Macroeconomics Chapter 5: Policy Objectives - Development

This chapter explores the policy objective of economic development, and the relationship between economic growth and development.

Defining Development

Development refers to a process through which real living standards improve for the population of a country. It is concerned not simply with how much output an economy produces, but with whether people are able to benefit from that production in ways that improve their lives. Development therefore involves changes in economic, social, and institutional conditions that allow people to escape poverty and enjoy better standards of health, education, nutrition, and general well-being.

It is tempting to equate development directly with economic growth. Economic growth refers to an increase in a country’s productive capacity and is usually measured by the rate of growth of real GDP or real GNI. Growth is clearly important because without an expansion of output and income, there are limited resources available to improve living standards. However, development cannot be reduced to growth alone. Economic growth may be necessary for development, but it is not sufficient.

One reason growth alone is insufficient is that additional resources must be used wisely. If output increases but the benefits of that increase are captured by a small proportion of the population, most people may see little or no improvement in their lives. Development therefore requires that growth be of the right kind. It must translate into higher real incomes for large sections of the population and into improved access to essential goods and services. Development is closely linked to the reduction of absolute poverty. A country cannot reasonably be described as developed if a substantial proportion of its population is unable to meet basic needs such as adequate food, shelter, healthcare, and education.

Development also involves structural change within the economy. Over time, the composition of production and employment tends to shift, institutions evolve, and social and political attitudes may change. In some cases, cultural and political structures can either support or hinder development. As a result, development is best understood as a long-term, multidimensional process rather than a single measurable outcome.

The Structure of Economic Activity

An important feature of any economy is the way in which economic activity is organised across different sectors. Economic activity can be classified into primary, secondary, and tertiary production. This classification helps to describe how an economy uses its resources and how its structure changes as development proceeds.

The primary sector involves production that makes direct use of natural resources. This includes agriculture, fishing, forestry, and the extraction of minerals such as coal, oil, and metals. In agriculture, production may include both subsistence farming, where output is consumed by the producer and their household, and commercial farming, where output is sold in markets. The defining characteristic of the primary sector is that production depends directly on the natural environment.

The secondary sector involves the processing and transformation of raw materials into manufactured goods. This includes a wide range of manufacturing activities, from food processing to the production of machinery, vehicles, and construction materials. The secondary sector adds value to primary products by changing their form and often involves the use of capital-intensive production techniques.

The tertiary sector is concerned with the provision of services rather than the production of tangible goods. This sector includes transport, communication, retailing, financial services, education, healthcare, and personal services such as hairdressing. Services support both households and firms by facilitating consumption, production, and exchange.

In some classifications, a further distinction is made within the tertiary sector. Activities based on knowledge, information, and research are sometimes grouped into a quaternary sector. This includes information technology, scientific research, and other information-based services. While useful in some contexts, this distinction does not alter the fundamental role of services within the economy.

