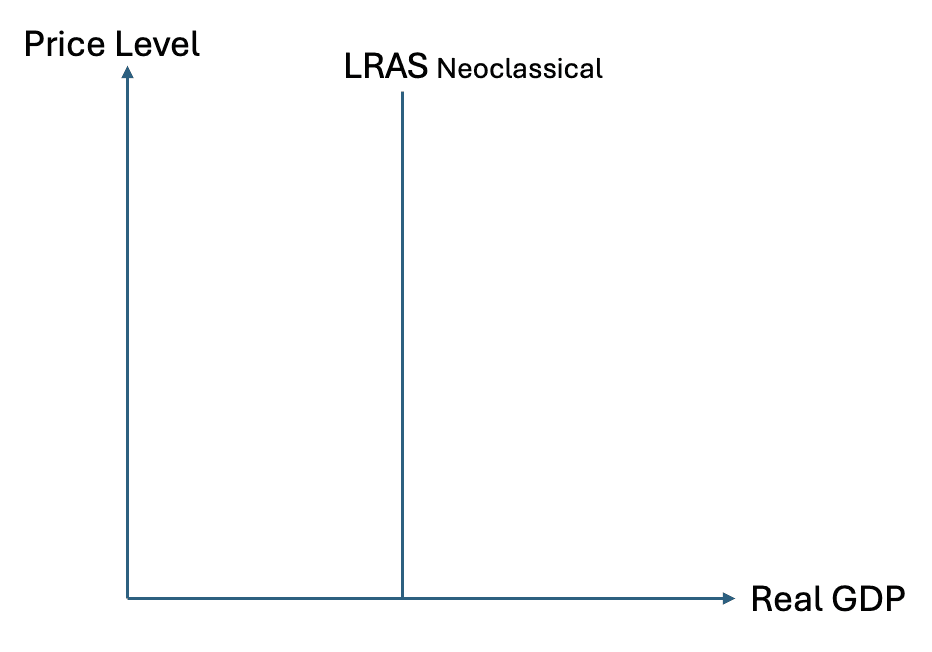

Under the neoclassical view, the long-run aggregate supply curve is vertical at the full employment level of output.

In this representation, the vertical axis shows the overall price level, and the horizontal axis shows real output. The long-run aggregate supply curve is drawn as a vertical line at the level of output corresponding to full employment. This indicates that, in the long run, the quantity of output supplied is independent of the overall price level.

The reasoning behind this view is that, in the long run, prices and wages are fully flexible. If aggregate demand increases, firms initially respond by increasing output. However, as demand continues to rise, competition for factors of production pushes up wages and other input prices. Rising costs eventually eliminate any incentive to produce more output, and firms return to the full employment level of output. The result is a higher price level rather than a permanently higher level of real output.

Similarly, if aggregate demand falls, firms may reduce output in the short run. Over time, falling demand leads to downward pressure on wages and other costs. As costs fall, firms regain profitability and output returns to the full employment level. Again, the adjustment occurs through prices rather than output.

Under this view, the economy is self-correcting in the long run. Deviations from full employment are temporary, and there is no need for policy intervention to restore full employment. Long-run aggregate supply is therefore not sensitive to changes in the price level.

