Macroeconomics Chapter 4: Policy Objectives - Economic Growth

This chapter explores the concept of short run and long run economic growth, its causes and implications.

What Is Economic Growth

Economic growth refers to an increase in the productive capacity of an economy and the level of output it is able to produce over time. From an economic perspective, growth matters because it expands the resources available to society and therefore makes it possible to improve material living standards.

Economic growth can be understood in two distinct but related ways, depending on whether the focus is on actual output or potential output.

Long-run economic growth refers to an expansion of the productive capacity of an economy. This means that the economy becomes capable of producing a greater quantity of goods and services than before. In other words, the maximum sustainable level of output increases. This is equivalent to an outward movement of the economy’s production possibility curve. When long-run growth occurs, the economy can produce more of all goods, not because resources are being used more intensively, but because the quantity or productivity of resources has increased.

Short-run economic growth refers to an increase in actual output, measured by real gross domestic product, over a given period of time. This type of growth can occur even if the productive capacity of the economy has not changed. For example, if the economy is operating below full employment and unused resources exist, output can rise as these resources are brought into use. In this case, growth reflects better utilisation of existing factors of production rather than an expansion of productive capacity.

It is important to distinguish clearly between these two concepts. An economy may experience short-run growth without any increase in its long-run capacity to produce. Conversely, long-run growth may take place even if short-run output fluctuates due to cyclical conditions.

