Macroeconomics Chapter 6: Policy Objectives - Employment

This chapter explores the concept of employment and the policy objective of full employment.

Introduction to Employment and Unemployment

Employment occupies a central position in macroeconomic analysis because it determines how fully an economy is using one of its key factors of production, namely labour. When a large proportion of the working-age population is in employment, the economy is closer to operating at its productive capacity. When unemployment is high, this indicates that labour resources are underutilised and that potential output is not being achieved. For this reason, employment is closely linked to other macroeconomic objectives such as economic growth, price stability, and living standards.

Full employment is widely regarded as a desirable macroeconomic objective. An economy with high levels of employment is producing more output than an economy with idle labour resources, and this higher level of output can translate into higher incomes and improved living standards. At the same time, employment matters not only from the perspective of aggregate output, but also from the perspective of individuals. Paid work provides income, but it also contributes to social inclusion, self-worth, and economic security. Persistent unemployment therefore represents both an economic inefficiency and a social problem.

However, it is important to recognise from the outset that unemployment will never be completely eliminated in a modern economy. Even when the economy is performing well, there will always be some workers who are between jobs, searching for better opportunities, or adjusting to changes in the structure of production. Labour markets are dynamic rather than static. Firms expand and contract, industries grow and decline, and workers move in response to changes in wages, working conditions, and skill requirements. As a result, the presence of some unemployment is not necessarily a sign of economic failure.

The existence of unemployment does not automatically imply that the economy is operating below full capacity. Some unemployment reflects normal turnover in the labour market and may even be associated with improved efficiency, as workers move into jobs that better match their skills. The key issue for policymakers is therefore not whether unemployment exists, but what type of unemployment exists, how large it is, and whether it reflects temporary adjustment or more serious underlying problems.

This chapter explores the nature of employment and unemployment in detail. It examines how employment is defined, how the workforce is structured, and how unemployment is measured. It also considers the policy objective of full employment, the different causes of unemployment, and the consequences that unemployment has for individuals, firms, and the wider economy. By doing so, it provides a framework for understanding why employment is such an important indicator of economic performance and why achieving high levels of employment remains a central concern of macroeconomic policy.

Employment and the Workforce

To understand employment and unemployment clearly, it is necessary to begin with the structure of the working-age population and the categories into which people are classified. In the US context, the working-age population is traditionally defined as those aged between 14 and 67, although changes in retirement patterns mean that this age range is no longer an exact guide to who is economically active. Within this population, people are divided into three main groups, namely the employed, the unemployed, and the economically inactive.

People who are in employment are those who are working for firms or other organisations, such as government bodies, as well as those who are self-employed. Employment therefore includes both wage and salary earners and individuals who work for themselves. From the perspective of production, those in employment are contributing labour as a factor of production and are therefore directly involved in generating output in the economy.

The unemployed are those who are part of the workforce but do not currently have a job. Being unemployed does not simply mean being out of work. To be classified as unemployed, individuals must be economically active. This means that they must be without a job, but available for work and actively seeking employment. People who are not looking for work, even if they do not have a job, are not counted as unemployed.

The economically inactive are those of working age who are neither employed nor unemployed. This group includes people who are not looking for work for a variety of reasons. Students who are in full-time education and not seeking employment fall into this category. So do people who have retired early, those who are unable to work due to illness or disability, and those who are caring for family members. Also included are discouraged workers. Discouraged workers are individuals who would like to work but have given up searching for a job because they believe that no suitable employment is available. Although they are without work, they are not counted as unemployed because they are not actively seeking employment.

The distinction between these categories is crucial because unemployment is defined relative to the workforce, not the total population. The workforce consists of all those who are economically active, meaning those who are either in employment or unemployed. People who are economically inactive are not part of the workforce and therefore do not enter unemployment statistics.

This distinction explains why changes in unemployment figures do not always reflect changes in the number of people without jobs. For example, if a discouraged worker begins actively looking for work, they move from being economically inactive to being unemployed. This increases the measured unemployment level even though the number of people without jobs has not changed. Conversely, if unemployed workers stop searching for work, unemployment may fall even though employment has not increased.

Employment levels are an important indicator of economic performance because they show how much labour the economy is using in the production process. In the US, employment has increased substantially over time. The total number of people in employment rose significantly from the early 1980s through to the late 2010s, despite periods of recession and economic slowdown. This long-run increase reflects population growth, rising labour force participation, and structural changes in the economy.

Although employment fell during periods of recession, such as the financial crisis at the end of the 2000s, it recovered relatively quickly in subsequent years. By the late 2010s, the number of people in employment had risen above its pre-crisis level. This suggests that, over time, the US labour market has shown a degree of flexibility in responding to economic shocks.

An important feature of employment trends in the US has been the growth of part-time work. The number of part-time workers has increased both in absolute terms and as a proportion of total employment. This reflects changes in the structure of the economy, particularly the growth of service industries, as well as changes in working patterns and preferences. Part-time employment may offer flexibility for some workers, but it also raises questions about job security, income stability, and underemployment, issues that will be explored later in the chapter.

Understanding the structure of the workforce and how employment is defined is essential before moving on to unemployment itself. Without clear definitions, it is easy to misinterpret labour market data and draw incorrect conclusions about economic performance. The next step is to consider the concept of full employment and why it has become a central objective of macroeconomic policy.

Full Employment as a Policy Objective

Full employment is regarded as one of the central objectives of macroeconomic policy because it reflects how effectively an economy is using its available labour resources. When employment is high, more workers are contributing to production, output is closer to its potential level, and living standards are higher than they would otherwise be. Conversely, when unemployment is widespread, the economy is failing to make full use of labour as a factor of production, resulting in lost output and lower incomes.

Full employment refers to a situation in which all people who are economically active and willing and able to work at the going wage rate are able to find employment. This definition immediately makes clear that full employment does not mean that everyone has a job. Some people are not part of the workforce because they are economically inactive, and others may be unemployed for short periods as they move between jobs. These individuals are not excluded from the concept of full employment.