The Keynesian View of Long-Run Aggregate Supply

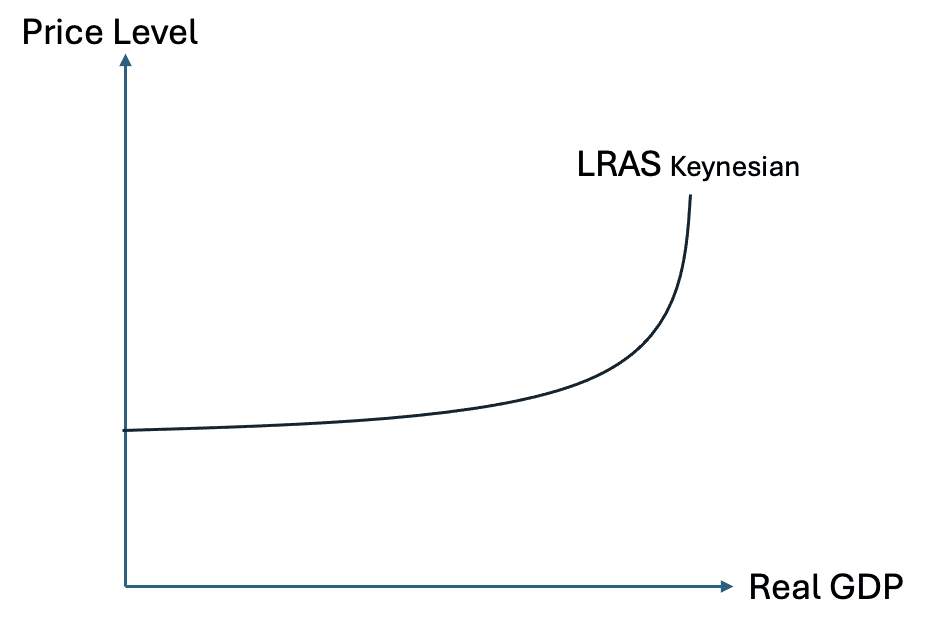

An alternative view, often associated with Keynesian economics, challenges the idea that the economy always returns quickly to full employment. According to this view, the long-run aggregate supply curve may not be vertical across all levels of output.

Under Keynesian assumptions, the economy may settle at an equilibrium level of output below full employment. This occurs because wages and prices may be slow to adjust downward, particularly in labour markets. As a result, insufficient aggregate demand can persist, leaving the economy operating below its productive capacity.

In this representation, long-run aggregate supply is upward sloping over a range of output levels below full employment. At low levels of output, firms are able to increase production without significant increases in costs because there are unemployed resources available. As output rises and spare capacity is reduced, costs begin to rise more rapidly, and the aggregate supply curve becomes steeper.

Once full employment is reached, further increases in demand lead only to higher prices, and long-run aggregate supply becomes vertical. This means that under Keynesian assumptions, the economy may operate for extended periods below full employment, and output is sensitive to changes in aggregate demand over that range.

This view implies that policy intervention may be necessary to increase aggregate demand and move the economy toward full employment.

Shifts in the Long-Run Aggregate Supply Curve

The position of the long-run aggregate supply curve depends on the productive capacity of the economy. Any factor that increases or decreases the economy’s ability to produce goods and services will shift long-run aggregate supply.

One key determinant is the quantity of factor inputs available. An increase in the labour force increases the economy’s productive capacity and shifts long-run aggregate supply to the right. This may occur through population growth, increased labour force participation, or migration. A decrease in the labour force shifts long-run aggregate supply to the left.

Capital accumulation is another important factor. Investment by firms increases the stock of capital available for production. As capital increases, firms are able to produce more output at any given price level, shifting long-run aggregate supply to the right. A decline in investment slows capital accumulation and can limit growth in productive capacity.

The effectiveness with which factors of production are used also affects long-run aggregate supply. Improvements in education and training raise labour productivity. Advances in technology allow firms to produce more output from the same inputs. Better organisation and management can also improve efficiency. All of these factors increase productive capacity and shift long-run aggregate supply to the right.

Government policies can influence long-run aggregate supply by affecting incentives, education, infrastructure, and innovation. Policies that improve the efficiency of labour markets, support skill development, or encourage investment can raise productive capacity over time.