Patterns of Sectoral Dependence

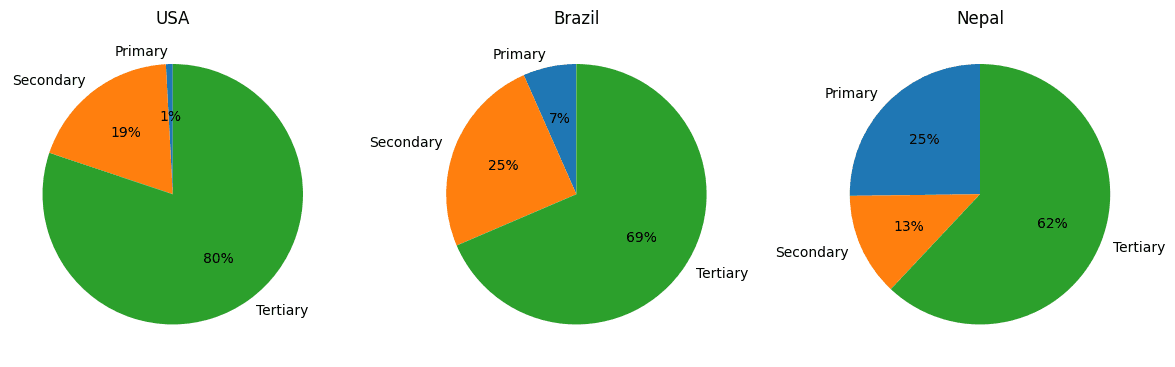

Countries differ markedly in the relative importance of these sectors. In less developed countries, a large proportion of economic activity and employment is typically concentrated in the primary sector, particularly agriculture. In more developed economies, the primary sector accounts for a very small share of total output and employment, while services dominate.

This contrast can be illustrated by comparing economies such as Brazil, Nepal, and the United States. In an economy like the USA, agriculture contributes a very small percentage of GDP, while services account for the majority of economic activity. Manufacturing remains significant but no longer dominates. In Ethiopia, agriculture contributes a much larger share of GDP, and manufacturing plays a relatively limited role.

These differences reflect both the stage of development and differences in productivity across sectors. Labour productivity tends to be lower in agriculture than in manufacturing and services. As a result, economies with a high dependence on agriculture often have lower average incomes. In addition, a large share of agricultural activity in less developed countries may be subsistence production, which is not captured in GDP or GNI statistics because output is consumed directly rather than sold in markets.

The data therefore understate the true importance of agriculture in such economies. The proportion of the labour force engaged in agriculture is often much higher than agriculture’s measured share of output. This reinforces the idea that productivity in the agricultural sector is relatively low.

Implications of Dependence on the Primary Sector

Heavy dependence on agriculture can affect development in several ways. Lower productivity in agriculture limits the scope for rising incomes. There are also fewer opportunities to exploit increasing returns to scale than in manufacturing. As a result, economies that remain heavily reliant on primary production may struggle to generate sustained growth in output per head.

Primary producers may also face difficulties in international markets. Commodity prices tend to be volatile, and agricultural prices have shown a long-run tendency to fall relative to prices of manufactured goods. This means that countries exporting primary products may experience unstable export earnings and declining terms of trade over time. Such conditions can make it harder to finance investment and development.

These structural characteristics help to explain why many less developed countries display similar patterns of economic activity while still facing different development outcomes. Each country has its own configuration of opportunities and constraints, shaped by its resource endowment, institutions, and historical development path.

Identifying Less Developed Countries

There is no single, definitive list of countries that can be classified as less developed countries. The term is used to describe a broad group of economies that share certain characteristics, but these characteristics vary in degree and combination. Less developed countries differ widely in their economic structures, income levels, social outcomes, and development paths. The classification therefore serves as a general descriptive category rather than a precise label.

One feature that is common to many less developed countries is a high dependence on agriculture and other forms of primary production. As discussed earlier, this dependence is associated with lower productivity and lower average incomes. However, reliance on agriculture alone does not fully define whether a country is less developed. Some countries may have significant agricultural sectors but also exhibit higher incomes or strong social outcomes. Conversely, some countries with diversified production structures may still face severe development challenges.

In broad geographical terms, countries commonly described as less developed are concentrated in four main regions. These regions include sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. Even within these regions, there is considerable diversity. Some countries have experienced rapid economic growth and significant improvements in living standards, while others have seen much slower progress. China is often treated separately in development analysis because of its size and its distinctive development path, which differs in important ways from many other countries in East and Southeast Asia.

The absence of a clear boundary between developed and less developed countries highlights the need for careful measurement. Development is a matter of degree rather than a simple either-or classification. To understand where a country stands, economists rely on indicators that attempt to capture different aspects of development.

Indicators of Development

To assess development, it is necessary to compare living standards across countries. A starting point is to examine average income levels. Income provides a rough indication of the resources available to households and governments and therefore of the potential to meet basic needs and improve quality of life.