Economic Growth and the Production Possibility Curve

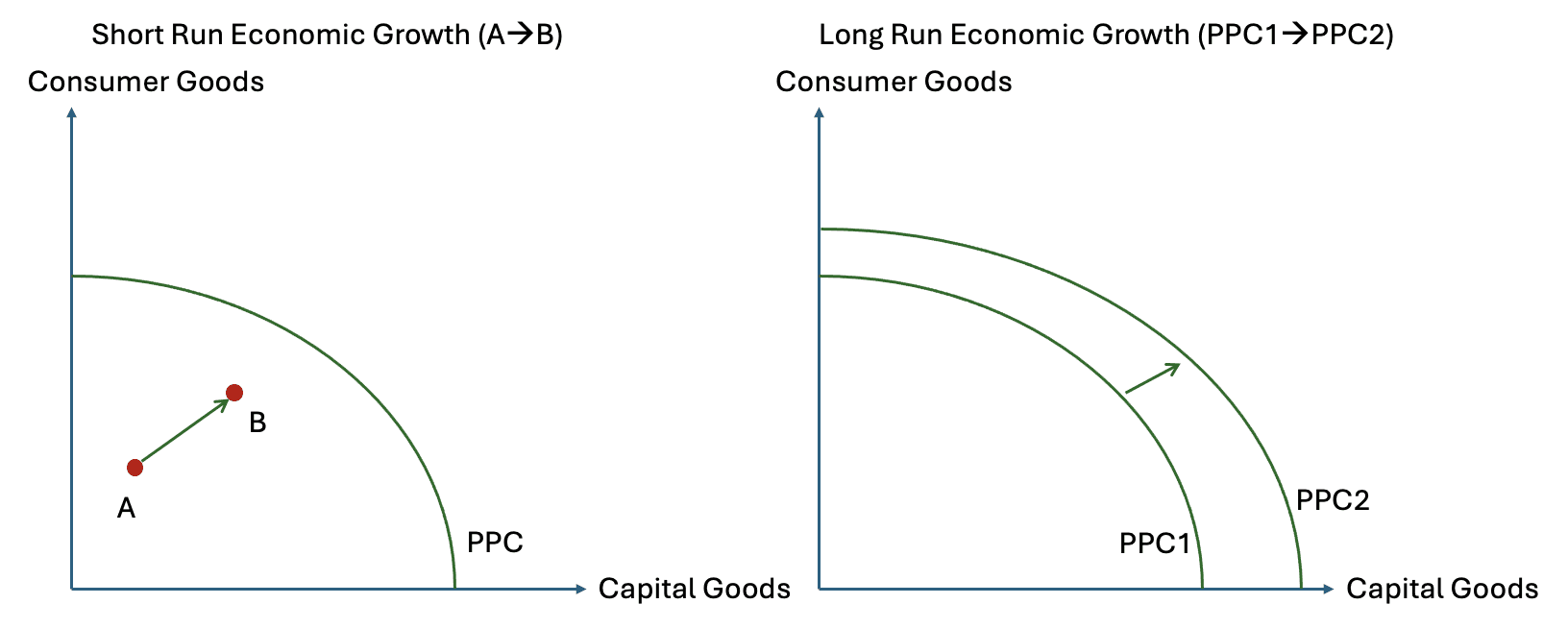

The distinction between short-run and long-run economic growth can be illustrated using the production possibility curve.

The production possibility curve shows the maximum combinations of two types of goods that an economy can produce when all resources are fully employed and used efficiently. Any point on the curve represents full employment. Points inside the curve represent underutilisation of resources, while points outside the curve are unattainable given current resources and current technology.

Short-run economic growth can be represented as a movement from a point inside the production possibility curve toward the curve itself. This occurs when previously unemployed or underutilised resources are brought into productive use. For example, a fall in unemployment allows output to increase without any change in the economy’s capacity. In this case, the production possibility curve itself does not shift.

Long-run economic growth is represented by an outward shift of the production possibility curve. This indicates that the economy’s productive capacity has increased. The economy can now produce more of both goods than before at full employment. Such a shift reflects changes such as an increase in the labour force, an expansion of the capital stock, or improvements in productivity.

Measuring Economic Growth Using GDP

In practice, economic growth is measured using gross domestic product. Gross domestic product measures the total output of goods and services produced within an economy over a given period of time. Growth is measured not by the level of GDP itself, but by the rate at which real GDP changes over time.

Real GDP measures output at constant prices, removing the effects of inflation. This is essential because an increase in nominal GDP could simply reflect higher prices rather than an increase in actual output. Economic growth is therefore defined as the percentage change in real GDP over a given period.

When economists refer to growth figures reported by statistical agencies, they are referring to changes in real GDP. These figures capture changes in the quantity of goods and services produced and therefore provide an indication of changes in economic activity.

However, it is important to recognise that measured growth in GDP does not always correspond directly to changes in productive capacity. Growth in real GDP may reflect short-run movements toward or away from full employment rather than long-run growth. For this reason, economists often distinguish between actual growth and potential growth.