Macroeconomic Equilibrium in the Long Run

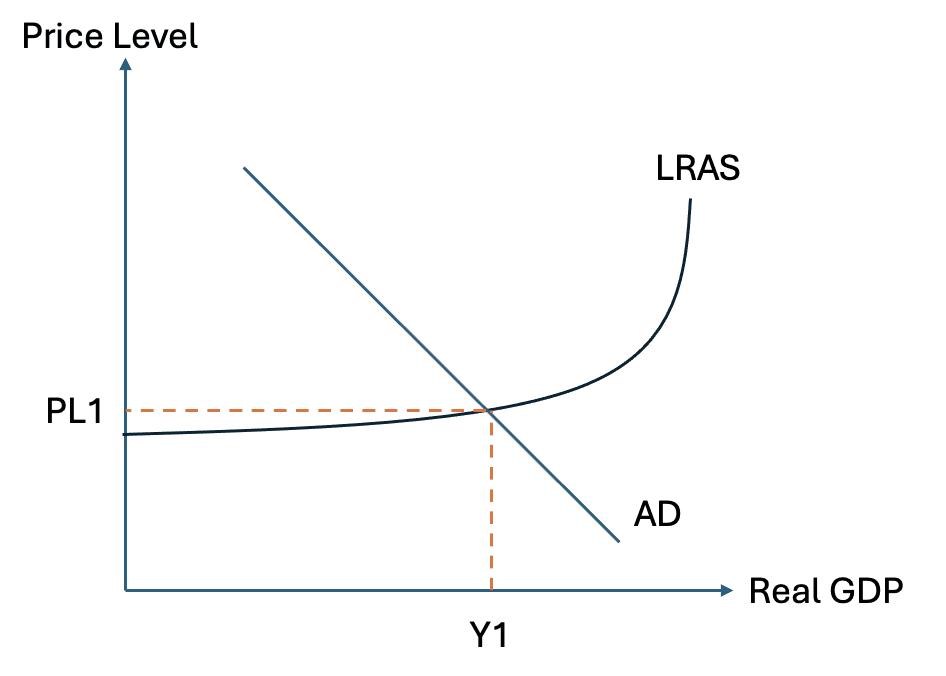

Macroeconomic equilibrium occurs where aggregate demand intersects aggregate supply. In the long run, equilibrium depends on the interaction between aggregate demand and long-run aggregate supply.

Under neoclassical assumptions, equilibrium real output in the long run is determined by the vertical long-run aggregate supply curve. Changes in aggregate demand affect only the price level, not real output. Under Keynesian assumptions, equilibrium output may be below full employment if aggregate demand is insufficient, and policy measures may be required to raise demand.

Understanding long-run aggregate supply is essential for analysing economic growth, unemployment, and inflation. It provides the foundation for examining how economies adjust over time and how policy choices affect long-term outcomes.

Macroeconomic Equilibrium in the Short Run

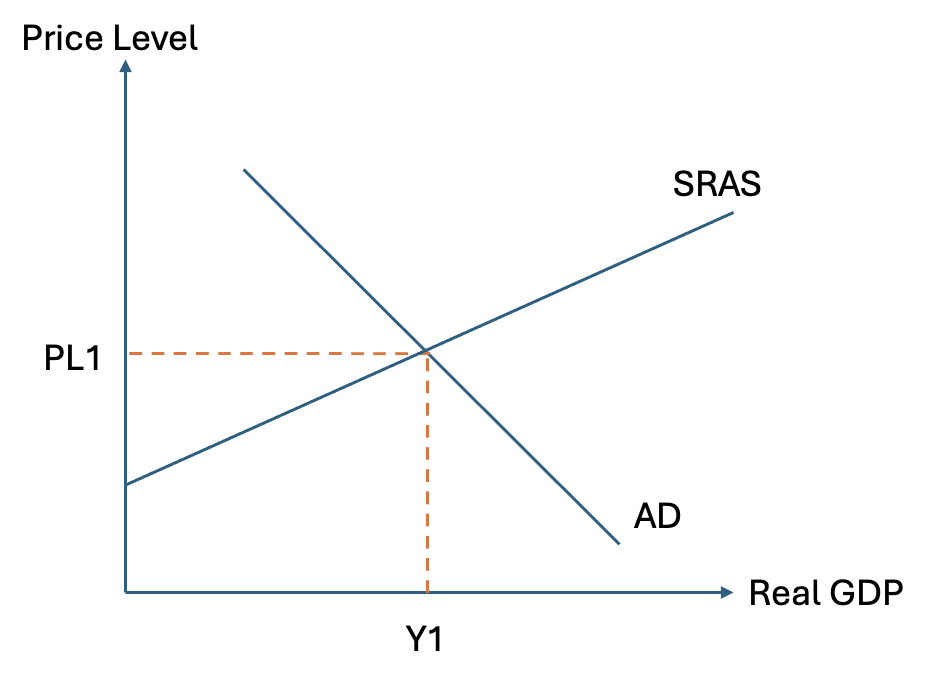

Macroeconomic equilibrium in the short run occurs at the point where aggregate demand intersects short-run aggregate supply. At this point, the quantity of goods and services that firms plan to supply is equal to the quantity that households, firms, the government, and overseas buyers plan to demand. There is therefore no tendency for output or prices to change unless one of the underlying determinants shifts.