GNI per Capita

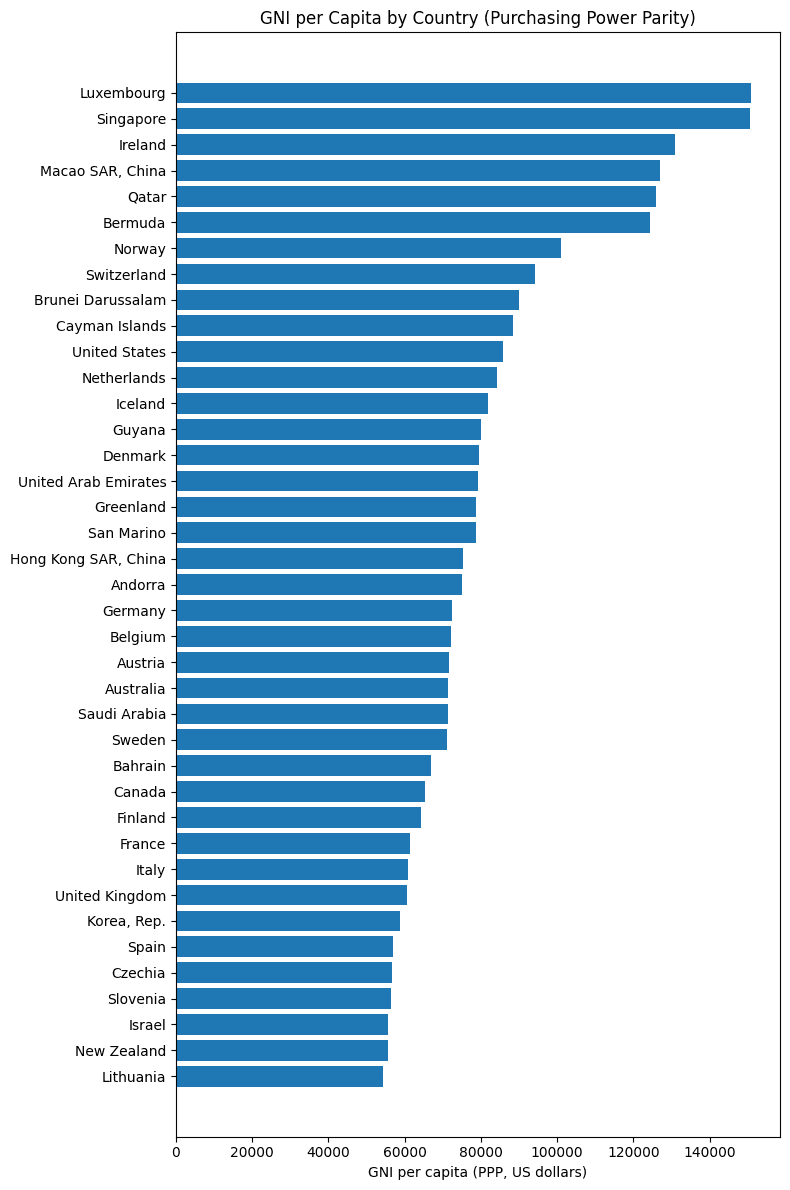

Gross national income per capita is widely used as an indicator of development. GNI measures the total income earned by residents of a country, including income from abroad, and divides this total by the population. GNI per capita therefore represents average income per person.

Using GNI per capita allows economists to compare income levels across countries of very different sizes. A country with a large total income may still have low average incomes if its population is very large. By focusing on income per person, GNI per capita provides a more meaningful comparison of material living standards.

Despite its usefulness, GNI per capita has important limitations. It is an average measure and therefore provides no information about how income is distributed within a country. A high GNI per capita could coexist with extreme inequality, where a small proportion of the population enjoys very high incomes while the majority remains poor. In such cases, average income may give a misleading impression of living standards for most people.

GNI per capita also focuses narrowly on income and does not capture non-monetary aspects of living standards. Access to education, healthcare, clean water, and safe housing all contribute to quality of life but are not directly measured by income figures. For these reasons, GNI per capita is best seen as an initial indicator rather than a complete measure of development.