A common misunderstanding is that full employment implies zero unemployment. In practice, this is neither realistic nor desirable. In a dynamic economy, there will always be some workers changing jobs, entering the labour market for the first time, or searching for work that better matches their skills. This type of unemployment arises even when the economy is performing well and reflects the normal functioning of the labour market rather than a lack of demand for labour.

Even when the economy is operating close to full capacity, there may also be short periods when people are between jobs or engaged in job search. As a result, unemployment will never fall to zero. For this reason, full employment is better understood as the absence of cyclical or demand-deficient unemployment rather than the complete elimination of all unemployment.

From a macroeconomic perspective, full employment is closely linked to the concept of productive capacity. When the economy is at full employment, it is operating at its full employment level of real output. This corresponds to a situation in which labour and other resources are being used as efficiently as possible, given existing technology and institutions. In such a situation, output cannot be increased further without putting upward pressure on costs and prices.

This link between full employment and productive capacity has important implications for price stability. If the economy is operating very close to full employment, firms may find it increasingly difficult to recruit additional workers. Labour shortages can put upward pressure on wages as firms compete for workers. Higher wages may then feed through into higher costs of production and rising prices. In this way, there may be a conflict between achieving full employment and maintaining stable inflation.

For this reason, some economists argue that full employment should be defined as the level of unemployment at which there is no tendency for inflation to accelerate. Under this view, full employment corresponds to a rate of unemployment that is consistent with stable prices rather than zero unemployment. The precise unemployment rate that meets this condition is difficult to identify and may vary over time and between countries, depending on factors such as labour market flexibility and institutional arrangements.

Another difficulty with the concept of full employment is that it cannot be observed directly. Policymakers must rely on indicators such as unemployment rates, vacancy data, and wage growth to judge whether the economy is close to full employment. These indicators can give conflicting signals, making it hard to determine whether unemployment reflects normal labour market turnover or deeper structural problems.

Despite these difficulties, full employment remains an important policy objective because of the high costs associated with unemployment. High unemployment represents a waste of resources and reduces the economy’s ability to produce goods and services. It also imposes significant social costs on individuals and communities. As a result, governments continue to place a high priority on policies that support employment, even though the precise definition of full employment remains contested.

Measuring Unemployment

Measuring unemployment accurately is more complex than it might first appear. Over time, different methods have been used to quantify unemployment, and each method reflects particular assumptions about who should be counted as unemployed. In the UK, the measurement of unemployment has been especially contentious, with changes in definitions and approaches leading to debate about how well official statistics capture the true state of the labour market.

However, measures based on benefit claims do not provide a comprehensive measure of unemployment. In the United States, unemployment insurance claims record the number of people who are receiving unemployment benefits, but this figure does not correspond directly to the total number of unemployed individuals. Eligibility for unemployment insurance is limited. Some unemployed people are not entitled to benefits because they have insufficient recent work history, are self-employed, or have exhausted their entitlement. Others may be eligible but choose not to apply for benefits. These individuals are unemployed in an economic sense but are not captured by claims-based data.

At the same time, claims-based measures may include some individuals who are not genuinely unemployed. People may continue to receive unemployment benefits while not actively seeking work or while being unwilling to accept available jobs at the prevailing wage. Although claimants are required to meet job-search conditions, enforcement is imperfect. As a result, unemployment insurance claims can both understate the true level of unemployment and misrepresent the degree of labour market slack.

Because of these limitations, unemployment insurance claims are not regarded as a reliable measure of unemployment. They can provide useful information about short-term changes in job losses and labour market conditions, particularly during economic downturns, but they do not accurately measure how many people are without work and actively seeking employment.

For official purposes, unemployment in the United States is measured using the unemployment rate produced by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. This measure is based on the Current Population Survey, a large monthly household survey. The survey classifies individuals as employed, unemployed, or economically inactive based on their responses to standardised questions about work, job search, and availability for employment. This approach measures unemployment directly rather than inferring it from benefit claims and allows for consistent comparison over time and across countries.

Under the ILO definition, unemployed people are those who are without a job, available to start work, and actively seeking employment. This definition also includes individuals who are out of work but have already found a job and are waiting to start it within the next two weeks. By focusing on job search and availability rather than benefit status, the ILO definition aims to capture unemployment more accurately.

The ILO unemployment rate is calculated as the percentage of the workforce that is unemployed. The workforce consists of all economically active individuals, meaning those who are either employed or unemployed. Economically inactive people are excluded from both the numerator and the denominator of the unemployment rate. This approach avoids many of the distortions associated with benefit-based measures, since it does not depend on eligibility rules or claiming behaviour.

However, even the ILO measure is not without limitations. It relies on survey data rather than a complete census of the population. As a result, the figures are subject to sampling error and depend on the accuracy of respondents’ answers. Despite these limitations, the ILO unemployment rate is generally regarded as the most appropriate measure of unemployment for economic analysis.

Understanding how unemployment is measured is essential for interpreting labour market data. Different measures can tell very different stories about the state of the economy. The next step is to consider the specific problems that arise when attempting to measure unemployment accurately, and why even the ILO measure may fail to capture the full extent of labour market underutilisation.

Problems of Measuring Unemployment

Even when unemployment is measured using widely accepted definitions, significant problems remain. These problems arise because unemployment is a complex economic and social phenomenon that cannot be captured perfectly by any single statistical measure. As a result, official unemployment figures in the United States must always be interpreted with caution.

One major difficulty is that unemployment statistics depend on how individuals classify their own activities. Under the definition used by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, people are counted as unemployed only if they are without a job, available to work, and actively seeking employment. This definition excludes individuals who would like to work but are not currently searching for a job. Discouraged workers fall into this category. These individuals may have become pessimistic about their job prospects after repeated failures to find employment. Although they are without work and would accept a job if offered, they are not counted as unemployed because they are not actively seeking work. As a result, official unemployment figures may understate the true degree of labour market slack in the economy.

Another problem is that unemployment data do not capture underemployment. Underemployment occurs when individuals are employed but are not working as many hours as they would like or are employed in jobs that do not fully use their skills. For example, a highly educated worker employed in a low-skilled, part-time position is classified as employed, even though their productive potential is not being fully utilised. Underemployment represents a form of labour market inefficiency that is not reflected in the headline unemployment rate.