Economic Growth and Long-Run Aggregate Supply

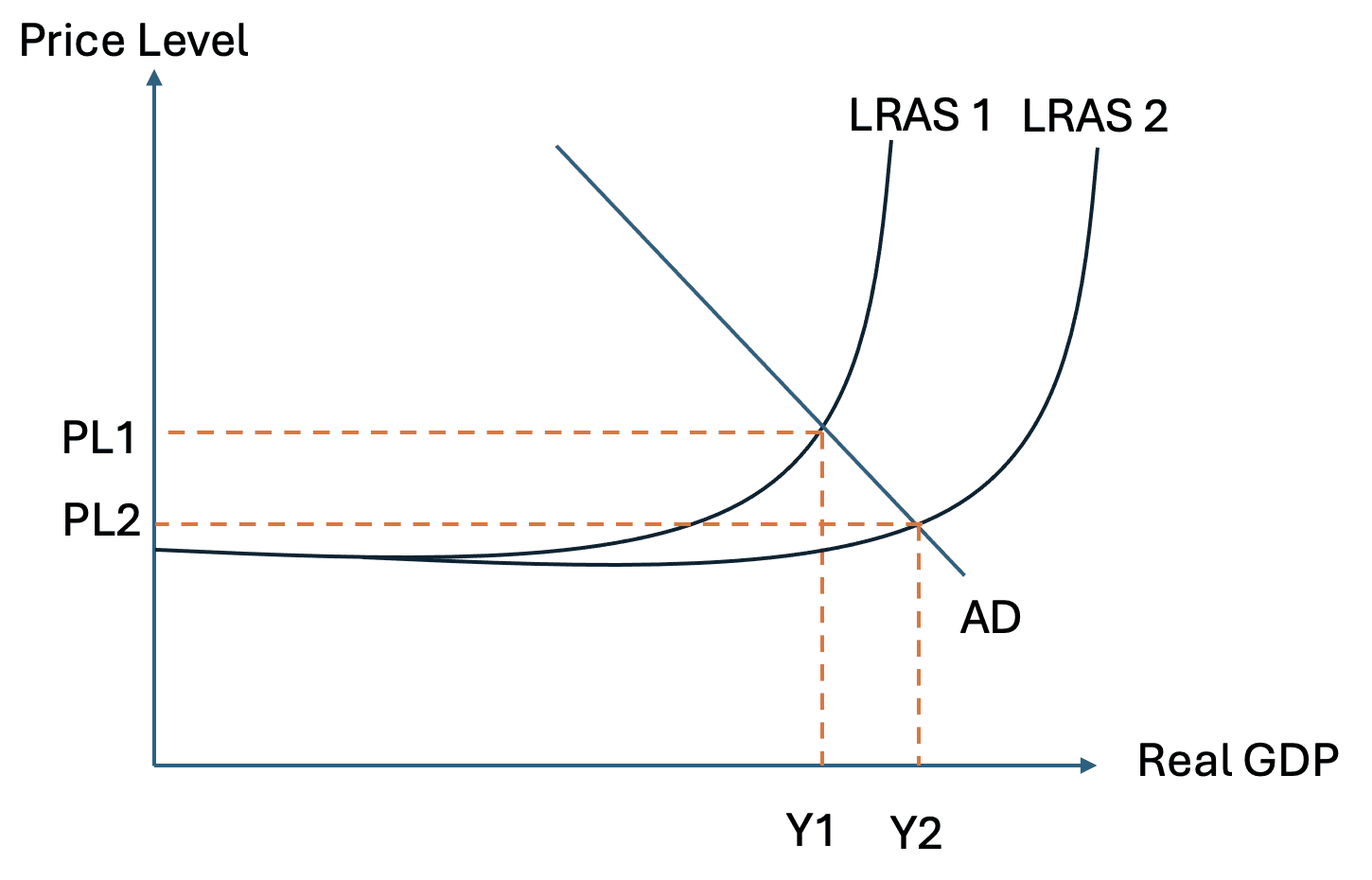

Long-run economic growth can also be shown using the aggregate demand and aggregate supply framework.

In this framework, long-run aggregate supply represents the full employment level of output. An increase in productive capacity is shown as a rightward shift of the long-run aggregate supply curve. This shift indicates that the economy can produce a higher level of real GDP at full employment.

When long-run aggregate supply increases, the full employment level of output rises. Depending on the position of aggregate demand, this may also be associated with changes in the price level. Under neoclassical assumptions, an increase in long-run aggregate supply leads primarily to an increase in output rather than sustained inflation.

The AD–AS model therefore provides a complementary way of analysing long-run economic growth alongside the production possibility curve.

The Policy Objective of Economic Growth

Economic growth is widely regarded as a central objective of macroeconomic policy because it enables improvements in living standards over time. When an economy’s productive capacity expands, it becomes possible to produce a greater quantity of goods and services. This expansion increases the resources available to society and allows for higher levels of consumption, improved public services, and greater economic security.

In industrial economies, populations have come to expect rising incomes and improving material conditions. Economic growth supports these expectations by allowing real incomes to increase without requiring redistribution between groups. When output grows, it becomes easier to raise living standards across the population without creating conflicts over limited resources.

For policymakers, the expansion of productive capacity is therefore seen as a fundamental objective. Economic performance is often assessed in terms of the economy’s ability to grow over time, which explains why growth figures are closely monitored and widely reported.

Economic growth is also linked to other macroeconomic objectives. Stable growth facilitates employment creation, as expanding output generally requires more labour. Higher employment supports household incomes and reduces the social costs associated with unemployment. Growth also strengthens public finances, as higher output and incomes generate greater tax revenues. These revenues can be used to finance public services such as healthcare, education, and infrastructure.

Because of these connections, other policy objectives are often seen as supportive of growth rather than as ends in themselves. For example, controlling inflation is important because price instability can undermine investment and reduce the efficiency of resource allocation. Maintaining high employment is important because idle resources represent lost output and lost growth potential. In this sense, growth acts as an overarching objective that other policies are designed to support.