Exchange Rate Problems

When comparing GNI per capita across countries, incomes are often expressed in a common currency, typically US dollars. This requires converting local currency values using official exchange rates. While this approach allows for straightforward comparison, it introduces several problems.

Official exchange rates may not reflect the true purchasing power of incomes within a country. In many less developed countries, exchange rates are influenced by government intervention. Currencies may be pegged to another currency, such as the US dollar, or deliberately overvalued or undervalued to support specific policy objectives. In such cases, exchange rates reflect government policy rather than relative prices and living standards.

Even where exchange rates are market-determined, they are strongly influenced by prices of internationally traded goods and financial flows. The goods and services consumed by households in less developed countries may differ substantially from those that influence exchange rates. As a result, converting incomes at official exchange rates may misrepresent what people can actually afford in their own countries.

These problems mean that US dollar comparisons of GNI per capita can exaggerate differences in living standards between rich and poor countries. Low-income countries may appear poorer than they really are in terms of the goods and services their residents can purchase locally.

Purchasing Power Parity

To address these issues, economists use purchasing power parity measures. Purchasing power parity exchange rates are designed to reflect the relative purchasing power of incomes across countries. Instead of relying on official exchange rates, PPP rates compare the prices of a broad basket of goods and services in different countries.

GNI per capita measured using PPP therefore provides an estimate of how much people can consume in their own countries, adjusted for differences in price levels. This approach often narrows the apparent gap between high-income and low-income countries compared with US dollar measures.

Although PPP measures improve international comparisons, they are not without limitations. Constructing accurate price comparisons across countries is complex, and consumption patterns vary widely. Nevertheless, PPP-based measures are generally regarded as a more reliable indicator of relative material living standards than measures based on official exchange rates alone.

The Informal Sector and Data Accuracy

Another limitation of income-based measures is their failure to capture informal economic activity. In many less developed countries, a significant proportion of production and employment takes place outside the formal market economy. This includes subsistence agriculture, informal trading, and household production for own consumption.

Such activities often involve no monetary transactions and are therefore excluded from GDP and GNI calculations. As a result, measured income levels may understate the true level of economic activity and consumption in these countries. This is particularly important in rural areas where subsistence farming remains common.

Because GNI is calculated by summing recorded monetary transactions, it cannot capture production that is directly consumed by producers. This further limits its usefulness as a measure of actual living standards in economies where informal activity is widespread.

Income Distribution

GNI per capita also provides no information about income distribution. Two countries with identical average incomes may have very different patterns of inequality. In one country, income may be distributed relatively evenly, while in another it may be concentrated among a small elite.

Data on income distribution reveal that inequality can be extreme in some countries. In certain cases, the poorest segments of the population receive only a tiny share of total income, while the richest groups capture a disproportionately large share. Such inequality has important implications for development because it affects access to education, healthcare, and economic opportunities.

For this reason, income-based indicators must be interpreted with caution. They describe the total resources available in an economy but not how those resources are shared or how they translate into actual living conditions for most people.

Social Indicators and the Limits of Income Measures

The use of income-based measures such as GNI per capita raises a further question. Even if income data are adjusted for purchasing power and interpreted carefully, can income alone be regarded as a reasonable indicator of living standards. Income measures focus on the total resources available in an economy over a given period, calculated from total output, total incomes, or total expenditure. This approach provides information about the scale of economic activity, but it gives only a partial view of how people actually live.

Living standards depend on more than command over goods and services. The quality of people’s lives is shaped by their health, their knowledge, and their ability to make effective use of the resources available to them. Two countries with similar income levels may display very different outcomes in terms of life expectancy, literacy, and access to basic services. These differences arise because societies make different choices about how resources are allocated.

For example, one country may devote a large share of its resources to education and healthcare, while another prioritises military spending or current consumption. In such cases, income per person may be similar, but long-term development outcomes may differ substantially. Over time, societies that invest in education and health may achieve higher productivity and improved living standards, even if short-run income growth is slower.