The growth of part-time, temporary, and gig-based employment in the United States has increased the importance of underemployment as an issue. Some workers may accept part-time or short-term jobs because full-time employment is unavailable. In these cases, employment levels may rise while labour market conditions remain weak for many workers. As a result, falling unemployment rates do not necessarily indicate an improvement in job quality or income stability.

Measurement problems are especially pronounced when unemployment statistics are used to compare conditions across countries, but they also exist within the United States. Although informal employment is less widespread than in many developing economies, some economic activity still takes place outside formal employment arrangements. This includes informal self-employment, casual work, and unreported income-generating activities. Such work may not be fully captured by official surveys, leading to an incomplete picture of labour market conditions.

Another limitation arises from the use of sample surveys such as the Current Population Survey. Although this survey is designed to be representative of the US population, it relies on a relatively small sample compared with the total population. Sampling error can therefore affect the accuracy of the results, particularly for smaller demographic groups or geographic areas. Changes in survey design or question wording can also affect measured unemployment rates, making comparisons over time more difficult.

In addition, unemployment figures provide only a snapshot of labour market conditions at a particular moment. They do not show how long individuals remain unemployed. Long-term unemployment is generally more damaging than short-term unemployment because workers’ skills may deteriorate and their attachment to the labour market may weaken over time. Two economies with the same unemployment rate may therefore face very different challenges if one has a high proportion of long-term unemployed workers and the other does not.

Because of these limitations, unemployment statistics must be interpreted alongside other indicators of labour market performance. These include employment-to-population ratios, labour force participation rates, job vacancy data, hours worked, and wage growth. Only by examining a range of indicators can economists gain a fuller understanding of labour market conditions and the extent to which labour resources are being underutilised in the US economy.

Calculating the Unemployment Rate

The unemployment rate is one of the most widely used indicators of labour market conditions. To interpret it correctly, it is essential to understand precisely how it is calculated and what it represents. The unemployment rate does not measure the proportion of the total population that is unemployed. Instead, it measures the proportion of the active workforce that is without a job but seeking work.

The active workforce consists of all individuals who are economically active. This includes those who are in employment and those who are unemployed. Economically inactive individuals, such as students who are not seeking work, early retirees, and discouraged workers, are excluded from the workforce and therefore do not enter the calculation.

The unemployment rate is calculated by dividing the number of unemployed people by the total workforce and expressing the result as a percentage. This definition highlights why changes in the unemployment rate can sometimes be misleading. The rate can change not only because the number of unemployed people changes, but also because the size of the workforce changes.

For example, if employment remains constant but more people enter the workforce and fail to find jobs, unemployment will rise and the unemployment rate will increase. Conversely, if unemployed individuals leave the workforce by becoming economically inactive, the unemployment rate may fall even though employment has not increased. This is why unemployment data must be interpreted in conjunction with information about labour force participation.

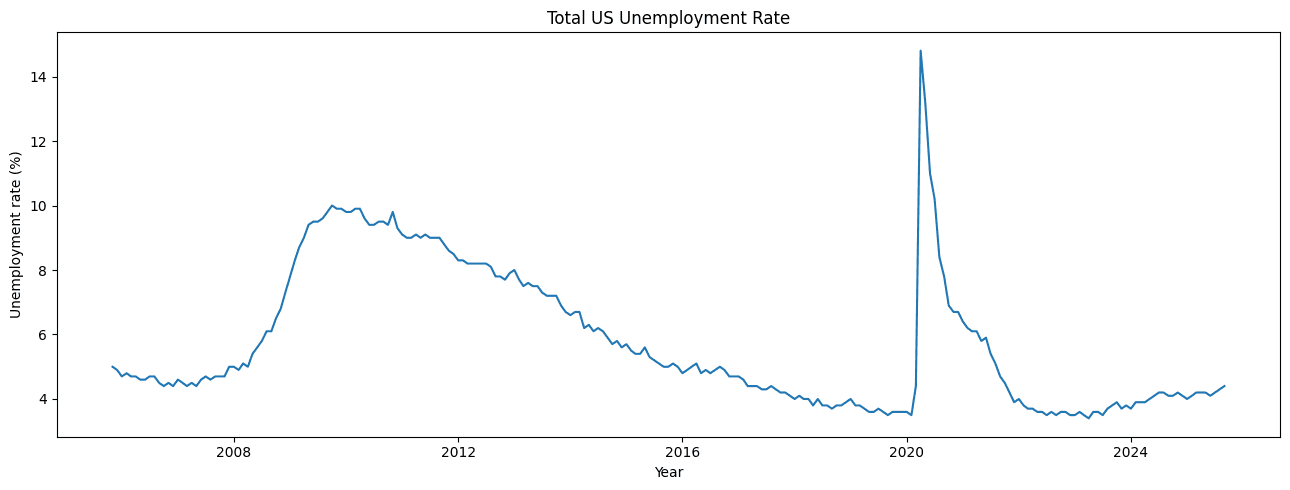

Over the long run, unemployment rates in the US have fluctuated in response to changes in economic conditions. Periods of recession are typically associated with rising unemployment as firms reduce output and cut back on labour demand. During economic expansions, unemployment tends to fall as firms increase production and hire more workers.

The unemployment rate therefore moves in a cyclical pattern, rising during downturns and falling during recoveries. However, the level around which it fluctuates may change over time. Structural changes in the economy, such as shifts in industrial composition or changes in labour market institutions, can affect the average rate of unemployment.

It is also important to consider the distribution of unemployment across different groups. Unemployment rates may differ by age, gender, region, and skill level. For example, young people often experience higher unemployment rates than older workers because they have less experience and are more likely to be entering the labour market for the first time. Regional differences in unemployment may reflect variations in industrial structure and local economic conditions.

Despite its limitations, the unemployment rate remains a valuable indicator because it provides a concise summary of labour market conditions. When used alongside other data, it helps policymakers and economists assess the extent to which labour resources are being used and whether the economy is operating close to full employment.