However, the pursuit of economic growth is not without limitations. Growth in output does not automatically translate into equal improvements in living standards across the population. If the gains from growth are unevenly distributed, some groups may benefit far more than others. In such cases, growth may be accompanied by rising inequality, which can create social and economic tensions.

Furthermore, an exclusive focus on maximising GDP growth may overlook other aspects of well-being. Economic activity that increases measured output may also generate costs, such as environmental damage or congestion, which reduce quality of life. These considerations suggest that while economic growth is an important policy objective, it is not the only measure of economic success.

The Importance of Data

To monitor the performance of an economy and to assess whether economic growth is taking place, it is essential to rely on economic data. Without systematic measurement, it would be impossible to determine whether output is increasing, stagnating, or falling, or to judge whether policy objectives are being met.

Economics, and macroeconomics in particular, is largely a non-experimental discipline. Economists cannot conduct controlled experiments on entire economies in the way that natural scientists can conduct laboratory experiments. Instead, economists must observe what happens in the real world and attempt to interpret economic outcomes using available data. This makes the collection and interpretation of economic statistics central to economic analysis.

Most of the data used to measure economic growth are collected and published by government agencies. In the United Kingdom, economic statistics are primarily produced by the Office for National Statistics. In other countries, similar national statistical agencies perform this role. At the international level, organisations such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the United Nations compile and publish economic data to allow comparisons between countries.

The production of reliable economic data is a complex and resource-intensive process. Measuring total output requires information from a vast number of firms, households, and institutions. As a result, data are often published with a time lag and may be subject to later revision as more complete information becomes available. Early estimates of growth are therefore provisional and should be interpreted with caution.

Another difficulty arises from the changing nature of economic activity. As economies evolve, new goods and services emerge while others decline or disappear. Capturing these changes accurately within a consistent statistical framework is challenging. This is particularly relevant in economies where services and digital activities account for a growing share of output.

It is also important to recognise that economic data are collected under conditions where many factors are changing at the same time. The ceteris paribus assumption, which holds other factors constant in order to isolate a single relationship, is rarely satisfied in reality. When interpreting data on economic growth, it is therefore difficult to attribute observed changes to a single cause with certainty.

International comparisons of growth present additional challenges. Differences in data collection methods, price levels, and economic structures mean that comparisons between countries must be treated with care. Even when international organisations attempt to standardise measurements, some degree of imprecision is unavoidable.

Despite these limitations, economic data remain indispensable. They provide the best available means of assessing economic performance, identifying trends, and informing policy decisions. Understanding how data are collected and the constraints under which they are produced is therefore a crucial part of analysing economic growth.

Real and Nominal Measurements

When measuring economic growth, economists must distinguish carefully between changes in output that result from changes in quantities and changes that result from changes in prices. This distinction is captured through the concepts of nominal and real measurements.

Nominal values measure economic variables using current prices, meaning the prices that prevail at the time the transaction takes place. When output is measured in nominal terms, changes in the value of production may reflect changes in quantities produced, changes in prices, or a combination of both. As a result, nominal measurements cannot by themselves provide a reliable indication of whether an economy is producing more goods and services.

Real values adjust nominal measurements to take account of changes in prices over time. By holding prices constant, real measurements isolate changes in quantities produced. This allows economists to determine whether output has genuinely increased rather than simply becoming more expensive.

This distinction is fundamental when analysing economic growth. Growth refers to an increase in real output, not merely an increase in the monetary value of output. An economy in which nominal GDP is rising rapidly may not be experiencing real growth if prices are also rising at a similar or faster rate.

Why Nominal Measures Are Insufficient

Suppose an economy produces the same quantity of goods in two consecutive years, but prices rise between the first year and the second. If output is measured using current prices in each year, the value of output will appear to have increased. However, this increase reflects inflation rather than any change in productive activity.

Using nominal measures alone would therefore overstate economic performance in periods of rising prices. Conversely, during periods of falling prices, nominal measures might understate real growth. This problem makes it impossible to assess changes in output accurately without adjusting for price movements.