Environmental conditions also affect quality of life in ways that income measures do not capture. A clean and safe environment contributes directly to well-being. Environmental degradation may reduce quality of life even if measured income rises. In extreme cases, expenditure on cleaning up environmental damage may increase GNI, even though the underlying damage has reduced living standards. This highlights a fundamental weakness of income-based measures when used as indicators of development.

Because of these limitations, economists have developed alternative indicators that attempt to capture a broader concept of development.

The Human Development Index

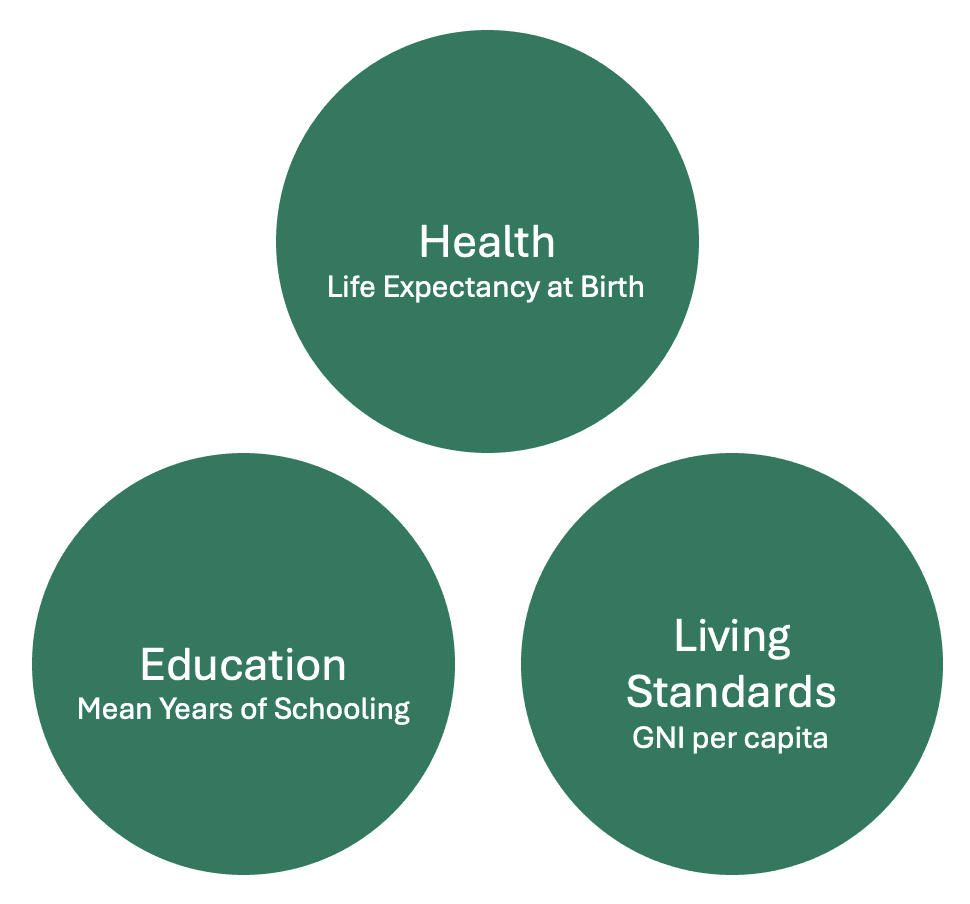

The Human Development Index was introduced to provide a more comprehensive measure of development than income alone. It was developed by the United Nations Development Programme and is designed to reflect key dimensions of human development rather than economic activity as such.

The HDI is based on the idea that development involves three core elements. These are access to resources, knowledge of how to make use of those resources, and the ability to live a long and healthy life. Each of these elements is measured using a specific indicator, and the results are combined into a single composite index.