Causes of Unemployment

Unemployment can arise for a variety of reasons, and understanding these causes is essential for analysing labour market performance and designing appropriate policy responses. Different types of unemployment reflect different underlying mechanisms. Some forms of unemployment are temporary and unavoidable in a dynamic economy, while others are more persistent and reflect deeper structural problems. Distinguishing between these causes helps explain why unemployment exists even during periods of economic growth and why reducing unemployment can be difficult.

Frictional Unemployment

Frictional unemployment arises because workers and jobs are not perfectly matched at every moment in time. In any economy, there is constant movement of people between jobs. Workers leave employment for many reasons, such as seeking better pay, improved working conditions, or opportunities that better match their skills. At the same time, new workers enter the labour market after completing education or training. During the period when individuals are searching for work or moving between jobs, they are counted as unemployed.

This type of unemployment is an inevitable consequence of labour market turnover. Even when the economy is growing and firms are expanding employment, some workers will be between jobs. Frictional unemployment therefore exists even when there is no shortage of job vacancies overall. It reflects the time required for job search and matching rather than a lack of labour demand.

Frictional unemployment may actually be beneficial to the economy. When workers are able to search for jobs that suit their skills and preferences, the allocation of labour improves. Over time, this can raise productivity as workers move into roles where they are more effective. An economy with very low frictional unemployment might indicate limited mobility or barriers to job search, which could reduce efficiency.

The level of frictional unemployment depends on factors such as the availability of information about job vacancies, the efficiency of employment agencies, and the willingness of workers to move between regions or occupations. Improvements in information technology and online job platforms can reduce the time workers spend searching for employment, thereby lowering frictional unemployment.

Structural Unemployment

Structural unemployment occurs when there is a mismatch between the skills and location of workers and the requirements of available jobs. This type of unemployment arises from changes in the structure of the economy. As industries expand and contract over time, the demand for certain types of labour increases while demand for others declines. Workers who possess skills that are no longer in demand may find it difficult to obtain employment, even if there are job vacancies elsewhere in the economy.

Structural unemployment is often associated with long-term changes such as shifts from manufacturing to services or from primary production to more capital- and skill-intensive industries. For example, if an economy experiences a decline in heavy industry and growth in high-technology services, workers with skills specific to declining industries may struggle to find new employment without retraining.

Geographical immobility can exacerbate structural unemployment. Jobs may be created in regions that are different from those where unemployed workers live. If workers are unwilling or unable to move, unemployment may persist in some areas even while other regions experience labour shortages. High housing costs, social ties, and lack of information can all limit geographical mobility.

Structural unemployment tends to be more persistent than frictional unemployment. Because it reflects a mismatch between labour supply and labour demand, it cannot be resolved simply by an increase in aggregate demand. Addressing structural unemployment often requires policies that focus on education, training, and mobility rather than short-term demand management.

Technological Unemployment

Technological unemployment arises when technological change reduces the demand for certain types of labour. Advances in technology can increase productivity by allowing firms to produce the same level of output with fewer workers. While technological progress can raise living standards in the long run, it can also lead to job losses in specific occupations or industries.

Automation, mechanisation, and the use of computer-based systems have replaced labour in a wide range of activities. Workers whose tasks can be performed more cheaply or efficiently by machines may find their jobs eliminated. If these workers do not have the skills required for new types of employment, they may become unemployed.

Technological unemployment is closely related to structural unemployment, but it is driven specifically by changes in production methods rather than shifts in consumer demand. Over time, new technologies may also create new jobs, but the skills required for these jobs may differ from those lost. This creates a transitional problem for workers who are displaced by technological change.

The impact of technological unemployment depends on the pace of technological progress and the ability of the education and training system to equip workers with relevant skills. Rapid technological change can increase the risk of long-term unemployment for some groups if retraining opportunities are limited.

Geographical Unemployment

Geographical unemployment arises when unemployed workers are located in areas where there are few job opportunities, while vacancies exist elsewhere. This form of unemployment reflects regional imbalances in economic activity. Some regions may experience industrial decline, while others benefit from growth in new industries.

Geographical unemployment may persist if workers are unable or unwilling to relocate. Barriers to mobility include high costs of moving, lack of affordable housing in growing regions, and social factors such as family ties. Transport infrastructure and access to information about job opportunities can also affect mobility.

Although geographical unemployment is sometimes treated as a separate category, it overlaps with structural unemployment. In both cases, the problem is a mismatch between the characteristics of the labour force and the location or nature of available jobs. Reducing geographical unemployment often requires policies that encourage regional development, improve infrastructure, or support labour mobility.

Cyclical and Demand-Deficient Unemployment

Cyclical unemployment, also known as demand-deficient unemployment, is unemployment that arises because of fluctuations in the level of economic activity over the business cycle. This type of unemployment is closely linked to changes in aggregate demand and is therefore strongly influenced by macroeconomic conditions. When aggregate demand falls, firms experience a decline in sales and revenues. In response, they reduce output. As output falls, the demand for labour also falls, leading to job losses and rising unemployment.

Cyclical unemployment typically increases during periods of recession. A recession is characterised by falling or slow growth in real output, often accompanied by declining consumer spending, reduced investment by firms, and lower exports. When firms face weaker demand for their goods and services, they have little incentive to maintain previous levels of employment. Workers may be laid off, working hours may be reduced, or new hiring may be postponed. As a result, unemployment rises even though workers may be willing and able to work at the prevailing wage rate.

This form of unemployment is fundamentally different from frictional or structural unemployment. It does not arise because workers lack the right skills or are searching between jobs. Instead, it reflects a deficiency of demand in the economy as a whole. Workers are unemployed because firms do not require their labour, not because there is a mismatch between workers and jobs. For this reason, cyclical unemployment is often regarded as the most serious form of unemployment from a macroeconomic perspective.