For this reason, economists focus on real GDP when measuring economic growth. Real GDP values output at constant prices, allowing comparisons over time that reflect changes in quantities rather than prices.

Constructing Real Values

To convert nominal values into real values, economists use price indices. A price index measures the average level of prices relative to a chosen base year. By comparing current prices to prices in the base year, it is possible to remove the effect of price changes.

Real GDP is calculated by valuing current output using the prices of the base year. This means that the same set of prices is applied across different periods, ensuring that changes in measured output reflect changes in quantities produced.

Statistical agencies use constant price measures to produce real GDP figures. In the United Kingdom, real GDP is measured using chained volume measures. This method updates the base year regularly to improve accuracy and reflect changes in consumption patterns over time.

The use of chained volume measures helps reduce distortions that can arise when relative prices change significantly. However, it also means that real GDP figures may be revised as methods and data improve.

Real GDP and Economic Growth

Economic growth is measured as the percentage change in real GDP over a given period. This focuses attention on changes in actual output rather than changes in prices. The growth rate of real GDP provides an indication of how rapidly the economy’s productive activity is expanding or contracting.

It is important to emphasise that economic growth is not measured by the level of GDP itself, but by the rate at which real GDP changes. A large economy may have a higher level of GDP than a smaller economy but may grow more slowly. Conversely, a smaller economy may experience rapid growth even if its total output remains relatively low.

Because real GDP removes the effects of inflation, it provides a consistent basis for tracking economic performance over time. Without this adjustment, it would be impossible to distinguish between real growth and price-driven increases in output values.

Limitations of Real and Nominal Measures

Although real GDP is essential for measuring economic growth, it is not without limitations. Constructing real values requires accurate price indices, which can be difficult to produce. Changes in quality, the introduction of new goods, and shifts in consumption patterns complicate the task of measuring prices consistently over time.

In addition, real GDP focuses on market activity and excludes non-market production. As a result, changes in real GDP may not fully capture changes in overall economic well-being. Nevertheless, real GDP remains the standard measure used to assess economic growth because it provides the most systematic and widely accepted way of tracking changes in output.

GDP and Growth

Gross domestic product is used to measure the total output of an economy over a given period of time. When economists analyse economic growth, they are interested not in the absolute level of GDP, but in how GDP changes from one period to the next. Economic growth is therefore measured as the rate of change of real GDP.

GDP focuses on production that takes place within the domestic economy. This includes output produced by foreign-owned firms operating within the country but excludes income earned by domestic residents from production abroad. For this reason, GDP measures domestic output rather than domestic income.

Although real GDP provides an indication of the quantity of goods and services produced, it has limitations as a measure of living standards. GDP does not account for how income is distributed across the population, nor does it capture non-market activities. Nevertheless, GDP remains central to the analysis of economic growth because it provides a consistent and measurable indicator of economic activity.

Measuring Growth Rates

To assess economic growth, economists calculate the percentage change in real GDP between one period and the next. This approach focuses on how quickly output is expanding or contracting rather than on the absolute size of the economy.

The percentage change in real GDP is calculated by taking the change in real GDP between two periods, dividing it by the initial level of real GDP, and multiplying by one hundred. This method ensures that growth is measured relative to the size of the economy at the starting point.

Measuring growth in percentage terms allows meaningful comparisons over time and across economies of different sizes. A large economy may experience lower percentage growth than a smaller economy even if the absolute increase in output is greater. The growth rate therefore provides information about the pace of economic expansion rather than its scale.