Access to resources is measured using GNI per capita adjusted for purchasing power parity. This component reflects the extent to which people have command over goods and services. Knowledge is measured using indicators of education. These include mean years of schooling, which measures the average number of years of education received by adults, and expected years of schooling, which estimates the number of years of education a child entering the school system can expect to receive given current enrolment patterns. Health is measured using life expectancy at birth, which reflects overall health conditions and access to healthcare.

Each of these indicators is normalised to produce an index value between zero and one. Higher values indicate better outcomes. The three indices are then combined to produce the HDI, which also ranges between zero and one. Countries with higher HDI values are regarded as having achieved higher levels of human development.

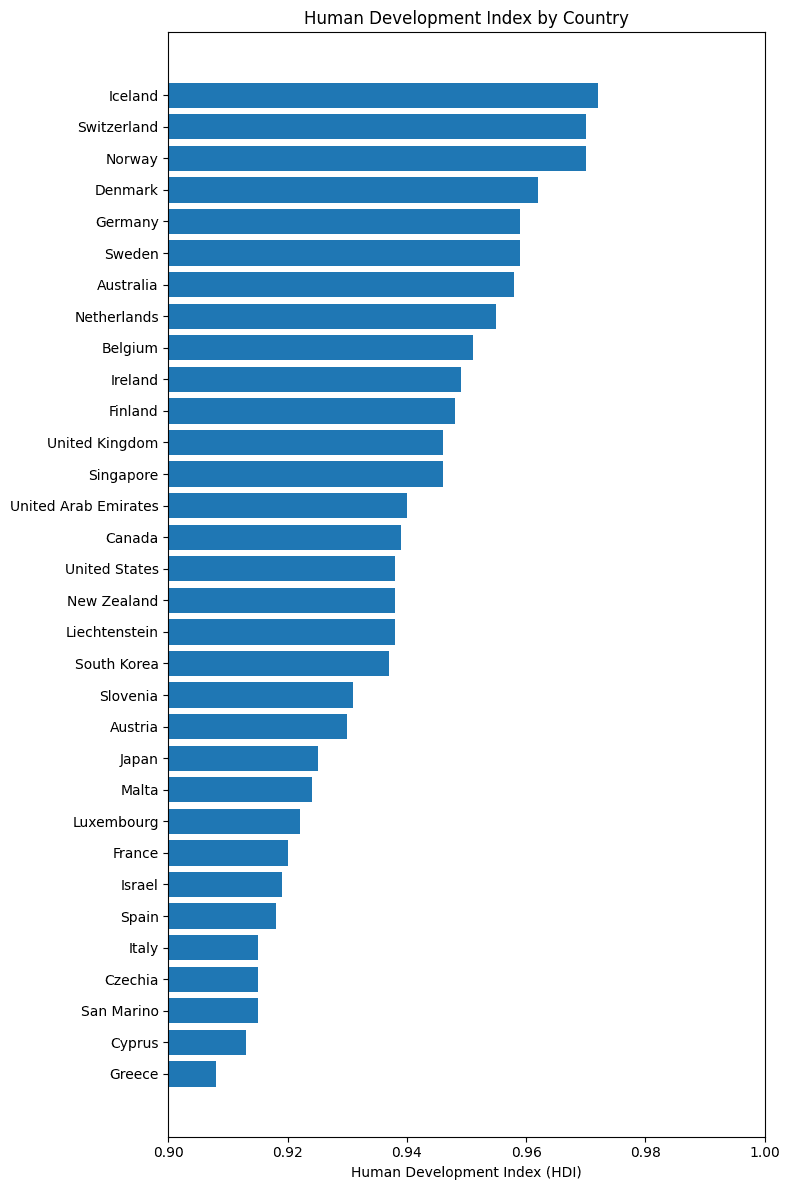

Interpreting the HDI

When HDI values are compared across countries, the gap between high-income and low-income countries often appears smaller than when comparisons are based on GNI per capita alone. This reflects the fact that some countries with relatively low incomes have achieved strong outcomes in education or health. Conversely, some countries with higher incomes perform less well on these social indicators.