In the diagram, the vertical axis represents the overall price level, and the horizontal axis represents real output. The aggregate demand curve slopes downward, reflecting the inverse relationship between the price level and total planned expenditure. The short-run aggregate supply curve slopes upward, reflecting firms’ profit-maximising behaviour in the presence of fixed inputs and rising marginal costs. The intersection of these two curves determines the short-run equilibrium level of real output and the equilibrium price level.

At this equilibrium, firms are able to sell all the output they choose to produce at the prevailing price level. Households and other economic agents are able to purchase the amount of goods and services they plan to buy. There is no excess demand and no excess supply in the economy as a whole.

However, short-run equilibrium does not necessarily correspond to full employment. The equilibrium level of output may be below, equal to, or above the level of output associated with full employment. This depends on the position of aggregate demand relative to the economy’s productive capacity.

If aggregate demand intersects short-run aggregate supply at a level of output below full employment, the economy is operating with spare capacity. In this situation, there is unemployment of labour and underutilisation of capital. Firms are producing less than they could if all resources were fully employed.

If aggregate demand intersects short-run aggregate supply at the full employment level of output, the economy is operating at its sustainable capacity. In this case, all factors of production are fully employed, and output cannot be increased without generating upward pressure on costs and prices.

If aggregate demand intersects short-run aggregate supply at a level of output above full employment, the economy is operating beyond its sustainable capacity. Firms may be relying on overtime, intensive use of capital, or temporary measures to meet high demand. While this may be possible in the short run, it is not sustainable in the long run and will lead to rising costs and inflationary pressure.

Adjustment Towards Long-Run Equilibrium

The short-run equilibrium is not necessarily stable in the long run. Over time, adjustments in wages, input prices, and expectations cause the economy to move toward a long-run equilibrium position.