Fluctuations and the Long-Run Trend

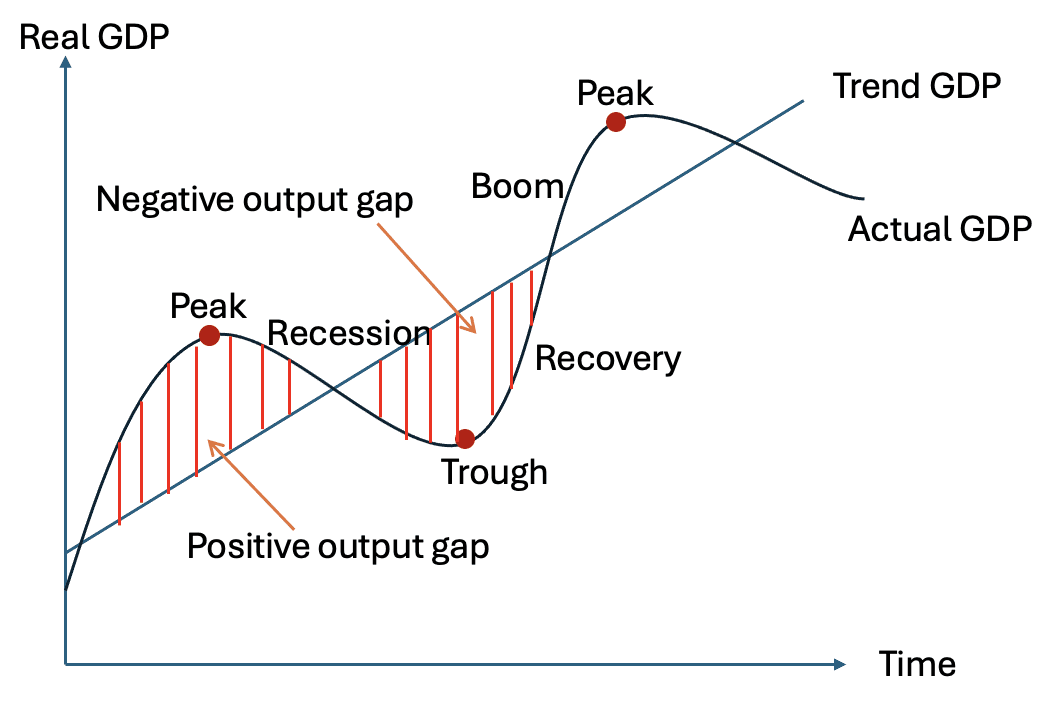

Although economic growth is often discussed in terms of long-run trends, actual GDP does not increase smoothly over time. Instead, GDP tends to fluctuate around an underlying upward trend. These fluctuations reflect changes in aggregate demand, external shocks, and cyclical movements in economic activity.

The trend level of GDP represents the long-run path of output growth, reflecting the expansion of productive capacity over time. Actual GDP may lie above or below this trend at different points. When actual GDP is below the trend, the economy is operating below its potential level of output. When actual GDP is above the trend, the economy is operating above its normal capacity.

These deviations from trend are closely related to the concept of the output gap. A negative output gap occurs when actual GDP lies below the trend level. A positive output gap occurs when actual GDP lies above the trend level.

Volatility in Growth Rates

Year-to-year growth rates can be volatile. Growth may be strong in one year and weak or negative in the next. This volatility makes it difficult to identify the underlying trend in economic growth using short time periods.

For this reason, economists often use averages taken over several years to smooth out short-run fluctuations. A long-run average growth rate provides a clearer indication of the economy’s underlying growth performance.

Periods of recession are characterised by falling real GDP. A recession is commonly defined as a situation in which real GDP falls for two consecutive periods. During recessions, growth rates are negative, and output falls below its trend level.

Recoveries occur when GDP begins to rise again following a recession. However, output may remain below its previous trend for an extended period, indicating a persistent negative output gap.

GDP per Capita

When assessing living standards, it is often more informative to consider GDP per capita rather than total GDP. GDP per capita measures the average level of output per person and is calculated by dividing total GDP by the size of the population.

An increase in total GDP does not necessarily imply an improvement in living standards if population growth is equally rapid. GDP per capita adjusts for population size and provides a better indication of how much output is available, on average, to each individual.

Growth in GDP per capita therefore reflects improvements in average material living standards. However, as with GDP itself, GDP per capita does not account for income distribution and should be interpreted with caution.

Causes of Economic Growth

Economic growth does not occur automatically. It arises from identifiable changes in the way an economy uses its resources and from changes in the quantity and quality of those resources. To analyse growth properly, it is essential to distinguish between short-run causes of growth and long-run causes of growth. These two types of growth differ in both their sources and their implications for the economy.