For example, a country may have a lower GNI per capita than another but achieve a higher HDI because it has invested heavily in education and healthcare. This suggests that income measures alone may underestimate the level of development achieved in such countries. Similarly, countries with relatively high incomes but poor health or education outcomes may rank lower on the HDI than their income ranking would suggest.

The HDI therefore provides a more balanced picture of development by recognising that growth in income does not automatically translate into improved quality of life. However, the HDI remains a simplified measure. Reducing a complex concept such as development to a single index inevitably involves trade-offs and omissions.

Inequality and Adjustments to the HDI

One important limitation of the HDI is that it is based on average values and therefore does not reflect inequality within countries. High average education or health outcomes may conceal large disparities between different groups in society.

To address this issue, the United Nations has developed the inequality-adjusted Human Development Index. This measure adjusts the HDI to account for inequality in income, education, and health. The adjustment reflects the loss in potential human development that arises from unequal distribution of these outcomes.

In countries with high levels of inequality, the inequality-adjusted HDI can be significantly lower than the unadjusted HDI. This indicates that although average outcomes may appear strong, large segments of the population are unable to benefit fully from development. In contrast, countries with more equal distributions tend to show smaller differences between the two measures.

Gender inequality also plays an important role in shaping development outcomes. In many countries, women face disadvantages in access to education, healthcare, and employment. These disparities reduce overall human development by limiting the potential of a large share of the population. Measures that compare male and female HDI values highlight the extent to which gender inequality affects development.

Other Indicators of Development

Although the HDI captures key dimensions of development, it does not include every aspect that may be important. Development is influenced by many factors, and different indicators may be useful for understanding specific problems faced by particular countries.

Access to infrastructure such as electricity, clean water, sanitation, transport, and communication networks provides important information about living conditions and development constraints. High infant mortality rates indicate problems in healthcare and nutrition. Levels of unemployment and underemployment provide insight into labour market conditions. Patterns of economic activity, such as heavy dependence on low-productivity agriculture, may signal structural barriers to development.

These indicators help to build a fuller picture of development by revealing the specific challenges faced by different economies. They also underline the fact that development paths differ across countries. There is no single route to development, and countries face different configurations of opportunities and constraints.

Sustainable Development

Development is not only concerned with improving living standards today but also with ensuring that these improvements can be maintained over time. This concern leads to the concept of sustainable development. Sustainable development refers to development that meets the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

Living standards in advanced economies have risen dramatically over recent decades, and many developing countries are now seeking to follow a similar path. In some cases, they have achieved rapid economic growth and significant reductions in poverty. This raises a fundamental question. Can this process continue indefinitely, or are there limits imposed by the environment and the availability of natural resources.

Economic growth has clear environmental consequences. As output expands, firms require more inputs, many of which are derived from the natural environment. Production also generates waste and pollution. These effects mean that growth can impose costs on society that are not captured by conventional measures of output and income. Concerns about pollution, resource depletion, and climate change have led to doubts about whether continued growth is compatible with long-run development.

The idea of sustainable development emerged in response to these concerns. It emphasises that development must take account of environmental constraints and ensure that economic progress does not undermine future living standards.

Functions of the Environment

One way of understanding the relationship between the economy and the environment is to view the environment as performing several essential economic functions. The environment is not simply a passive backdrop to economic activity. It plays an active role in supporting production and consumption.

The environment provides resources that are used as inputs into production. Firms require energy and raw materials in order to produce goods and services. These resources may be renewable, such as wind or solar energy, or non-renewable, such as coal, oil, and mineral deposits. The availability of these resources places limits on the scale and type of economic activity that can take place.

The environment also provides amenities that contribute directly to people’s quality of life. Clean air, natural landscapes, and recreational spaces generate utility for households. Enjoyment of these amenities improves well-being even though it may not involve market transactions. The loss or degradation of environmental amenities therefore represents a real reduction in living standards, even if it is not reflected in income measures.