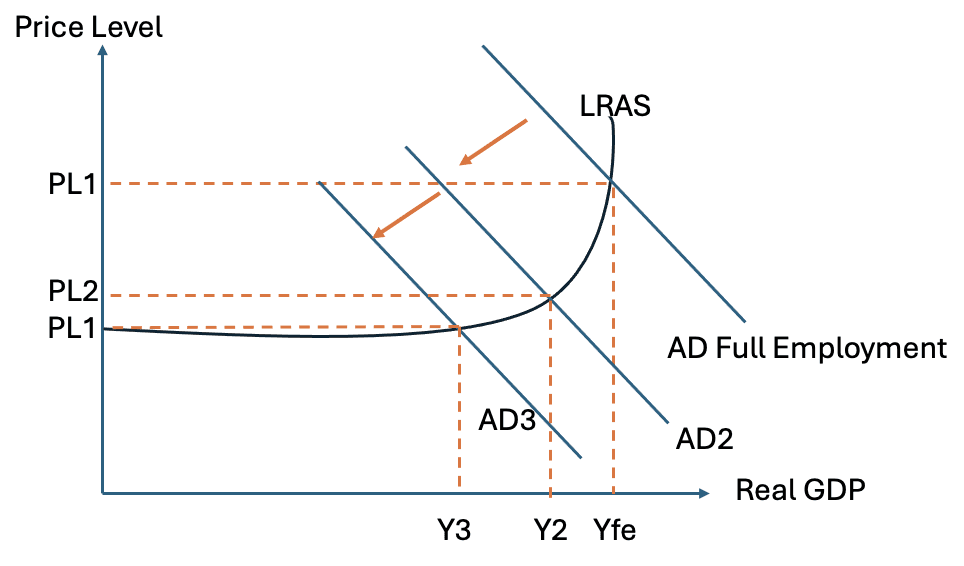

Cyclical unemployment can be illustrated using a diagram showing aggregate demand and aggregate supply. When aggregate demand is insufficient to generate full employment output, the economy operates below its productive capacity. The level of real output is lower than the full employment level of output, and this shortfall is referred to as a negative output gap. At this level of output, the demand for labour is lower than the supply of labour, resulting in unemployment. This unemployment is demand-deficient because it is caused by insufficient spending in the economy.

As the economy moves through the economic cycle, cyclical unemployment tends to fluctuate. During periods of economic expansion, rising demand leads firms to increase production and hire more workers. Unemployment falls as job opportunities expand. During economic downturns, the opposite occurs. Demand weakens, output contracts, and unemployment rises. This pattern explains why unemployment rates often move in the opposite direction to economic growth.

The severity of cyclical unemployment depends on the depth and duration of economic downturns. A mild slowdown may lead to only a small increase in unemployment, while a deep and prolonged recession can result in large-scale job losses and persistent unemployment. If demand remains weak for an extended period, cyclical unemployment may turn into long-term unemployment, with workers finding it increasingly difficult to re-enter the labour market.

Cyclical unemployment is particularly important because, in principle, it can be reduced through macroeconomic policy. Policies designed to stimulate aggregate demand, such as expansionary fiscal policy or monetary policy, can increase spending in the economy. Higher demand encourages firms to expand output and employment, reducing demand-deficient unemployment. For this reason, governments often focus on stabilising demand during recessions to prevent sharp rises in unemployment.

However, managing demand is not straightforward. Expansionary policies may take time to have an effect, and there may be trade-offs with other objectives such as price stability. If demand is stimulated too strongly when the economy is already close to full employment, inflationary pressures may emerge. This highlights the difficulty of balancing the objectives of low unemployment and stable prices.

Cyclical unemployment therefore plays a central role in macroeconomic analysis. It links unemployment directly to movements in aggregate demand and output and helps explain why unemployment rises during recessions even when labour markets function normally in other respects.

Seasonal Unemployment

Seasonal unemployment arises because the demand for labour in certain industries varies predictably over the course of the year. This type of unemployment is linked to seasonal patterns in production and consumption rather than to changes in the overall level of economic activity. As a result, seasonal unemployment occurs even when the economy is otherwise stable and growing.

Some industries face fluctuations in demand that are closely tied to the seasons. Agriculture provides a clear example. The demand for labour rises during planting and harvesting periods but falls during other parts of the year. Workers employed on farms may therefore experience periods of unemployment once seasonal work has been completed. Similarly, industries linked to tourism often experience strong demand during peak holiday seasons and much weaker demand during off-peak periods. Hotels, restaurants, and leisure services may hire large numbers of workers during busy periods and release them when demand falls.

Construction is another industry where seasonal factors can affect employment. Weather conditions influence the feasibility of outdoor work. In colder or wetter months, construction activity may slow down, leading to reduced demand for labour. As conditions improve, employment in the sector may rise again. These patterns are regular and predictable rather than random.

Seasonal unemployment differs from cyclical unemployment because it is not caused by fluctuations in aggregate demand across the whole economy. Even if overall demand is strong, employment in seasonal industries will still rise and fall according to the time of year. It also differs from structural unemployment because workers’ skills may still be appropriate for the jobs they hold, but those jobs are not available year-round.

Because seasonal unemployment follows a regular pattern, it can often be anticipated by workers and firms. Some workers accept seasonal employment with the expectation that they will be unemployed for part of the year or will move between different types of work. For example, a worker may combine employment in tourism during the summer with other forms of work during the winter months. In this sense, seasonal unemployment may be less damaging than other forms of unemployment, as it is expected and temporary.

From a statistical perspective, seasonal unemployment can complicate the interpretation of labour market data. Unemployment figures may rise or fall at certain times of the year due to seasonal factors rather than changes in underlying economic conditions. To address this problem, unemployment data are often seasonally adjusted. Seasonal adjustment involves removing predictable seasonal patterns from the data to reveal underlying trends. This allows economists and policymakers to distinguish between temporary seasonal movements and more fundamental changes in labour market conditions.

Despite this adjustment, seasonal unemployment remains an important feature of the labour market in some industries. It highlights the fact that not all unemployment is a sign of economic weakness. Some forms of unemployment arise from the way production is organised and the natural constraints faced by particular sectors.

Wage Inflexibility and Unemployment

Wage inflexibility refers to a situation in which real wages do not adjust freely in response to changes in supply and demand in the labour market. When wages are inflexible, they may remain above the level that would clear the labour market, leading to persistent unemployment. This explanation of unemployment is particularly associated with Keynesian analysis and focuses on imperfections in labour market adjustment rather than on voluntary choice or short-term fluctuations.