Short-Run Economic Growth

Short-run economic growth occurs when actual output increases without any change in the economy’s productive capacity. This type of growth reflects improved utilisation of existing resources rather than an expansion of the economy’s maximum potential output.

In the short run, an economy may be operating below full employment. In this situation, labour and capital are underutilised. There may be unemployed workers, idle machinery, or unused factory capacity. When demand increases, firms can respond by employing these unused resources, increasing output without requiring additional capital or new technology.

Short-run growth is therefore closely linked to changes in aggregate demand. An increase in consumption, investment, government expenditure, or exports raises aggregate demand. Firms respond to higher demand by increasing production. As output rises, employment increases, and incomes rise.

In terms of the aggregate demand and aggregate supply framework, short-run growth is represented by a movement along the long-run aggregate supply curve combined with a movement along the short-run aggregate supply curve. The economy moves closer to the full employment level of output without any shift in long-run aggregate supply.

Short-run growth can also be illustrated using the production possibility curve. When the economy is operating inside the curve, an increase in output can occur through better utilisation of existing resources. This appears as a movement from a point inside the curve toward the curve itself. The curve does not shift outward, indicating that productive capacity has not changed.

Short-run growth is often associated with economic recovery following a recession. As confidence improves and demand strengthens, firms increase output and employment. However, once the economy reaches full employment, further growth of this kind is no longer possible.

Limitations of Short-Run Growth

Although short-run growth can raise output and employment, it does not increase the economy’s productive capacity. Once all available resources are fully employed, output cannot increase further without creating inflationary pressure.

At full employment, increases in aggregate demand lead primarily to higher prices rather than higher real output. Firms cannot expand production without bidding up wages and other input prices. As a result, short-run growth has natural limits.

This highlights the importance of long-run economic growth, which allows sustained increases in output without inflation.

Long-Run Economic Growth

Long-run economic growth occurs when the economy’s productive capacity increases. This type of growth is achieved when the economy becomes capable of producing more goods and services at full employment than before.

Long-run growth is represented by an outward shift of the production possibility curve. It can also be shown as a rightward shift of the long-run aggregate supply curve. In both cases, the economy’s maximum sustainable level of output increases.

Long-run economic growth depends on changes in the quantity and quality of factors of production and on improvements in how those factors are combined.

The Role of Labour in Long-Run Growth

An increase in the quantity of labour raises the economy’s productive capacity. This may occur through population growth, higher labour force participation, or migration. When more workers are available, the economy can produce more output, provided that other factors of production are also available.

The quality of labour is equally important. Improvements in education, training, and skills raise labour productivity. When workers are more productive, they can produce more output per hour of work. Higher productivity allows the economy to grow even if the size of the labour force remains unchanged.

Education and training therefore play a central role in long-run growth by increasing the effectiveness of labour as a factor of production.

The Role of Capital in Long-Run Growth

Capital accumulation is a key driver of long-run economic growth. Capital refers to man made productive assets such as machinery, equipment, and buildings. When firms invest, they increase the capital stock available for production.

A larger capital stock allows workers to be more productive. Better machinery and infrastructure enable firms to produce more output using the same amount of labour. This increases the economy’s productive capacity.

Sustained investment is therefore essential for long-run growth. If investment is insufficient to replace worn out capital, the capital stock may stagnate or decline, limiting growth.

The Role of Enterprise and Technology

Enterprise refers to the willingness of individuals to take risks, organise production, and introduce new methods. Enterprise earns profit as its reward. Entrepreneurial activity contributes to growth by identifying new opportunities, improving efficiency, and driving innovation.

Technological progress allows the economy to produce more output from the same inputs. New technologies improve production processes, reduce costs, and increase productivity. Technological change is a major source of long-run growth because it shifts the production possibility curve outward without requiring proportional increases in inputs.

Advances in technology often interact with investment and education. New technologies require new capital and skilled workers to be fully effective. As a result, long-run growth depends on the combined development of capital, labour, and technology.