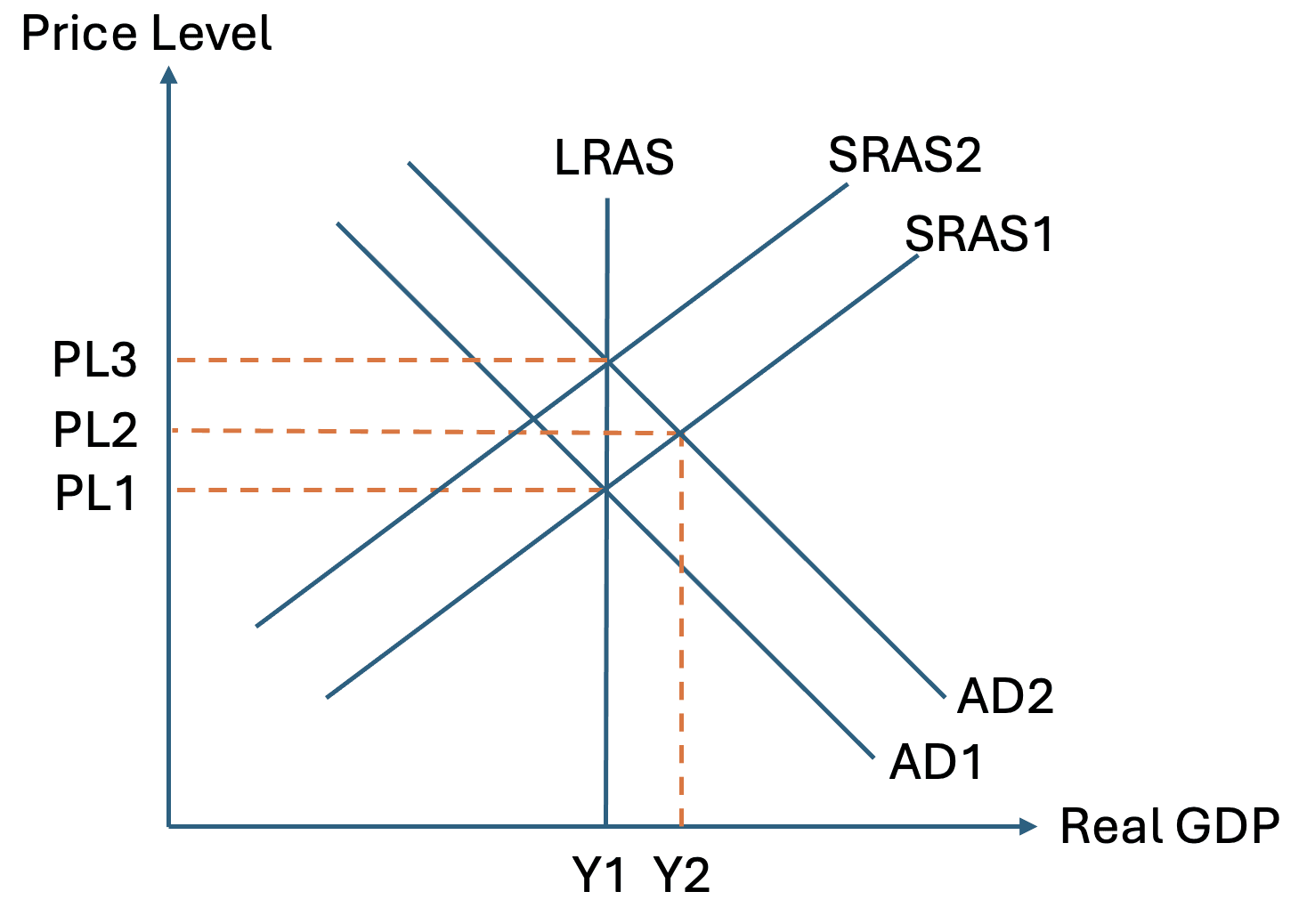

Suppose the economy is initially in short-run equilibrium at a level of output above full employment. Firms are producing more than the economy’s normal capacity. Labour markets are tight, and firms compete for workers by offering higher wages. As wages rise, firms’ costs of production increase. Higher costs reduce profitability at any given price level, leading firms to reduce output.

This process is represented by a leftward shift of the short-run aggregate supply curve. As short-run aggregate supply shifts left, the equilibrium level of output falls and the price level rises. This adjustment continues until output returns to the full employment level, where long-run aggregate supply is located.

Conversely, if the economy is initially in short-run equilibrium below full employment, there is excess capacity and unemployment. Over time, downward pressure may be placed on wages and other input costs. As costs fall, firms find it profitable to increase output at existing prices. This causes the short-run aggregate supply curve to shift to the right.

As short-run aggregate supply shifts right, output increases and the price level falls. The adjustment continues until output reaches the full employment level, assuming wages and prices are sufficiently flexible.

This adjustment mechanism illustrates how short-run fluctuations in output can occur even though long-run output is constrained by productive capacity.

Changes in Aggregate Supply

Changes in aggregate supply can also disturb macroeconomic equilibrium. A negative supply shock occurs when firms’ costs increase, reducing the quantity of output supplied at any given price level.

Examples include sharp increases in energy prices, higher wage costs, or tighter regulations that raise production costs. When short-run aggregate supply shifts to the left, the economy experiences a higher price level and lower real output. This combination of rising prices and falling output presents a challenge for policymakers.

A positive supply shock occurs when firms’ costs fall, or productivity improves. In this case, short-run aggregate supply shifts to the right, leading to higher output and a lower price level.

The impact of supply shocks on the economy depends on whether they are temporary or permanent. Temporary shocks affect short-run aggregate supply, while permanent changes in productivity or factor availability shift long-run aggregate supply.

Stability in Prices, Full Employment, and Economic Growth

The aggregate demand and aggregate supply framework provides a way to understand how the economy achieves equilibrium and how this equilibrium relates to key macroeconomic objectives. Among the most important of these objectives are stability in prices, full employment, and economic growth. Each of these outcomes can be analysed using the AD and AS curves and their interaction over time.