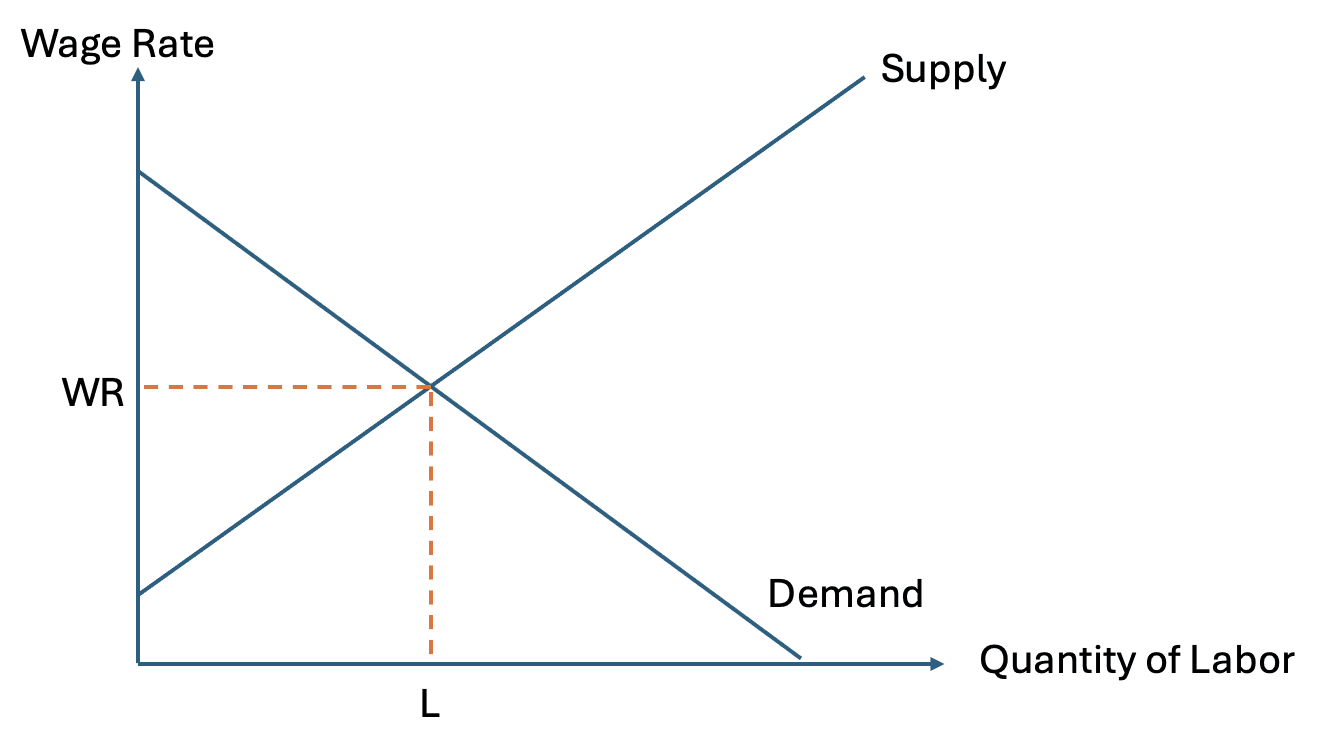

To understand how wage inflexibility can cause unemployment, it is useful to consider the labour market in terms of labour demand and labour supply. Firms demand labour because workers contribute to production. The demand for labour is derived from the demand for the goods and services that firms produce. When demand for output rises, firms increase production and require more workers. When demand for output falls, the demand for labour decreases. As a result, the labour demand curve slopes downward, reflecting the fact that firms are willing to employ more workers at lower real wages.

Labour supply reflects the willingness of workers to offer their labour at different real wage rates. As real wages rise, work becomes more attractive relative to leisure, and more individuals are willing to supply their labour. This gives the labour supply curve an upward slope. In a perfectly flexible labour market, the real wage would adjust to equate labour demand and labour supply, resulting in an equilibrium level of employment.

At the equilibrium real wage, the quantity of labour demanded equals the quantity of labour supplied. All workers who are willing to work at this wage are able to find employment, and there is no involuntary unemployment. Any worker who is not employed at this wage is choosing not to work, rather than being unable to find a job.