The Role of Government in Long-Run Growth

Government policies can influence long-run growth by affecting incentives, education, infrastructure, and the institutional framework of the economy. Spending on education and training improves labour productivity. Investment in infrastructure supports private sector production. Policies that encourage investment and innovation can raise productive capacity over time.

However, government intervention can also hinder growth if it reduces incentives to work, invest, or innovate. The impact of policy depends on how it affects behaviour and resource allocation.

Costs and Benefits of Economic Growth

Economic growth is often treated as a desirable outcome because it expands the economy’s capacity to produce goods and services. However, growth also has costs as well as benefits. A balanced evaluation of economic growth requires careful consideration of both sides, rather than assuming that higher growth is always and everywhere beneficial.

Benefits of Economic Growth

One of the main benefits of economic growth is the potential improvement in material living standards. When an economy produces a greater quantity of goods and services, households are able to consume more. Higher output makes it possible for real incomes to rise over time, allowing people to afford better housing, improved nutrition, and access to a wider range of goods and services.

Economic growth also supports higher levels of public spending. As output and incomes rise, tax revenues tend to increase even if tax rates remain unchanged. This provides governments with additional resources to finance public services such as healthcare, education, and transport infrastructure. Improved public services can raise overall well-being and support further growth by improving the productivity of labour and capital.

Growth is closely linked to employment. Expanding output usually requires more labour, particularly when the economy is operating below full employment. As firms increase production, they hire additional workers, reducing unemployment. Higher employment increases household incomes and reduces the social and fiscal costs associated with unemployment.

Economic growth can also increase the economy’s resilience to shocks. A growing economy is better able to absorb negative events such as external demand shocks or financial disturbances. With higher incomes and stronger public finances, governments have more flexibility to respond to downturns without severe reductions in living standards.

In addition, sustained growth can facilitate structural change. As output expands, resources can be reallocated from declining industries to expanding sectors without causing large-scale unemployment. This makes economic adjustment less painful and supports long-term development.

Costs of Economic Growth

Despite these benefits, economic growth can also impose costs. One important cost is environmental damage. Increased production often involves greater use of natural resources and higher levels of pollution. If growth relies heavily on resource extraction or energy-intensive production, it can lead to environmental degradation, loss of biodiversity, and long-term damage to ecosystems.

Environmental costs may not be fully reflected in market prices. As a result, growth measured by GDP may increase even as environmental quality deteriorates. This raises concerns about the sustainability of growth and whether current increases in output are achieved at the expense of future generations.

Economic growth can also be unevenly distributed. In some cases, the gains from growth may accrue mainly to certain groups, regions, or sectors. If income inequality increases alongside growth, some households may see little improvement in living standards even as average GDP rises. This can generate social tensions and reduce the overall benefits of growth.

Rapid growth can also place pressure on infrastructure and public services. Transport systems, housing, healthcare, and education may struggle to keep pace with expanding economic activity. If infrastructure investment does not match the pace of growth, congestion and shortages can reduce quality of life.

Another potential cost of growth is increased stress and reduced leisure. Higher output may be associated with longer working hours or more intense work patterns. While incomes may rise, individuals may experience reduced work-life balance, which is not captured in GDP figures.

Economic Growth and Sustainability

The evaluation of economic growth increasingly focuses on whether growth is sustainable. Sustainable growth refers to growth that meets present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

Sustainability depends on how growth is achieved. Growth driven by improvements in productivity, education, and technology may be more sustainable than growth driven by resource depletion or environmental damage. The composition of growth therefore matters as much as its rate.

Governments may attempt to promote sustainable growth by encouraging cleaner technologies, investing in renewable energy, and improving resource efficiency. Such measures aim to decouple economic growth from environmental harm, allowing output to rise without proportional increases in resource use.

Economic Growth as a Policy Trade-Off

The costs and benefits of economic growth highlight the trade-offs faced by policymakers. Policies that maximise short-run growth may increase environmental damage or inequality. Policies that prioritise environmental protection or redistribution may slow measured GDP growth in the short run.

As a result, economic growth must be considered alongside other objectives such as equity, sustainability, and quality of life. GDP growth alone does not provide a complete measure of economic success, even though it remains a central indicator of economic performance.