Stability in Prices

Price stability refers to a situation in which the overall price level in the economy does not experience large or unpredictable changes. In the AD and AS model, the equilibrium price level is determined at the point where aggregate demand intersects aggregate supply.

When the economy is operating at full employment, an increase in aggregate demand leads primarily to an increase in the price level rather than an increase in real output. This occurs because the economy is already using its factors of production fully. Firms cannot increase output without bidding up wages and other input prices, which raises costs and leads to higher prices.

In this situation, continued increases in aggregate demand generate inflation. As aggregate demand shifts further to the right, the price level continues to rise. Real output remains unchanged in the long run because it is constrained by productive capacity. The AD and AS model therefore explains why demand driven inflation occurs when an economy is at or close to full employment.

Price instability can also arise from changes in aggregate supply. A negative supply shock, such as an increase in energy prices or a rise in production costs, shifts the short-run aggregate supply curve to the left. This leads to a higher price level and lower real output. In this case, inflation is driven by rising costs rather than excess demand.

The AD and AS model shows that maintaining price stability requires an economy to avoid persistent excess demand and large adverse supply shocks. It also highlights the difficulty of responding to supply side inflation, where reducing inflation may involve accepting lower output in the short run.

Full Employment

Full employment is achieved when the economy is producing at its full employment level of output. At this level, all factors of production are being used efficiently, and unemployment is limited to frictional and structural forms that exist even in a healthy labour market.

In the AD and AS framework, full employment corresponds to the level of output where long-run aggregate supply is located. Under neoclassical assumptions, the long-run aggregate supply curve is vertical at this level of output. This implies that the economy naturally returns to full employment as wages and prices adjust.

If aggregate demand is initially insufficient, the economy may settle at a short-run equilibrium below full employment. In this situation, there is spare capacity and unemployment. Under neoclassical assumptions, falling wages and costs eventually restore profitability and shift short-run aggregate supply to the right, returning output to the full employment level.

Under Keynesian assumptions, wages and prices may not adjust quickly downward. As a result, the economy may remain below full employment for an extended period. In this case, an increase in aggregate demand may be required to move the economy toward full employment. The AD and AS model therefore allows for different interpretations of how full employment is restored and whether policy intervention is necessary.

Economic Growth

Economic growth refers to an increase in the economy’s capacity to produce goods and services over time. In the AD and AS framework, long run economic growth is represented by a rightward shift of the long-run aggregate supply curve.

A shift in long-run aggregate supply occurs when the productive capacity of the economy increases. This can result from an increase in the quantity of factors of production or from improvements in the effectiveness with which those factors are used.

An increase in the labour force, such as through population growth or migration, raises the economy’s capacity to produce output. This shifts long-run aggregate supply to the right. Similarly, an increase in the stock of capital through sustained investment expands productive capacity and shifts long-run aggregate supply outward.

Improvements in education, training, and skills raise labour productivity and allow the economy to produce more output with the same number of workers. Advances in technology improve the efficiency of both labour and capital, further increasing productive capacity. These changes also shift long-run aggregate supply to the right.

In the AD and AS model, economic growth allows the economy to achieve higher levels of real output without generating inflationary pressure. When long-run aggregate supply increases, the economy can support higher aggregate demand while maintaining price stability.

Using the AD and AS Model to Analyse Change

The AD and AS model allows economists to analyse how changes in demand and supply affect equilibrium output and prices over time. By identifying whether a shock affects aggregate demand or aggregate supply, and whether it is temporary or permanent, the likely adjustment path of the economy can be traced.

Movements along the AD and AS curves occur when the price level changes. Shifts of the curves occur when underlying determinants change. Distinguishing between these two types of change is essential for accurate analysis.

The model also highlights the trade offs that may arise between different macroeconomic objectives. Policies aimed at stimulating demand may reduce unemployment but increase inflation. Policies aimed at reducing inflation may slow output growth in the short run. Understanding these trade offs is a central task of macroeconomic analysis.