A third function of the environment is to act as an absorber of waste. Both firms and households generate waste as a result of production and consumption. This waste must be absorbed by the environment in some form. The capacity of the environment to absorb waste without damage is limited. When this capacity is exceeded, pollution accumulates and environmental quality deteriorates.

These three functions are closely linked. Using resources and generating waste can reduce the availability of amenities. For example, industrial pollution may damage ecosystems and reduce the enjoyment people derive from natural environments. Sustainable development requires that these interactions be managed in a way that preserves environmental capacity over time.

Sustainability and Environmental Capital

A key issue in sustainable development is whether the environment can continue to perform its functions indefinitely. This depends on how environmental capital is managed. Environmental capital refers to the stock of natural resources and environmental systems that support economic activity and human well-being.

One approach to sustainability argues that the stock of environmental capital should not decline over time. Under this view, development is sustainable if future generations inherit an environment that allows them to enjoy at least the same quality of life as the current generation. This requires careful management of resource use, conservation of ecosystems, and control of pollution.

Questions arise about the extent to which natural resources can be substituted by other forms of capital. In some cases, technological progress allows economies to use resources more efficiently or to replace non-renewable resources with renewable alternatives. In other cases, environmental damage may be irreversible. Loss of biodiversity or severe climate change may impose long-term costs that cannot easily be offset by higher incomes or technological advances.

Sustainable development therefore involves difficult trade-offs. Slowing economic growth in the short run may be necessary to protect environmental resources in the long run. This can be politically and socially challenging, especially in countries where large sections of the population still live in poverty.

Sustainable Development and Economic Growth

The relationship between economic growth and sustainable development is complex. On one hand, growth provides the resources needed to reduce poverty, improve education and health, and invest in cleaner technologies. On the other hand, rapid growth can intensify environmental damage if it relies on polluting energy sources and resource-intensive production methods.

The experience of rapidly growing economies illustrates these tensions. Industrialisation requires reliable energy supplies, and in many cases this has involved heavy reliance on fossil fuels. This has contributed to rising emissions of carbon dioxide and other pollutants. In some economies, emissions have increased rapidly even as living standards have improved.

The case of China illustrates this dilemma. Rapid economic growth has lifted millions of people out of poverty, but it has also been associated with sharply rising carbon emissions. While emissions in some advanced economies have stabilised, emissions in fast-growing developing economies have increased as energy demand has expanded. This reflects the use of coal and other fossil fuels to support industrialisation and urbanisation.

China has recognised the environmental challenges associated with its growth model and has taken steps to reduce reliance on coal and invest in renewable energy. However, the scale of its economy and population means that environmental pressures remain significant. The example highlights the difficulty of balancing growth and environmental protection in practice.

The underlying issue is that expanding productive capacity, often described as shifting the long-run aggregate supply curve to the right, does not automatically lead to sustainable development. Growth that damages environmental capital may raise income in the short run while reducing quality of life in the long run. Sustainable development requires that growth be managed in a way that takes environmental constraints seriously.

Global Dimensions of Sustainable Development

Sustainable development also has an international dimension. Environmental problems such as climate change and ocean pollution cross national boundaries. Actions taken in one country can impose costs on others. This raises issues of fairness and responsibility, particularly between developed and developing countries.

Developing countries argue that advanced economies achieved high living standards while generating significant environmental damage and that it is unfair to restrict growth in poorer countries. At the same time, unchecked growth in emerging economies risks severe global environmental consequences. Reconciling these perspectives is one of the central challenges of sustainable development.

In 2015, the member states of the United Nations adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. This agenda recognises that ending poverty and improving living standards must go hand in hand with protecting the environment. It emphasises the need to improve health and education, reduce inequality, promote economic growth, and address climate change while preserving natural resources.

Sustainable development therefore represents an attempt to integrate economic, social, and environmental objectives. It acknowledges that development is not simply about increasing output, but about improving human well-being in a way that can be sustained over time.