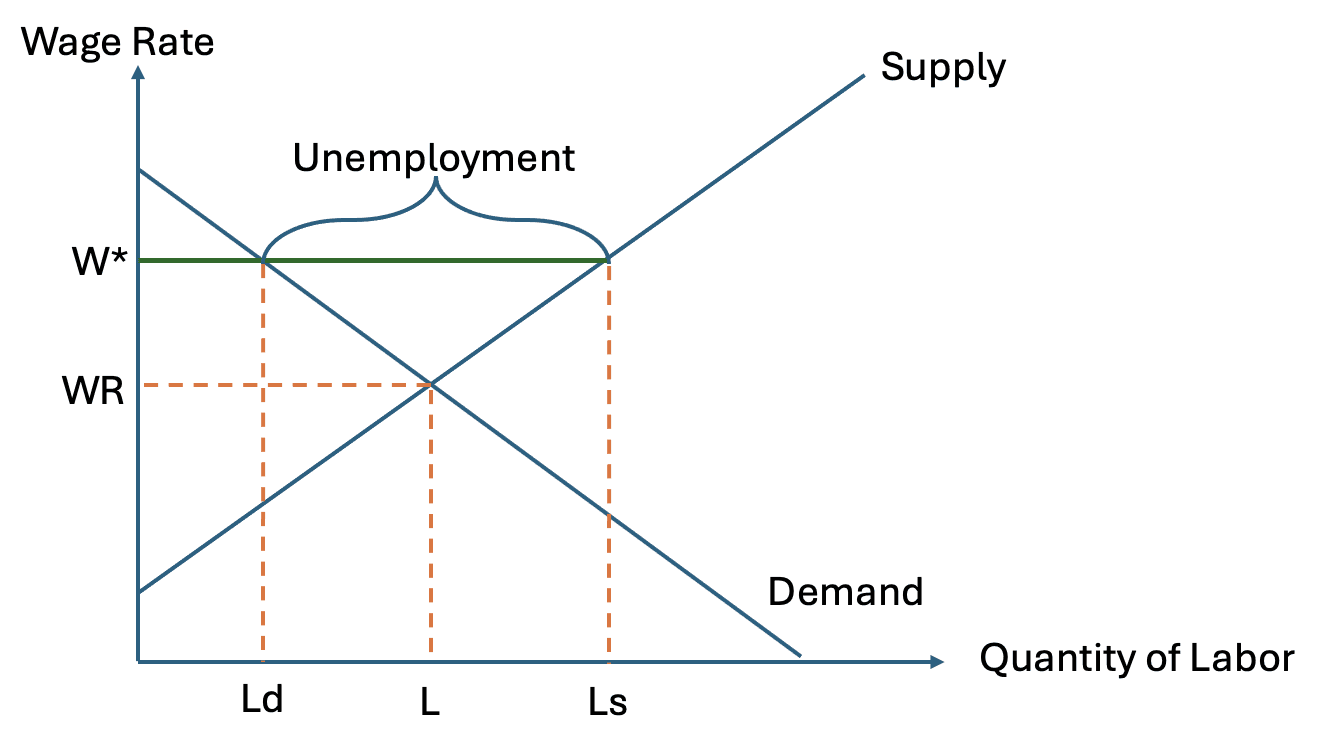

However, in practice, real wages may be inflexible downward. This means that wages do not fall even when there is excess supply of labour. If the real wage is set above the equilibrium level, the quantity of labour supplied exceeds the quantity of labour demanded. Firms are unwilling to employ all workers who wish to work at this wage, resulting in unemployment. This unemployment is involuntary because workers are willing to work at the prevailing real wage but cannot find jobs.

Several factors can contribute to wage inflexibility. Trade unions may negotiate wage rates that are higher than the equilibrium level in order to protect their members’ incomes. Minimum wage legislation can also prevent wages from falling below a certain level, even if labour demand is weak. Long-term employment contracts and efficiency wage considerations may further limit firms’ willingness or ability to cut wages. Firms may fear that wage reductions will reduce worker morale, effort, or productivity, making them reluctant to lower wages even in the face of high unemployment.

From a Keynesian perspective, wage inflexibility plays a key role in explaining persistent unemployment. If wages do not adjust downward when demand for labour falls, the labour market does not clear. Unemployment persists because the real wage remains too high relative to labour demand. In this framework, unemployment is not the result of workers choosing leisure over work, but of rigidities that prevent wages from adjusting to restore equilibrium.

This analysis has important policy implications. If unemployment is caused by insufficient demand for labour combined with wage rigidity, policies that stimulate aggregate demand may be more effective than policies aimed at reducing wages. Increasing demand for goods and services raises firms’ demand for labour, shifting the labour demand curve to the right and increasing employment at the existing real wage. In contrast, attempts to reduce wages may face resistance and may have negative effects on income and consumption.

Wage inflexibility therefore provides a powerful explanation of why unemployment can persist even when workers are willing to work and firms could profitably employ them at lower wages. It highlights the role of institutions and behavioural factors in shaping labour market outcomes and reinforces the idea that unemployment cannot always be explained by voluntary choice or short-term adjustment.

Voluntary Unemployment

Voluntary unemployment refers to a situation in which individuals choose not to accept available work at the prevailing wage rate. In this case, unemployment arises not because jobs are unavailable, but because workers decide that the wages or conditions offered are not acceptable relative to their preferences. From an economic perspective, voluntary unemployment reflects individual choice rather than a failure of the labour market to provide employment.

The concept of voluntary unemployment is closely linked to the idea of a reservation wage. The reservation wage is the minimum real wage at which an individual is willing to supply their labour. If the market wage is below this level, the individual may prefer not to work, choosing leisure or other non-market activities instead. When many workers have reservation wages above the prevailing wage, voluntary unemployment may occur.

Voluntary unemployment can also be influenced by the availability of income from sources other than employment. Unemployment benefits, savings, or support from family members may reduce the immediate financial pressure to accept a job. This can allow individuals to remain unemployed while they search for better employment opportunities. In such cases, unemployment may be temporary and associated with job search rather than long-term detachment from the labour market.

It is important to distinguish between voluntary unemployment from the individual’s perspective and from the social perspective. An individual may rationally choose not to accept a particular job because it offers low pay, poor working conditions, or limited prospects. However, from the perspective of the economy as a whole, this individual is still an unused labour resource. Whether unemployment is voluntary or involuntary does not change the fact that output is lower than it could be if more people were employed.

Migration and Unemployment

Migration has become an increasingly important factor shaping labour markets, and its relationship with unemployment is often the subject of debate. Migration refers to the movement of people from one country to another, usually in search of better employment opportunities, higher wages, or improved living conditions. From an economic perspective, migration affects the labour market by altering the supply of labour and, potentially, the demand for labour as well.

When migrants enter a country, they increase the size of the labour force. This raises labour supply, which may put downward pressure on wages or increase competition for jobs, particularly in the short run. For this reason, migration is sometimes associated with fears that unemployment will rise among existing workers. However, this outcome is not inevitable and depends on the characteristics of migrants and the structure of the economy.

A key issue is whether migrant labour is a substitute for, or a complement to, domestic labour. If migrants possess skills that are similar to those of existing workers, they may compete for the same jobs. In this case, increased labour supply could increase unemployment or reduce wages for some groups of workers, particularly in low-skilled occupations. The impact is likely to be strongest in local labour markets where migrants are concentrated.

However, migrants may also complement domestic labour rather than replace it. If migrants fill jobs that domestic workers are unwilling or unable to do, or if they possess skills that are in short supply, they can increase overall productive capacity without displacing existing workers. For example, migrants may work in sectors experiencing labour shortages, allowing firms to expand output. In this case, migration can reduce bottlenecks in the labour market and support higher levels of employment.

Migration can also affect labour demand. Migrants are not only workers but also consumers. As the population increases, demand for goods and services rises, which can lead firms to expand production and hire more workers. This increase in labour demand may offset, or even exceed, the initial increase in labour supply, limiting any rise in unemployment.

The impact of migration on unemployment therefore depends on the balance between these effects. Empirical evidence suggests that, in many cases, the overall impact of migration on unemployment is small. While some groups of workers may face increased competition, the economy as a whole may benefit from a larger and more flexible labour force.

Migration can also influence unemployment over the longer term by affecting economic growth. By increasing the size of the workforce and contributing skills and human capital, migration can raise potential output. Higher potential output allows the economy to grow without generating inflationary pressure, which can support higher levels of employment.

From a policy perspective, the relationship between migration and unemployment is complex. Restricting migration may reduce labour supply in the short run, but it may also limit economic growth and exacerbate labour shortages in key sectors. Conversely, encouraging migration without adequate support for integration and training may create localised pressures in the labour market.

Migration therefore plays an important role in shaping employment outcomes. Its effects on unemployment cannot be understood simply in terms of increased labour supply. Instead, they depend on how migrants interact with existing workers, how firms respond, and how the economy adjusts over time.

Consequences of Unemployment

Unemployment has wide-ranging consequences that extend beyond the immediate loss of income experienced by those without work. These consequences affect individuals, families, firms, governments, and the economy as a whole. Because of these effects, unemployment is regarded as one of the most serious macroeconomic problems, even when it arises from temporary or cyclical factors.

For individuals, unemployment results in a direct loss of income. Without earnings from employment, households may struggle to meet basic needs such as housing, food, and energy costs. Although unemployment benefits may provide some financial support, they typically replace only a portion of previous earnings. As a result, unemployed individuals often experience a significant fall in living standards.

Beyond the financial impact, unemployment can have serious social and psychological effects. Work provides structure, routine, and a sense of purpose. Prolonged unemployment can lead to loss of confidence, reduced self-esteem, and increased stress. In some cases, it may contribute to mental health problems such as anxiety and depression. These effects can persist even after individuals return to work, particularly if unemployment has been long-term.

Unemployment can also affect families and communities. Financial pressure may place strain on relationships within households. In areas where unemployment is concentrated, social problems such as crime and social exclusion may become more prevalent. Communities that experience long-term unemployment may suffer from declining public services and reduced investment, reinforcing cycles of deprivation.

From the perspective of firms, high unemployment may appear beneficial in the short run because it increases the pool of available labour and may reduce upward pressure on wages. However, widespread unemployment can also reduce demand for firms’ products. Unemployed individuals have lower incomes and therefore spend less, reducing sales and profits. This can discourage investment and slow economic growth, ultimately harming firms themselves.

Unemployment also imposes significant costs on government. As unemployment rises, government spending on unemployment benefits and other forms of income support increases. At the same time, tax revenues fall because fewer people are earning income and paying income tax. This combination of higher spending and lower revenue worsens the government’s fiscal position and may lead to larger budget deficits.

The economy as a whole suffers from unemployment because it represents a waste of resources. Labour is a key factor of production, and when workers are unemployed, the economy is producing below its potential level of output. This lost output is an opportunity cost. Goods and services that could have been produced are never made, and the economy’s long-term productive capacity may be damaged if workers’ skills deteriorate during prolonged periods of unemployment.

Unemployment can also have multiplier effects. A fall in employment reduces household income and consumption, which in turn reduces firms’ revenues and may lead to further job losses. This process can amplify the initial increase in unemployment and contribute to deeper and more prolonged downturns in economic activity.

The persistence of unemployment can lead to hysteresis effects, where high unemployment in one period increases the likelihood of high unemployment in the future. Long-term unemployed workers may lose skills or become less attractive to employers, making it harder for them to find jobs even when economic conditions improve. This can raise the natural level of unemployment and make it more difficult to achieve full employment.

Because of these wide-ranging consequences, reducing unemployment is a key objective of economic policy. Governments aim not only to minimise the level of unemployment but also to prevent temporary downturns from causing lasting damage to individuals and the economy.

The Effects of Full Employment

Full employment has important implications for the performance of the economy and for living standards. When the economy is operating close to full employment, labour resources are being used efficiently, and output is closer to its potential level. This has clear benefits, but it can also create challenges for policymakers, particularly in relation to inflation and wage pressure.

One of the main benefits of full employment is higher real output. With more people in work, the economy produces a greater quantity of goods and services. This increases national income and raises average living standards. Higher employment also supports stronger tax revenues, allowing governments to fund public services such as education, healthcare, and infrastructure without relying excessively on borrowing.

Full employment also tends to improve income security for households. When job opportunities are plentiful, workers face a lower risk of prolonged unemployment. This can increase consumer confidence and encourage higher levels of spending. Strong consumer demand, in turn, supports business revenues and investment, reinforcing economic growth.

From a social perspective, full employment reduces many of the problems associated with unemployment. Lower unemployment means fewer individuals experience the loss of income, social exclusion, and psychological stress associated with being out of work. Communities with high employment levels tend to experience lower levels of poverty and social tension.

However, operating close to full employment can also generate pressures in the labour market. When unemployment is low, firms may find it difficult to recruit workers. Labour shortages can lead to upward pressure on wages as firms compete to attract and retain employees. Rising wages increase firms’ costs of production and may lead to higher prices for goods and services.

These inflationary pressures highlight a potential trade-off between full employment and price stability. If demand in the economy continues to rise when output is already close to its full employment level, inflation may accelerate. For this reason, policymakers must balance the goal of full employment with the need to maintain stable prices.

Another issue is that very low unemployment may reduce labour market flexibility. When workers are confident that they can easily find alternative employment, they may be less willing to accept certain jobs or working conditions. While this can improve job quality, it may also increase recruitment difficulties for firms, particularly in lower-paid or less attractive occupations.

Assessing whether full employment has been achieved is inherently difficult. As discussed earlier, some unemployment will always exist due to frictional and structural factors. Policymakers must therefore judge whether the level of unemployment reflects normal labour market turnover or whether it indicates excess demand pressures that could lead to inflation.

Despite these challenges, full employment remains a central objective of economic policy. The benefits of high employment in terms of output, income, and social well-being are substantial. At the same time, maintaining full employment requires careful management of aggregate demand and close monitoring of labour market conditions to avoid destabilising inflation.